1449: The Hall was erected as part of the original College, now known as Old Court.

1449: The Hall was erected as part of the original College, now known as Old Court.

1531–2: Linenfold panelling erected (removed 1732–4, re-erected in the Servants’ Hall of the President’s Lodge, transferred 1896/97 to the President’s Study).

1548: Screens passage created between the external doors of the hall. By implication, the passage might have created a gallery above.

1640: Date of an inventory and assembly instructions for a demountable stage used for drama performances in the Hall. The Hall had been used for performances of drama from much earlier (as required by the Statutes of 1559): the practice ceased sometime during the Commonwealth period.

1655: Date on the dinner bell in the bell tower on the roof over the Hall, also inscribed “WB”.

1685: “…ye bow-window in ye Hall repair’d with Freestone & new glass there…” [Magnum Journale, vol. 6, f. 221, 1685 September]

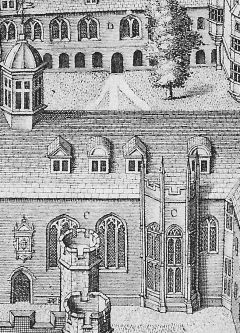

1690: Loggan’s view (which was probably drawn 1685–7) shows dormer windows over the Hall, indicating that there might already have been attics and a flat ceiling inserted over the Hall. It also shows an additional window looking over the High Table (northern) end of the Hall: this window must have been removed at or before the installation of classical panelling of 1732–4. The other two side windows and the oriel window are shown with tracery, which had disappeared by the time of the 1815 view below. This Loggan view shows the new cupola for the Hall bell made in 1685.

1690: Loggan’s view (which was probably drawn 1685–7) shows dormer windows over the Hall, indicating that there might already have been attics and a flat ceiling inserted over the Hall. It also shows an additional window looking over the High Table (northern) end of the Hall: this window must have been removed at or before the installation of classical panelling of 1732–4. The other two side windows and the oriel window are shown with tracery, which had disappeared by the time of the 1815 view below. This Loggan view shows the new cupola for the Hall bell made in 1685.

1732–4: The Hall was fitted up in its present neat and elegant manner

[Plumptre MS] (that is to say, in a classical style). If not already present, a flat ceiling was inserted just below the main cross-beams of the roof structure, and an Italian cornice added. The present classical-style panelling was erected. The architect was Sir James Burrough, the joinery was by James Essex the Elder (father of the James Essex who built the bridge and Essex Building), carving by Woodward, and the wrought iron gates to the Screens were by Jonas Jackson (the Jacksons were a Cambridge family of gatesmiths). In the gallery, a single central entrance door replaced two earlier doors on either side: these, now blocked, survive as cupboards on the south side of the wall.

1742: It was reported that the Hall:

... very lately was elegantly fitted up according to ye present tast and is now by much ye neatest Hall of any in ye University being completely wainscoted and painted wth handsom fluted Pillars behind ye Fellows Table at ye upper end of it over wch are neatly carved ye arms of ye Foundress: at ye lower end of it over ye two neat Iron Doors of ye Screens wch front ye Butteries and Kitchin is a small Gallery for Musick occasionally.

[Cole MSS, 22 Feb 1742]

1766: The three portraits over High Table were given, one by each of the three sons of Harry, 4th Earl of Stamford. They (family name Grey) were descendants of Elizabeth Woodville by her first marriage to John Grey of Groby. The portraits, copies by Thomas Hudson, from left to right are of:

- Erasmus, visiting scholar (the portrait), given by the second son, Booth Grey, at Queens’ 1758–61;

- Elizabeth Woodville, second foundress queen (the portrait), given by the eldest son, George Harry Grey, Fellow-Commoner 1755–58;

- Sir Thomas Smith, statesman (the portrait), given by the third son, John Grey, Fellow-Commoner 1761–63.

The portrait of Elizabeth Woodville is a three-quarter length copy of one of the half-length portraits of her at Queens’. The portrait of Sir Thomas Smith appears to be a copy of the one at Saffron Walden Town Council offices.

1774: A College Order directing “to Scrape and paint a Stone Colour all the Stone window Frames in the First Court” [Conclusion Book 1774 July 5] is indicative of the period when the dictates of fashion might have led to the removal of tracery from the windows of the Hall.

1780: Doors to the Hall were added behind the iron gates of the Screens.

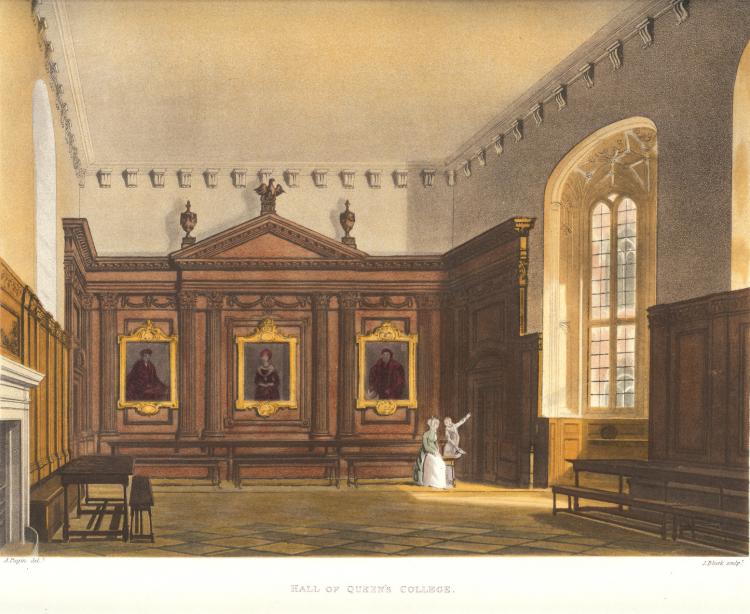

1815: Print published by Ackermann of the Hall interior. The side windows are of reduced height compared with the present. The oriel window is shown here without tracery, and without stained glass.

