Pump Court is an irregular area to the south of Cloister Court.

Pump Court is an irregular area to the south of Cloister Court.

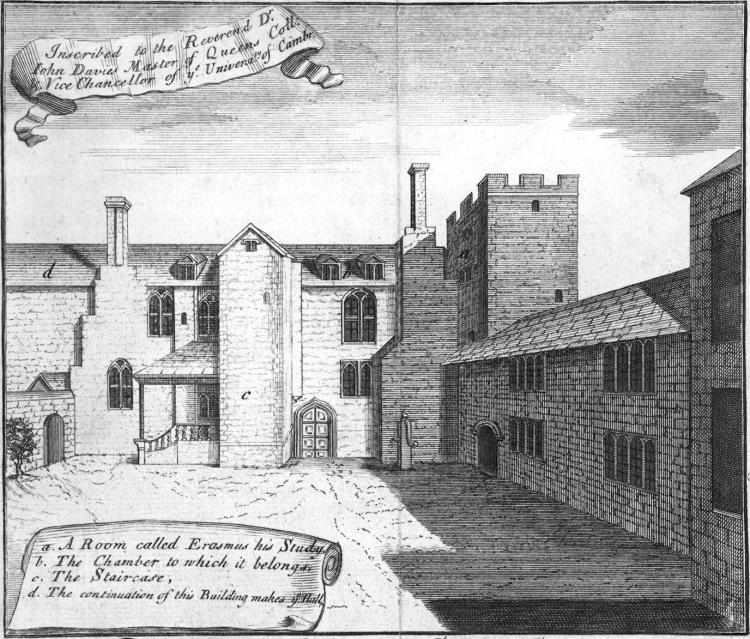

This view of Pump Court is taken from The Life of Erasmus, by Samuel Knight, 1726. It is the earliest known view (apart from bird’s-eye views) of any part of the college.

The eastern side of Pump Court consists of those parts of the original buildings of Old Court, 1449, which formed the kitchens and the rooms above, seen here in the centre. The northern side consists of the back wall of the southern cloisters of Cloister Court, built in the 1490s, seen here at the extreme left. The southern side, originally reaching to Small Bridges Street, had a building erected later, partly shown on the right of this view. The western side originally reached to the river. In the centre can be seen a large doorway to the kitchens, the inside arch of which can still be seen exposed at low level in the Old Kitchens today. The staircase (now known as staircase ‘I’) is shown in its original form, before it was extended to the south (thus presumably obliterating the doorway). The pump after which the court is named can be seen, and the south-west turret of Old Court, at the top of which Erasmus’s study was said to have been.

The view illustrates the oral tradition relating the location at which Erasmus of Rotterdam is said to have had a study in Queens’, 1511–14, when he was Lady Margaret Professor of Divinity in the university. Erasmus was neither a student nor a Fellow of Queens’, and therefore he probably cannot be formally counted as a member of Queens’. There is no mention of Erasmus in the archives of Queens’ College, so the college has no contemporary record of his visit. The period 1511–14 lies within the presidency of Robert Bekenshaw, and not John Fisher, as often assumed. Although Samuel Knight, and those who copied him, claimed Erasmus to have been invited to Cambridge by Fisher, and accommodated by him, no contemporary authority for those assertions was given then, and none has since been discovered. [Earlier, Erasmus had visited Cambridge briefly in 1506, and it is possible that Fisher might have been involved then, but again there is a lack of contemporary evidence for that]. Knight notes that there is a conflict between his claim that Fisher accommodated Erasmus, and the traditions circulating in college. [The Life of Erasmus, by Samuel Knight, p. 124 n.]

Yet the tradition persists. The first time it appeared in print was a century after Erasmus’s visit, when Thomas Fuller, who had been an undergraduate at Queens’ from 1622, wrote:

Queens Colledge accounteth it no small credit thereunto, that Erasmus (who no doubt might have pickt and chose what House he pleased) preferred this for the place of his study, for some years in Cambridge. Either invited thither with the fame of the learning and love of his friend Bishop Fisher then Master thereof, or allured with the situation of this Colledge so neer the River (as Roterdam his native place to the Sea) with pleasant walks thereabouts.

[History of the University of Cambridge, by Thomas Fuller, 1655, Sect. V, ¶39, p. 82]

About this time ERASMUS came first to Cambridge (coming and going for seven years together) having his abode in Queens Colledge, where a Study on the top of the South-west Tower in the old Court stil retaineth his name. Here his labour in mounting so many stairs (done perchance on purpose to exercise his body, and prevent corpulency) was recompensed with a pleasant prospect round about him.

