A possible reason might be that much of the work was financed by the President of the time, out of his private means, and so never featured in the college Bursar’s records.

The internal panelling, at least, can be confidently ascribed to the period of Humphrey Tindall, President 1579–1614: he left it to the college in his will.

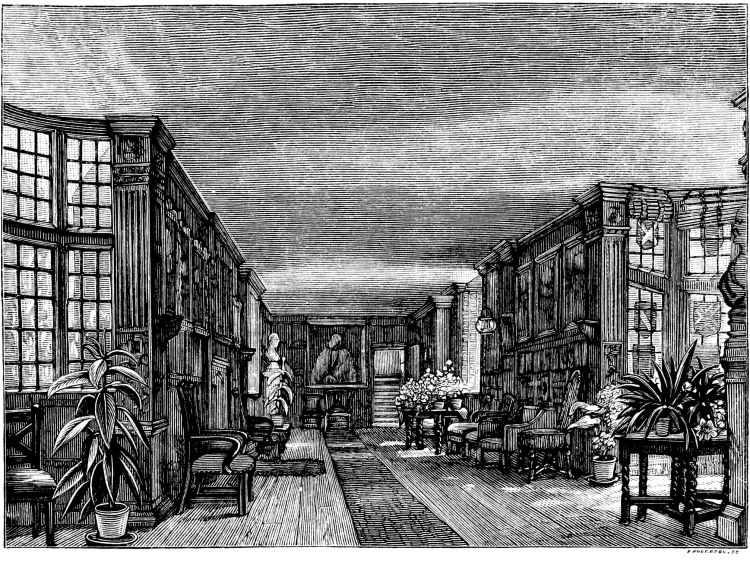

This view looks eastwards from the normal entry point for visitors to the Long Gallery from the main Lodge staircase.

This view is in the reverse direction, looking west from a location close to the Essex Room.

This view is in the reverse direction, looking west from a location close to the Essex Room.

On the left is a small collection of paintings from the Parliamentary period, including Cromwell and his associates. By contrast, portraits of the royal family are on the opposite wall, gathered around the fireplace.

On the right, the doors to the staircase down to the garden are shown open. The carved semi-circular frame to that opening appears to pre-date the panelling.

On the back of a panelled door at the east end of the gallery can be found the date 1604 scratched in the wood, suggesting that the panelling was in place by that date.

On the back of a panelled door at the east end of the gallery can be found the date 1604 scratched in the wood, suggesting that the panelling was in place by that date.

The panelling is at its most decorative above the fireplace. The fireplace itself was blocked by a stove heater until 1897, when central heating was installed, and the fireplace unblocked to reveal the present arrangement.

The panelling is at its most decorative above the fireplace. The fireplace itself was blocked by a stove heater until 1897, when central heating was installed, and the fireplace unblocked to reveal the present arrangement.

On each side of the fireplace can be seen examples of the fluted columns that break up the gallery panelling into bays. Each column has a lion’s head carving at the top. Just under the lion’s head is carved decoration which uses an incised letter ‘N’ as a repeated motif. It is not known whether this is intended to mean anything, nor, if so, what.

There appear to be two different designs of lion’s head around the Long Gallery. It is possible that they might represent two different periods of work, or repairs.

The large side-windows and oriel windows are, I assert, not original, but the panelling is designed around their presence, so the panelling must have been put up after those large windows had been inserted in an older structure.

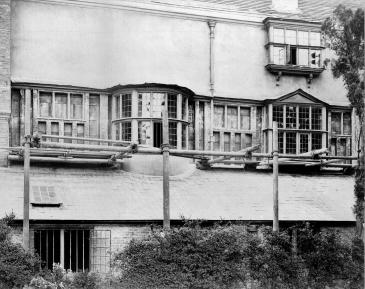

There were originally, in addition, smaller windows, intermediate to the surviving larger ones, still present when the panelling was erected. At some date after the panelling was put up, the smaller windows were stopped up, and the panelling patched to cover where the windows had been. The original panelling had been hardwood, but the patches over the stopped-up windows were made of softwood. In the days when the panelling was painted, the type of wood would not have mattered much, but now that the panelling is unpainted, the softwood has been stained and grained to match the surrounding hardwood originals. An observant viewer can still see where the blocked windows were in the panelling. The frames of the stopped-up windows were discovered during maintenance work in 1898: they survived under the panelling until 1912, when the outside of the building was re-plastered in half-timbered form. [The Queen’s College of S. Margaret and S. Bernard (1448–1898), by John Willis Clark, 1898, p. 3]