1815: Print published by Ackermann of the Hall interior. The side windows are of reduced height compared with the present. The oriel window is shown here without tracery, and without stained glass.

Drawn by Auguste-Charles Pugin, aquatint engraving by John Bluck. Published in A History of the University of Cambridge, its Colleges, Halls, and Public Buildings by William Combe, published by R. Ackermann in 1815.

In common with many other prints of this period, the apparent grandeur of the surroundings has been emphasised by unnaturally shrinking the size of people depicted within. In reality, the eyes of an adult on the dais would be level with the lower edge of the portraits.

1819–22: Stained glass by Charles Muss inserted in the oriel and side windows (removed, sometime before 1854, possibly 1846, mostly transferred to the Long Gallery and to the Audit Dining Room). The glass was paid for out of a gift of 50 guineas from Isaac Milner in 1819, and benefactions from Philip, Earl of Hardwicke; George-Harry, Earl of Stamford; Sir Henry Russel, Bart.; George Henry Law, D.D., Bishop of Chester; Henry Godfrey, D.D., President of this College; and many Members of this Society

[Commemoration of Benefactors 1823, p. 17n]. The arms of some of the benefactors were included in the glass. The total cost of the glass was £454 10s 0d [AHUC, Vol. 2, p. 47n].

That the Earl of Hardwicke, Sir Henry Russel, & the Earl of Stamford having presented to the College their armorial Bearings in painted Glass, the Master do express the respectful acknowledjment of the Society of the Same.

[Conclusion Book, 1820 November 9]

Agreed that the Master be requested to allow his Armorial Bearings to be placed in the window of the Hall at the expense of the Society.

[Conclusion Book, 1821 April 26. There was no record of the Master’s reply, and it is not known what the arms of Henry Godfrey were.]

Agreed & Ordered that the Oriel Window in the Hall be completed by Mr Muss according to his Plan.

[Conclusion Book, 1822 June 7]

This is also the likely period when embattled parapets (removed 1909) were added to the Old Court elevation of the Hall.

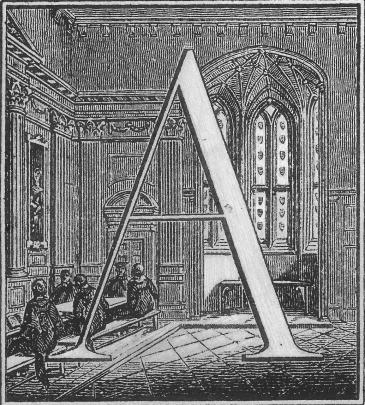

1822: This is an enlargement of a decorated initial capital used in several books printed in the 19th century concerning Queens’ College. It was first used in a collection of the Statutes of Queens’ College by G.C. Gorham, Fellow, printed in 1822. Gorham wrote:

1822: This is an enlargement of a decorated initial capital used in several books printed in the 19th century concerning Queens’ College. It was first used in a collection of the Statutes of Queens’ College by G.C. Gorham, Fellow, printed in 1822. Gorham wrote:

The initial letters were drawn by myself on wood, and engraved over my drawings by Hughes. For the subjects of these illustrations, see the published Catalogue of Queen’s Coll. Library, Pref.

[A Bibliographical Catalogue of Books Privately Printed, by John Martin, 1834, p201]

The stained glass coats of arms were inserted into the oriel window 1819–22, so this view can be accurately dated.

In this view, it appears that a class is being held on High Table.

1829: The present and former pupils of Joshua King (then Tutor, later President 1832–57), subscribed 300 guineas to having a full-length portrait of King painted by William Beechey, to be erected in the college Hall [Cambridge Chronicle, No. 3503, 1829 Dec 11, p. 2]. The portrait was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1830 [The Royal Academy of Arts : A Complete Dictionary of Contributors … , by Algernon Graves, 1905, Vol. 1, p. 164]. In 1831, Thomas Goff Lupton engraved a mezzotint of the portrait, of which the caption read:

Painted by Sir Wm. Beechey R.A.

Engraved by Thomas Lupton.

JOSHUA KING, A.M.

FRAS; FRSL; FGS; FCPS.

Fellow and Tutor of Queen’s College, Cambridge.

From the original Painting in the Hall of Queen’s College.

Presented by the former & present Pupils of Mr. King, as a mark of their esteem & attachment.

Published by Henry Leggatt & Co. 85, Cornhill, July 1831.

At some later date, the original full-length portrait was cut down to head-and-shoulders, and is now in the President’s Lodge.

1836: This is the date enscribed on the decorative chimney stacks above the fireplace of the Hall.