[Ibid., Sect. V, ¶48, p. 87]

In the entry for Erasmus in Brief Lives, John Aubrey quotes a communication dated 1680 June 15 from Andrew Paschall, who had been an undergraduate at Queens’ from 1647 and a Fellow 1653–63:

The staires which rise up to his studie at Queens Colledge in Cambridge doe bring first into two of the fairest chambers in the ancient building; in one of them,[now known as I1] which lookes into the hall and chiefe court, the Vice-President kept in my time; in that adjoyning,[I2] it was my fortune to be, when fellow. The chambers over [I3,4] are good lodgeing roomes; and to one of them is a square turret adjoyning, in the upper part of which is that study of Erasmus; and over it leades. To that belongs the best prospect about the colledge, viz. upon the river, into the corne-fields, and countrey adjoyning, etc.; so that it might very well consist with the civility of the House to that great man (who was no fellow, and I think stayed not long there) to let him have that study. His keeping roome might be either the Vice-President’s, or, to be neer to him, the next; the room for his servitor that above, over it, and through it he might goe to that studie, which for the height, and neatnesse, and prospect, might easily take his phancy.

[Brief Lives, by John Aubrey, 1669–96, edited by Andrew Clark, 1898, pp. 247–8.]

Paschall’s account is consistent with the description in the view above, and they are probably both descended from the same oral tradition. The only certain thing in Paschall’s account is where that study

was believed to have been: the rest is written in a speculative way and he does not seem to be certain where Erasmus actually lodged. Although the caption to the view correctly identified the chamber in the attics to which the study belonged, that should not be taken to indicate that Erasmus lodged in that attic chamber, as Paschall explains. The interior of I staircase was extensively reorganised around 1911/12, and room partitions might have been moved, but the strange little square room at the top of the turret at the south-west corner of Old Court still exists, although one has to climb a ladder to reach it.

Pump Court

The layout of Pump Court in the 1680s may be ascertained from the bird’s-eye view and plan, both by Loggan. Several contiguous buildings are visible, of varying heights and styles. Willis & Clark, in their text [AHUC, Vol. 2, p. 18], identify only one date, 1564, when a building might have been erected in Pump Court, but their ground plan [AHUC, Vol. 4, Plan 15] shows 1534 for the range along Small Bridges Street. Loggan’s plan shows the Pump Court buildings to be connected to the riverside range, but the earlier 1592 bird’s-eye view by Hamond does not. So, I am inclined to think it is more probable that the pre-1680 buildings in Pump Court were a gradual accretion of various dates and styles, rather than all being attributable to 1564.

Pump Court was to change in 1756–60 when all the existing buildings (plus about 25 feet of the 1460s riverside building) were demolished, and the building now known as Essex Building was erected, forming an L-shape around the entire southern and western sides of Pump Court. The eponymous pump, shown in the view above, would have been built over at this time.

Around 1911/12, there were substantial internal alterations to the kitchens and the rooms above on I staircase: indeed, in the attics, very little fabric remains of any earlier date. On the first floor, the chambers that Paschall had inhabited (now known as I2, immediately above the kitchens) were gutted, given a concrete floor, its ceiling strengthened with steel joists, and reconstructed as a single open room. It was known initially as the Bernard Room. In 1926 it was made into the first Junior Common Room for students, and its name was changed to the Erasmus Room at about the same period. The student common-room provision was transferred to the former Fitzpatrick Hall around 1936. In 1964, the Erasmus Room became an overflow dining-room, served by a dumb-waiter from the kitchens below. For a period in the 1970s, the Erasmus Room served as the College Bar, until the new college bar opened in Cripps Court in 1975, after which the Erasmus Room was restored as a general meeting room.

In 1931, a single-storey extension to the kitchen sculleries was erected in front of the south wing of Essex Building, thus reducing the size of the courtyard. In 1990, during the refit of the Old Kitchens, the courtyard paving and cobbles were renewed.

In 2017, the courtyard paving was re-graded to bring it up to the level of the internal ground floor of Essex Building, to improve accessibility.

Further reading on Pump Court

1886: The Architectural History of the University of Cambridge, by Robert Willis and John Willis Clark, Vol. 2; pp. 15–18. (OCLC 6104300)

1916: The Pump, or Erasmus, Court before 1756, by Robert Hatch Kennett, in The Dial, No. 25 Lent 1916, pp. 12–19.

Further reading on Erasmus at Queens’

1726: The Life of Erasmus, by Samuel Knight. (OCLC 79519761)

1867: The History of the Queens’ College of St Margaret and St Bernard in the University of Cambridge, by William George Searle, Vol. 1, 1446–1560, Cambridge Antiquarian Society Octavo Publications No IX, pp. 134–7, 152–6. (OCLC 3279381)

1923: Erasmus Roteradamus, by Charles Sydney Deakin (1897–1970), in The Dial, No. 44, 1923 Lent, pp. 9–13.

1963: Erasmus and Cambridge : the Cambridge letters of Desiderius Erasmus, by Douglas Ferguson Scott Thomson & Harry Culverwell Porter (OCLC 25443686)

1970: reprint (ISBN 978-0-8020-5125-7)

1987: A History of Queens’ College, Cambridge, 1448–1986, by John Twigg, pp. 19–24. (ISBN 978-0-85115-488-6)