There were originally, in addition, smaller windows, intermediate to the surviving larger ones, still present when the panelling was erected. At some date after the panelling was put up, the smaller windows were stopped up, and the panelling patched to cover where the windows had been. The original panelling had been hardwood, but the patches over the stopped-up windows were made of softwood. In the days when the panelling was painted, the type of wood would not have mattered much, but now that the panelling is unpainted, the softwood has been stained and grained to match the surrounding hardwood originals. An observant viewer can still see where the blocked windows were in the panelling. The frames of the stopped-up windows were discovered during maintenance work in 1898: they survived under the panelling until 1912, when the outside of the building was re-plastered in half-timbered form. [The Queen’s College of S. Margaret and S. Bernard (1448–1898), by John Willis Clark, 1898, p. 3]

At intervals, the panelling has columns projecting slightly into the room, with a lion’s-head mask at the top of each column. These columns are (mostly) the locations of the primary load-bearing vertical posts of the building, which are of a larger section than the intermediate studs, and are supported by the outer ends of massive horizontal beams spanning the cloister below. It is to be noted that the westernmost window on the northern side severed one of those primary load-bearing posts (which supports the notion that the large windows were a later addition to the building). While the building around the window slumped downwards for lack of support, the stump of the severed primary post pushed upwards in the middle of the window sill, which is now visibly distorted.

At intervals, the panelling has columns projecting slightly into the room, with a lion’s-head mask at the top of each column. These columns are (mostly) the locations of the primary load-bearing vertical posts of the building, which are of a larger section than the intermediate studs, and are supported by the outer ends of massive horizontal beams spanning the cloister below. It is to be noted that the westernmost window on the northern side severed one of those primary load-bearing posts (which supports the notion that the large windows were a later addition to the building). While the building around the window slumped downwards for lack of support, the stump of the severed primary post pushed upwards in the middle of the window sill, which is now visibly distorted.

The two decorated columns on each side of this window are examples of columns which are not the site of primary load-bearing vertical posts.

The Long Gallery was shortened slightly by the building of the 1791 main staircase, which intruded into the north-west corner of the timber structure. The gallery was re-balanced by shortening it an equal amount on the south side by erection of an internal partition. In the resulting cupboard can be seen a length of lost side panelling painted an arsenic green. The paint was removed from the panelling in the Long Gallery in 1857. [AHUC, Vol. 2, p. 28n]

Views of the Long Gallery interior

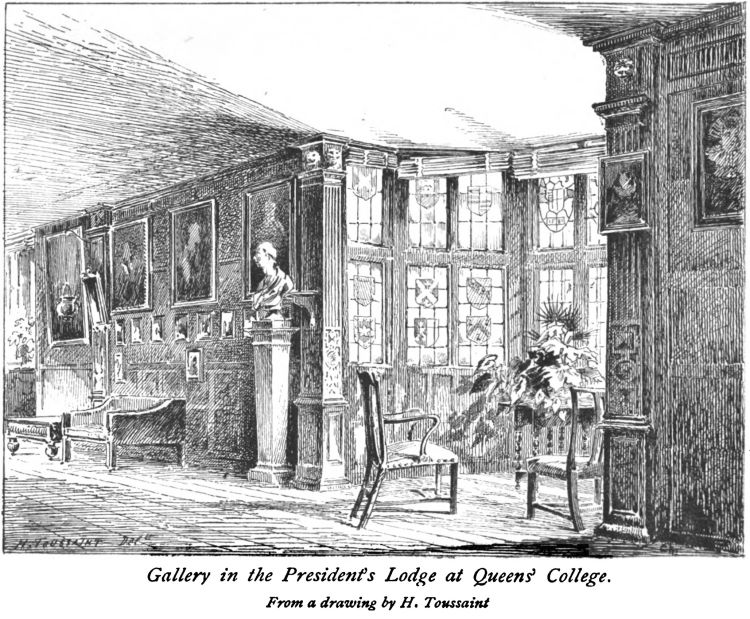

A drawing of the Long Gallery oriel window by Henri Toussaint in 1880. First published in Cambridge: Brief Historical and Descriptive Notes, by John Willis Clark, 1881.