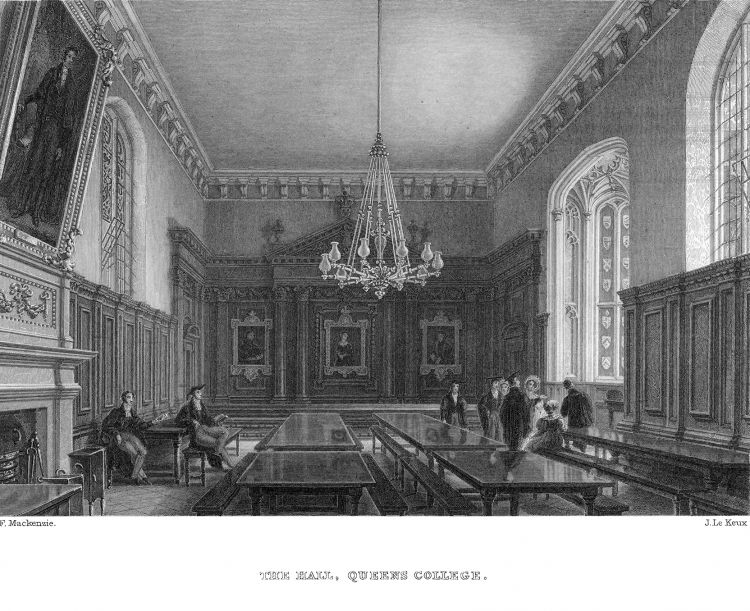

1842: Print by Le Keux of the Hall interior. By comparison with the Ackermann print of 1815, the following changes can be seen:

1842: Print by Le Keux of the Hall interior. By comparison with the Ackermann print of 1815, the following changes can be seen:

- The stained glass of 1819–22 can be seen in the windows, which remain without tracery.

- The 1830 portrait of Joshua King has appeared over the fireplace.

- A gas chandelier has appeared (ca. 1835?).

Drawn by F. Mackenzie. Engraved by John Le Keux. Published in Memorials of Cambridge in part form 1837–1842 by Thomas Wright and Harry Longueville Jones. Revised edition of Memorials of Cambridge by C.H. Cooper published 1860.

This print clearly shows that, in the blind light of the oriel window, internal tracery survived, when the tracery was removed from the main lights during the 18th century. This internal tracery appears compatible with the oriel tracery visible in the 1690 Loggan view.

1845: Tastes were changing, away from the neo-classical ones of the previous century:

Considerable restorations are contemplated in both the hall and the chapel of Queen’s College. It was but recently discovered how much mischief the paganizing mania of the last century had inflicted on these two venerable edifices. The roof of the hall proves to be the finest in the University, of beautiful high pitched open timbers, now underdrawn and totally concealed by a flat plaister ceiling. Considerable remains of the internal panelling still exist in the president's lodge.

[The Ecclesiologist, Vol. 4 (n.s. 1), No. 39 (n.s. 3), 1845 May, p. 142]

1846: The flat ceiling was removed, and the roof restored. The architect was said [AHUC, Vol. 2, p. 47] to have been simply “Mr Dawkes”: there is no record in the college accounts of the name of the architect. The only likely candidate seems to have been Samuel Whitfield Daukes. At this stage, the roof was undecorated. Daukes put up a new dinner bell tower, and also created a louvre in the roof, which was an inappropriate act of restoration (the hall always had a fireplace, so would never have needed a louvre: the louvre was removed again circa 1951). Tracery, also to the design of Daukes, was inserted in the then plain mullioned windows (tracery later replaced in 1857 in the case of the side windows): possibly the installation of this 1846 tracery caused the removal of the stained glass of 1819–22. Judging by appearances, Daukes seems to have taken the pre-existing tracery in the blind lights of the oriel window as the model for the restored tracery. Photographs [here, here] show a similar scheme scaled up for the side windows.

1846: The flat ceiling was removed, and the roof restored. The architect was said [AHUC, Vol. 2, p. 47] to have been simply “Mr Dawkes”: there is no record in the college accounts of the name of the architect. The only likely candidate seems to have been Samuel Whitfield Daukes. At this stage, the roof was undecorated. Daukes put up a new dinner bell tower, and also created a louvre in the roof, which was an inappropriate act of restoration (the hall always had a fireplace, so would never have needed a louvre: the louvre was removed again circa 1951). Tracery, also to the design of Daukes, was inserted in the then plain mullioned windows (tracery later replaced in 1857 in the case of the side windows): possibly the installation of this 1846 tracery caused the removal of the stained glass of 1819–22. Judging by appearances, Daukes seems to have taken the pre-existing tracery in the blind lights of the oriel window as the model for the restored tracery. Photographs [here, here] show a similar scheme scaled up for the side windows.

Agreed to present the thanks of the Society to Mr. Moon for his handsome donation towards the ornamental repairs of the hall.

[College Order, 1847 January 14]

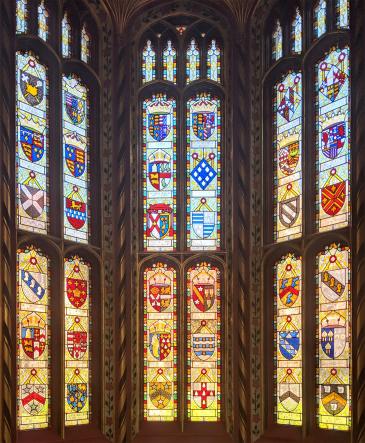

1854: The Oriel Window had the present stained glass inserted by Hardman of Birmingham, depicting the armorial bearings of the foundresses, early benefactors, and the Presidents from Andrew Dokett to Isaac Milner. (The earlier glass by Muss 1819–22, if it had not already been moved, was removed to the President’s Lodge). The new glass was ordered September 1854 [Hardman Glass Order Book 1852–6, 1854 Sep 3] and paid for March 1855 [QC Accounts 1855/6, Hall Restoration Account, f. 54].

1854: The Oriel Window had the present stained glass inserted by Hardman of Birmingham, depicting the armorial bearings of the foundresses, early benefactors, and the Presidents from Andrew Dokett to Isaac Milner. (The earlier glass by Muss 1819–22, if it had not already been moved, was removed to the President’s Lodge). The new glass was ordered September 1854 [Hardman Glass Order Book 1852–6, 1854 Sep 3] and paid for March 1855 [QC Accounts 1855/6, Hall Restoration Account, f. 54].

Agreed that the thanks of the Society be presented to Mr Moon for his liberality in restoring the bay-window of our Hall, and in filling the same with stained glass.

[College Order, 1854 November 15]

Top row: left: the Boar’s Head and the Arms of the College; centre: the two foundress Queens; right: the two principal benefactrices.

Row 2: Four early benefactors, and the fathers of Anne Neville and Elizabeth Woodville.

Rows 3–6: All the Presidents from Andrew Dokett to Isaac Milner, omitting the Presidents during the commonwealth period, between the two presidencies of Edward Martin. The arms shown for the 4th President, Robert Bekinshaw, are incorrect, and appear to be those of Grey/Booth, representing the 5th Earl of Stamford, a benefactor of the 1760s. The arms shown for the 6th President, Thomas Farman, are incorrect, and appear to be the arms of the 4th President, Robert Bekinshaw. These mistakes seems to have been inherited from the earlier glass of 1819–22, now in the oriel window of the Long Gallery.

For a key to the arms, see Old Hall glass.

1857/8: The side windows were raised to their present height, and new tracery installed, to the design of John Johnson, architect, replacing the 1846 tracery by Daukes. It is likely that this period was also when the roof eaves on the west (Cloister Court) side were converted to embattled parapets, which were removed again in 1909.

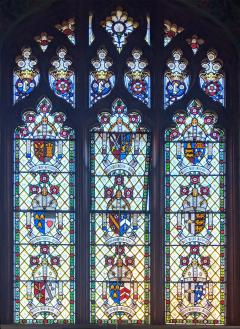

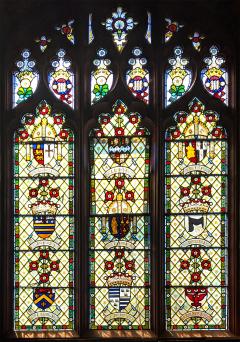

1858/9: The present stained glass (by Hardman of Birmingham) began to be installed. On the east side, the stained glass shows armorial bearings of Bishops who had been members of Queens’.

1858/9: The present stained glass (by Hardman of Birmingham) began to be installed. On the east side, the stained glass shows armorial bearings of Bishops who had been members of Queens’.

The stained glass for all four side windows was ordered at the same time in September 1858 [Hardman Tidy Order Book 1858–61, f. 282]. The order specified that the tracery was to be done first, that it may be built in with new stone work.

For a key to the arms, see Old Hall glass, and see below for a discussion of the emblems under crowns in the tracery.

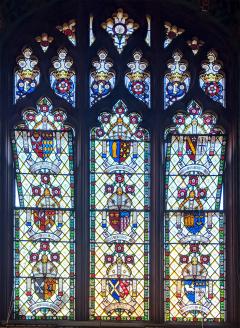

On the west side the stained glass shows armorial bearings of benefactors. The last window to be filled was the southern window on the west side (shown on the left), which includes the arms of the benefactor Robert Moon (bottom right) who paid for all this work. Photographs exist [such as this] of this window with stained glass already in the tracery, but plain glass filling the main lights.

On the west side the stained glass shows armorial bearings of benefactors. The last window to be filled was the southern window on the west side (shown on the left), which includes the arms of the benefactor Robert Moon (bottom right) who paid for all this work. Photographs exist [such as this] of this window with stained glass already in the tracery, but plain glass filling the main lights.

For a key to the arms, see Old Hall glass, and see below for a discussion of the emblems under crowns in the tracery.

1861–4: The former classical fireplace (as seen above in the prints of 1815 and 1842) was removed, revealing the relics of the original clunch arched medieval fireplace behind. A new fireplace was erected, designed by the architect G.F. Bodley, of alabaster and tiles. The remnants of the cut-away medieval clunch arch can still be seen if you look up inside the fireplace arch.

1861–4: The former classical fireplace (as seen above in the prints of 1815 and 1842) was removed, revealing the relics of the original clunch arched medieval fireplace behind. A new fireplace was erected, designed by the architect G.F. Bodley, of alabaster and tiles. The remnants of the cut-away medieval clunch arch can still be seen if you look up inside the fireplace arch.

The decoration of the fireplace includes a red rose (House of Lancaster: Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou), a white rose (House of York: Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville), and the college’s motto: Floreat Domus.