A drawing of the Long Gallery oriel window by Henri Toussaint in 1880. First published in Cambridge: Brief Historical and Descriptive Notes, by John Willis Clark, 1881.

A woodcut print of the Long Gallery interior, looking east.

A woodcut print of the Long Gallery interior, looking east.

It was first published in the Architectural History of the University of Cambridge, by Willis & Clarke, 1886, Vol. 2, p. 33, but possibly drawn earlier.

It was probably drawn by John O’Connor, and engraved on wood by F. Anderson. [AHUC, Vol. 1, Preface, p. xxviii]

The prominent cast-iron radiators and shelves visible in this photograph (ca 1948–50) were installed in 1897–8 when a boilerhouse and central heating were installed in the Lodge: the radiators were removed in 1983–4 in favour of skirting heaters running at lower temperatures.

The prominent cast-iron radiators and shelves visible in this photograph (ca 1948–50) were installed in 1897–8 when a boilerhouse and central heating were installed in the Lodge: the radiators were removed in 1983–4 in favour of skirting heaters running at lower temperatures.

The oriel window stained glass

Although there are two older pieces of glass in the centre of the oriel window, most of the stained glass coats of arms in the windows were moved here around 1846–54, having previously been erected in the Hall 1819–22. The moved glass was by Charles Muss, the majority being the arms of former presidents. At first, this moved glass was hung from wires inside the windows. Photographic evidence suggests that at some point between 1952 and 1959, the leaded lights were re-made with the stained glass integrated.

Although there are two older pieces of glass in the centre of the oriel window, most of the stained glass coats of arms in the windows were moved here around 1846–54, having previously been erected in the Hall 1819–22. The moved glass was by Charles Muss, the majority being the arms of former presidents. At first, this moved glass was hung from wires inside the windows. Photographic evidence suggests that at some point between 1952 and 1959, the leaded lights were re-made with the stained glass integrated.

The arms of the Presidents missing from this sequence, being those who served also as Bishops, are displayed in the bay window of the Audit Dining Room. Also missing are the two Presidents of the commonwealth period, between the two presidencies of Edward Martin.

| Andrew Dokett President 1 1448–84 |

Thomas Wilkinson President 2 1484–1505 |

Grey/Booth in error |

Queens’ College 1589 |

Humphrey Tindall 1597 |

John Mansell President 17 1622–31 |

Edward Martin President 18 & 21 1631–44 1660–62 |

William Wells President 23 1667–75 |

| John Jenyn President 5 1519–25 |

Robert Bekensaw President 4 1508–19 |

William Franklyn President 7 1527–9 |

Humphrey Tindall President 15 1579–1614 |

John Stokes President 13 1560–8 |

Robert Plumptre President 27 1760–88 |

John Davies President 25 1717–32 |

William Sedgwick President 26 1732–60 |

| Simon Heynes President 8 1529–37 |

William Mey President 9 & 12 1537–53 1559–60 |

Thomas Peacock President 11 1557–59 |

Henry James President 24 1675–1717 |

Isaac Milner President 28 1788–1820 |

Thomas Farman President 6 1525–7 |

A number of errors in this heraldry require discussion, not least because those errors have propagated from here to other locations:

- the light third from left in the top row displays the arms of Grey/Booth, the arms of the three brothers Grey (mother Booth) who donated in 1766 the pictures over High Table in the Old Hall. These arms do not belong in a sequence of arms of past Presidents. They appear in the chronological sequence where one would expect to see the arms of Robert Bekensaw, President 4. The error of taking this design to be the arms of Bekensaw is repeated in (a) the1854 glass of the oriel window of Old Hall; and (b) the 1923 ceiling of the Long Gallery (see below).

- the light second from left in the middle row, where one would expect to see the arms of Thomas Farman, President 6, display in fact the arms of Robert Bekensaw, as attested (approximately) in Cooper [Athenae Cantabrigiensis, 1858, Vol. 1, p. 33] and in Searle [History of QCC, 1867, Vol. 1, p. 159]. The error of taking this design to be the arms of Thomas Farman is repeated in the oriel window of Old Hall.