The grate was from Hart & Son.

Philip Webb designed eleven coats of arms, painted above the fireplace. A key to the arms is given in the table below.

| Sir John Wenlock | Marmaduke Lumley Bishop of Carlisle Bishop of Lincoln |

William Booth Bishop of Lichfield Archbishop of York |

Richard III | Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou |

Andrew Dokett | Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville |

Sir Thomas Smith | Anthony Sparrow President Bishop of Exeter Bishop of Norwich |

George Harry Grey 5th Earl of Stamford |

Robert Moon Fellow |

| Laid foundation stone | Benefactor | Benefactor | Benefactor | Foundress | Founding president | Foundress | Benefactor | Benefactor | Benefactor | Benefactor |

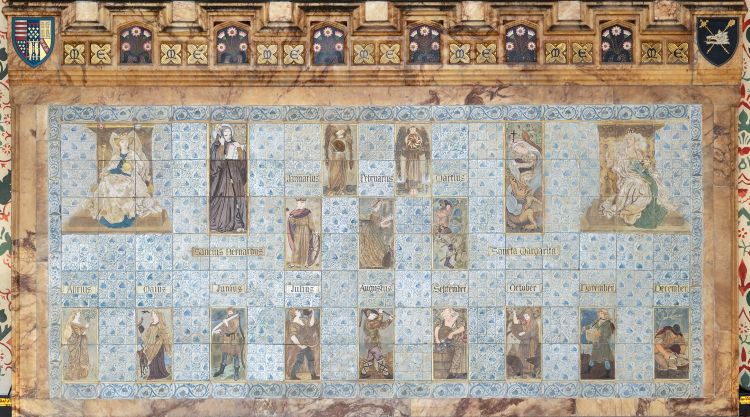

The tiles above the fireplace, depicting Labours of the Month, the two patron saints, and the angels of Night and of Day, were made by Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. in 1864 to the designs of Burne-Jones, Morris, Madox Brown, and Rossetti.

The tiles above the fireplace, depicting Labours of the Month, the two patron saints, and the angels of Night and of Day, were made by Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. in 1864 to the designs of Burne-Jones, Morris, Madox Brown, and Rossetti.

For more information on these tiles, see the page: Morris & Co Tiles.

| Margaret of Anjou | Angel of Night |

Angel of Day |

Elizabeth Woodville | |||||||||||||

| January | February | March | ||||||||||||||

| St Bernard | St Margaret | |||||||||||||||

| April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | ||||||||

1862–3: A tiled floor was laid, using stone and encaustic tiles by W. Godwin of Lugwardine. This floor was removed and replaced by a reproduction in 2003: only the oriel window floor and some specimen tiles survive from this period.

1863: The saying of Grace before and after dinner was revised or introduced.

All the work between 1846 and 1864 was paid for by Robert Moon, Fellow 1839–58, Barrister 1844, whose arms appear as one of the benefactors in the west windows, and above the fireplace. He was elected the first Honorary Fellow in 1868.

1865: 22 chairs for High Table bought from Howard & Sons.

1873: Ford Madox Brown drew designs for tiles of Margaret of Anjou and Elizabeth Woodville, to be added to the tiles already above the fireplace (see 1861–4). The tiles were made by Morris & Co. for £24 10s. [invoice]. The college still possesses the original drawings.

1875: The present decorative scheme for the walls and roof was designed by G.F. Bodley and executed by F.R. Leach, for £345 18s 2d, including the gilding of 885 lead castings of stars in the roof [invoice]. Each of the large stars weighs 14 ounces (0·4kg). A carved and moulded wood canopy to Bodley’s design was made by Cambridge firm Rattee & Kett and added above the Morris tiles of 1864 [invoice]. Hidden from view behind the wood canopy are the original wall decorations of 1875 by Leach, untouched by the later redecorations. The Latin Graces written around the walls are described here.

1875: The present decorative scheme for the walls and roof was designed by G.F. Bodley and executed by F.R. Leach, for £345 18s 2d, including the gilding of 885 lead castings of stars in the roof [invoice]. Each of the large stars weighs 14 ounces (0·4kg). A carved and moulded wood canopy to Bodley’s design was made by Cambridge firm Rattee & Kett and added above the Morris tiles of 1864 [invoice]. Hidden from view behind the wood canopy are the original wall decorations of 1875 by Leach, untouched by the later redecorations. The Latin Graces written around the walls are described here.

The work 1873–75 was paid for by Campion, Wright, and Pirie, Fellows.

[In this decorative scheme, prominent features are four angels at eaves level, projecting horizontally into the hall. The heads and wings are separate items, but the bodies appear to be carved out of the truncated remnants of tie-beams, still securely jointed into the original roof structure. This raises questions: why would tie-beams have been cut away? Surely not just for decorative effect? After all, the tie-beams serve an essential function in preventing the weight of the roof pushing the walls outwards. During the period when there were attic rooms above the hall, the attic floor level was below the level of the tie-beams. Here is my hypothesis, for which I have no evidence at all: some of the tie-beams were cut away to make way for attic floor-space, and ease circulation.]

[In this decorative scheme, prominent features are four angels at eaves level, projecting horizontally into the hall. The heads and wings are separate items, but the bodies appear to be carved out of the truncated remnants of tie-beams, still securely jointed into the original roof structure. This raises questions: why would tie-beams have been cut away? Surely not just for decorative effect? After all, the tie-beams serve an essential function in preventing the weight of the roof pushing the walls outwards. During the period when there were attic rooms above the hall, the attic floor level was below the level of the tie-beams. Here is my hypothesis, for which I have no evidence at all: some of the tie-beams were cut away to make way for attic floor-space, and ease circulation.]

1900: The first electric lighting installed.

1900: The first electric lighting installed.

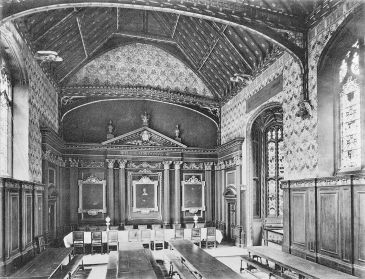

The photograph to the left, of unknown date, shows the Hall before the installation of electric lighting, with no apparent means of lighting apart from portable oil lamps.

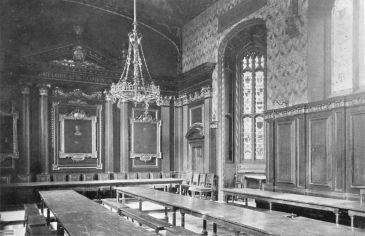

The photograph to the right shows an ornate electric chandelier, and side lights, apparently not yet completely installed. Published in 101 Views of Cambridge, by Rock & Co., undated, not later than 1905.

1909: Hall re-roofed with tiles instead of slate, parapets removed. Dated to 1909 by a fragment of newspaper found in 2005 behind a wallplate. [The Dial, No. 9, 1910 Michaelmas, pp. 32–4]

1909–10: Hall internally redecorated by Leach & Son [Conclusion Book 1909 June 19, 1910 April 30].

1948: It appears likely that the wall decorations were touched up for the celebrations of the quincentenary of the College.

ca. 1951: Louvre of 1846 removed from centre of the roof of the Hall. Its previous location is marked by the presence of cut rafters. [Queens’ College 1950–1951, p. 6]

1961: The wall and roof decorations were completely repainted, using stencils to reproduce the patterns (the original 1875 work had been painted free-hand). The colour of the panelling was changed from Bodley’s dark green to black with gold leaf relief on the advice of S.E. Dykes Bower.

1978: The Hall ceased being used on a daily basis, with the opening of the new dining hall and kitchens in Cripps Court. The fireplace was unblocked. From this time onwards the Old Hall (as it now became known) has been used for feasts, special functions, recitals, and receptions.

1979: Dimmable lighting system installed: survived until 2017. [Queens’ College Record 1980, p. 6]

1981: Internal remodelling of set I1 to create public access corridor to gallery of Old Hall. Gallery floor re-laid in three stepped tiers. [Queens’ College Record 1982, p. 5]

1983: Fireplace returned into use with a gas-fired log effect fire. [Queens’ College Record 1984, p. 7]

2001: Hall re-roofed with handmade tiles, thermal insulation inserted. Chimney stack over hall fireplace strengthened and repaired.

2003: The high-table wood dais and the tiled floor of 1862 were removed, to be replaced by a tile and stone floor in reproduction of the 1862 one, with newly made encaustic tiles from Craven Dunnill Jackfield. Where the previous dais had been, the new tile floor incorporated underfloor heating, enabling two visible radiators to be removed from the classical panelling.

2003: The high-table wood dais and the tiled floor of 1862 were removed, to be replaced by a tile and stone floor in reproduction of the 1862 one, with newly made encaustic tiles from Craven Dunnill Jackfield. Where the previous dais had been, the new tile floor incorporated underfloor heating, enabling two visible radiators to be removed from the classical panelling.

2003: After the old floor had been removed, the tops of the cellar vaults underneath were exposed. In this photograph, looking south, the far vault is one of the original cellars, probably originally connected to the river by a tunnel under Cloister Court. The nearer vault is a later addition: it has buttresses on both sides made of re-used stone and rubble to stabilise the arch.

2003: After the old floor had been removed, the tops of the cellar vaults underneath were exposed. In this photograph, looking south, the far vault is one of the original cellars, probably originally connected to the river by a tunnel under Cloister Court. The nearer vault is a later addition: it has buttresses on both sides made of re-used stone and rubble to stabilise the arch.

During these works, an old crooked doorway was uncovered at the north-east corner of the hall, connecting with the diagonal window bay of the Combination Room looking out onto Old Court. This doorway had been covered for many centuries by panelling on both sides, but the doorway itself had never been filled in: perhaps why there seems to be little acoustic isolation between the Hall and the Combination Room.