- the light far right in the bottom row appears to be the arms of Thomas Farman, President 6, as attested in Cooper (erroneously per bend) [Athenae Cantabrigiensis, 1858, Vol. 1, p. 37], in RCHM [Cambridge, 1959, Part 2, p. 175], and recognisable as a variant of arms for a Forman family [Burke’s General Armory, 1884, p. 367], but shown incorrectly in this window as paly wavy instead of barry wavy.

The oval arms of the college dated 1589 are similar in design concept to the oval arms of Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, on display in the Essex Chamber, so they might originally have been a pair. These oval arms of the college were found smashed the morning after a student demonstration in Cloister Court held at 2 a.m. on 1969 November 30, protesting about guest regulations [CM 266; GB Minute VI of 1969 December 5; Cambridge Evening News No. 24944, 1969 Dec 1, p. 12]. No evidence was found that the demonstration had been responsible for the damage. According to oral tradition, the damage was caused by a snowball. After repair of the pieces that could be salvaged, the stained glass now hangs in its own frame, behind plain glass in the external window.

The oval arms of Humphrey Tindall have been damaged and repaired in plain glass, so that the last digit of the date can no longer be seen. In 1931, the date was recorded as 1597 [Country Life, Vol. LXIX, No. 1781, 1931 March 7, p. 295].

The ceiling

The ceiling was originally plain flat plaster on rushes. In 1923, the current ceiling of decorated plaster was put up to the design of Cecil Greenwood Hare, architect. The design was inspired by that of the ceiling of the Long Gallery at Haddon Hall, Derbyshire. In the 19th century, Professor Robert Willis had pointed out that the ground-plan of Queens’ College was similar to that of a secular manor house (rather than, say, a monastery), and, in particular, to that of Haddon Hall. The new ceiling of 1923 artificially reinforced that resemblance. The architect wrote:

The new plaster ceiling is designed to harmonise with the old world atmosphere of its surroundings. Although not a slavish copy, it is founded on similar lines to the fine ceiling in the long gallery at Haddon Hall, Derbyshire. The ceiling is divided by moulded single ribs into large quatre-foil panels having modelled terminal sprays. In the centre of the panels are enriched bosses, or pendants, and Coats of Arms are arranged in the panels at intervals.

There were Coats of Arms embedded in the ceiling:

These, eight in number, arranged in four pairs, are:

(1) Those of the two Foundresses.

(2) That of Andrew Dokett, the first President (1448), and that of Robert Bekenshaw (1508), President when a gallery was built. [The arms shown for Bekenshaw are erroneously those of Grey/Booth: an error that seems to have been inherited from stained glass in the Long Gallery and in the Old Hall]

(3) Those of Simon Heynes (1528), and William Mey (1537), Presidents when the Gallery was built. [These mistakenly rely on the dating of Willis & Clark, which is no longer supportable]

(4) That of Humphrey Tyndall (1579), the President who put the panelling in the Gallery, and that of the present President to give the date of the new ceiling (1923).

[The New Ceiling in the Gallery of the Lodge, by T.C. Fitzpatrick, in The Dial, No. 48, Easter Term 1924, p. 19]

Notable furniture

Erasmus’s Chair.

Milner’s Chair.

Vigani’s Cabinet and collection of Materia Medica 1703–4.

Edward East clock 1664.

Links

Long Gallery building history and illustrations.

The Essex Chamber (a side room off the Long Gallery).

The Essex Wing, containing the Essex Chamber and the Kidman Staircase.

Further reading

1886: The Architectural History of the University of Cambridge, by Robert Willis and John Willis Clark, Volume 2, pp. 27–36. (OCLC 6104300)

1898: The Queen’s College of S. Margaret and S. Bernard (1448–1898), by John Willis Clark (OCLC 55865473) [for 450th anniversary]

1924: The New Ceiling in the Gallery of the Lodge, by Thomas Cecil Fitzpatrick, in The Dial, No. 48, Easter Term 1924, p. 19.

1949: The President’s Lodge, Queens’ College Cambridge, in The Antique Collector, Vol. 20, No. 3 (May–June 1949), pp. 69–76. (ISSN 0003-5858)

1959: An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the City of Cambridge, by the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (England), Part II, pp. 175–6. (online version)

2016: The Heraldry of Queens’ College, Cambridge, by David Broomfield.