2005: Smoke detection, fire alarms, and emergency exit signs installed. Cleaning undertaken of: the wall and roof decorations, the fireplace and mantel (including the tiles by Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co), and the stained glass windows. The fireplace surround was restored, including the removal of some 1970s overpainting of the part immediately under the mantel shelf. The blue swan tiles of Morris & Co were lightly overpainted to restore the faded pattern. The photograph shows the before-and-after affect of the cleaning of the wall decoration: the dark uncleaned area was primarily contaminated by decades of nicotine, and the grime which adheres to the sticky nicotine surface. Apart from the oriel window, very little of the 1961 paintwork needed restoration: just chemical cleaning was all that was required. [Condition Assessment and Treatment Report for the Old Hall, by Hirst Conservation]

2005: Smoke detection, fire alarms, and emergency exit signs installed. Cleaning undertaken of: the wall and roof decorations, the fireplace and mantel (including the tiles by Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co), and the stained glass windows. The fireplace surround was restored, including the removal of some 1970s overpainting of the part immediately under the mantel shelf. The blue swan tiles of Morris & Co were lightly overpainted to restore the faded pattern. The photograph shows the before-and-after affect of the cleaning of the wall decoration: the dark uncleaned area was primarily contaminated by decades of nicotine, and the grime which adheres to the sticky nicotine surface. Apart from the oriel window, very little of the 1961 paintwork needed restoration: just chemical cleaning was all that was required. [Condition Assessment and Treatment Report for the Old Hall, by Hirst Conservation]

2017: New LED-based lighting system, new P.A. and hearing aid induction loop.

Iconography

The decoration of the Old Hall includes elements that have meanings relevant to the history of the college.

The Daisy was the badge of Margaret of Anjou, the first foundress queen, as its alternative name, marguerite, is her name in French. Daisies can be seen in the stained glass of the side windows, and along the top of the over-mantel.

The Daisy was the badge of Margaret of Anjou, the first foundress queen, as its alternative name, marguerite, is her name in French. Daisies can be seen in the stained glass of the side windows, and along the top of the over-mantel.

The Red Rose was the symbol of the House of Lancaster, to which belonged King Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou, first foundress queen. The White Rose was the symbol of the House of York, to which belonged King Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, second foundress queen. The civil war between these two parties for the crown of England is retrospectively known as the War of the Roses. Red and white roses can be seen on the fireplace, and in the stained glass in the tracery of the side windows.

The Red Rose was the symbol of the House of Lancaster, to which belonged King Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou, first foundress queen. The White Rose was the symbol of the House of York, to which belonged King Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, second foundress queen. The civil war between these two parties for the crown of England is retrospectively known as the War of the Roses. Red and white roses can be seen on the fireplace, and in the stained glass in the tracery of the side windows.

The angels (a) at eaves level, and (b) supporting the brackets for the tie-beams, all bear shields carrying a letter written in gothic (black-letter) script. The two eaves-level angels on the east side carry the letters ‘M’ and ‘E’, for the two foundress queens: their counterparts on the west side carry the letters ‘M’ and ‘B’ for the two patron saints. The lower angels (illustrated here) carry ‘M’ and ‘E’ on both sides. The letters ‘M’ and ‘E’ also occur along the top of the over-mantel, alternating with daisies.

The angels (a) at eaves level, and (b) supporting the brackets for the tie-beams, all bear shields carrying a letter written in gothic (black-letter) script. The two eaves-level angels on the east side carry the letters ‘M’ and ‘E’, for the two foundress queens: their counterparts on the west side carry the letters ‘M’ and ‘B’ for the two patron saints. The lower angels (illustrated here) carry ‘M’ and ‘E’ on both sides. The letters ‘M’ and ‘E’ also occur along the top of the over-mantel, alternating with daisies.

In the stained glass of the tracery of the side windows appears an alternating sequence of emblems under crowns. These appear to represent monarchs, and/or their queens, with which the early college was associated. On the west side (shown to the left), the second emblem shows a gothic letter ‘m’, superimposed on a red rose, and supported on either side by ostrich feathers, a symbol associated with King Henry VI: this emblem clearly represents Queen Margaret (of Anjou), the first foundress queen. On the east side (shown to the right), the first emblem shows a gothic letter ‘e’, supported on either side by white roses, a symbol associated with King Edward IV: this emblem clearly represents Queen Elizabeth (Woodville), the second foundress queen. The other emblem on the west side shows an uprooted white rose, which might be a reference to King Richard III, killed in battle, who was a great benefactor, as was his queen Anne Neville. The second emblem on the east side shows a Tudor rose, the emblem of King Henry VII, whose queen was Elizabeth of York, the daughter of the second foundress Queen Elizabeth.

In the stained glass of the tracery of the side windows appears an alternating sequence of emblems under crowns. These appear to represent monarchs, and/or their queens, with which the early college was associated. On the west side (shown to the left), the second emblem shows a gothic letter ‘m’, superimposed on a red rose, and supported on either side by ostrich feathers, a symbol associated with King Henry VI: this emblem clearly represents Queen Margaret (of Anjou), the first foundress queen. On the east side (shown to the right), the first emblem shows a gothic letter ‘e’, supported on either side by white roses, a symbol associated with King Edward IV: this emblem clearly represents Queen Elizabeth (Woodville), the second foundress queen. The other emblem on the west side shows an uprooted white rose, which might be a reference to King Richard III, killed in battle, who was a great benefactor, as was his queen Anne Neville. The second emblem on the east side shows a Tudor rose, the emblem of King Henry VII, whose queen was Elizabeth of York, the daughter of the second foundress Queen Elizabeth.

The phrase Floreat Domus is the motto of the college, meaning: May this house flourish.

The phrase Floreat Domus is the motto of the college, meaning: May this house flourish.

The armorial bearings of the college (derived from those of Margaret of Anjou) can be seen at the top of the panelling at the centre of the north end (behind High Table); the boar’s head badge can be seen at the centre of the south end, between the two entry doors from the screens passage. These two devices can be seen again at each end of the over-mantel, at the top.

The armorial bearings of the college (derived from those of Margaret of Anjou) can be seen at the top of the panelling at the centre of the north end (behind High Table); the boar’s head badge can be seen at the centre of the south end, between the two entry doors from the screens passage. These two devices can be seen again at each end of the over-mantel, at the top.

The painted tiles of the over-mantel, displaying the Angel of Night, the Angel of Day, and the Labours of the Months, could be read as having a theme of the passing of time.

Links

Drama and theatre at Queens’.

Old Hall stained glass inscriptions 1854–8.

The Graces of Queens’ College, with translations into English.

Morris & Co. tiles 1861–4.

Further reading

1837–42: Le Keux’s Memorials of Cambridge, by Thomas Wright and Harry Longueville Jones, Vol. 1, pp. 264–6.

1860: Memorials of Cambridge, by Charles Henry Cooper, illustrated by John Le Keux and Storer & Storer, Vol. 1, pp. 322–3;

1886: The Architectural History of the University of Cambridge, by Robert Willis and John Willis Clark, Volume 2, pp. 44–48. (OCLC 6104300)

1904: English and Scottish wrought ironwork, by Bailey Scott Murphy, p. 4 and Plate 41. (OCLC 56705227) [Old Hall gates]

1923: College Plays performed in the University of Cambridge, by George Charles Moore Smith.

1923: The Academic Drama at Cambridge: Extracts from college records, by George Charles Moore Smith, in the Malone Society Collections, Vol. 2, Pt. 2, pp. 150–231, Queens’ at pp. 182–204. (OCLC 1909297)

1952: The Fabric, in Queens’ College 1950–1951, p. 6.

1959: Shakespeare’s Wooden O, by J. Leslie Hotson, Queens’ at pp. 169–72, 218–9. (OCLC 359088) [Over-optimistic reconstruction of demountable theatre in Old Hall]

1959: An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the City of Cambridge, by the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (England), Part II, pp. 172–3. (online version)

1961: The Fabric, in Queens’ College 1959–1960, p. 6.

1962: The Fabric, in Queens’ College 1960–1961, p. 9.

1980: Morris & Company in Cambridge : catalogue, by Duncan Robinson and Stephen Wildman[Fellow], pp. 26–9. (ISBN 978-0-521-23310-1, 978-0-521-29903-9)

1981: The Old Hall, by Stephen Wildman[Fellow], in Queens’ College Record 1981, p. 8. [decorative scheme]

1986: An early stage at Queens’, by Iain Richard Wright [Fellow], in Cambridge: Magazine of the Cambridge Society, vol. 18, pp. 74–83; (ISSN 0140-8348)

1996: another edition, in Studies in Theatre Production, vol. 13, issue 1. (ISSN 1357-5341)

1989: Records of Early English Drama: Cambridge, Volume 1: The Records, by Alan H. Nelson; (ISBN 978-0-8020-5751-8)

1989: Volume 2: Editorial apparatus.

1992: Hall Screens and Elizabethan Playhouses: Counter-Evidence from Cambridge, by Alan H. Nelson, in The Development of Shakespeare’s Theater, ed. John Astington, pp. 57–76. (ISBN 978-0-404-62293-0)

1994: Early Cambridge theatres: college, university, and town stages, 1464-1720, by Alan H. Nelson. (ISBN 978-0-521-43177-4)

1996: William Morris Tiles : The Tile Designs of Morris and his Fellow-Workers, by Richard and Hilary Myers, pp. 62–67 and plates 25–29. (ISBN 978-0-903685-43-6) [Old Hall fireplace overmantel]

1999: The Tile Decoration by Morris & Co. for Queens’ College, Cambridge: The Inspiration of Illuminated Manuscripts, by Michaela Braesel, in Apollo 149, no. 443 (January 1999), pp. 25–33. (ISSN 0003-6536) [reproduced by kind permission of Apollo Magazine and of the author]

2002: The Fabric, by Robin Walker, in Queens’ College Record 2002, p. 7. [roof replacement]

2004: Queens’ College, Cambridge : archaeological monitoring of floor replacement, by Jess Tipper, Cambridge Archaeological Unit.

2004: The Fabric, by Robin Walker, in Queens’ College Record 2004, p. 8. [floor replacement]

2005: Condition Assessment and Treatment Report for the Old Hall, Queens’ College, by Hirst Conservation. [by permission]

2005: Biographical Dictionary of English Wrought Iron-Smiths of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, by Edward Saunders, in The Volume of the Walpole Society, Vol. 67, pp. 237–384 at p. 303. (ISSN 0141-0016) [Old Hall gates by Jonas Jackson]

2006: The Old Hall Restoration, by Robin Walker, in Queens’ College Record 2006, pp. 18–20. [cleaning and restoration]

2014: SET free: breaking the rules in a processual, user-generated, digital performance edition of Richard the Third, by Jennifer Roberts-Smith et al., in The Shakespearean International Yearbook, 14: Special Section, Digital Shakespeares, ed. Brett D. Hirsch; D. Hugh Craig, pp. 69–100. (ISBN 978-1-4724-3964-2) [simulation of hypothetical 1588 performance on demountable stage in Old Hall]

2016: The Heraldry of Queens’ College, Cambridge, by David Broomfield.