What we now call Cloister Court comprises buildings of many periods, including the earliest extensions of the original college (now Old Court).

The oldest building in Cloister Court, on the east side, is the west range of Old Court, comprising (from left to right) the SCR, the projecting staircase to the President’s Study, the Hall, Kitchens, staircase I, and Erasmus’s Tower, all built around 1449 (the SCR and President’s Study maybe slightly later).

The oldest building in Cloister Court, on the east side, is the west range of Old Court, comprising (from left to right) the SCR, the projecting staircase to the President’s Study, the Hall, Kitchens, staircase I, and Erasmus’s Tower, all built around 1449 (the SCR and President’s Study maybe slightly later).

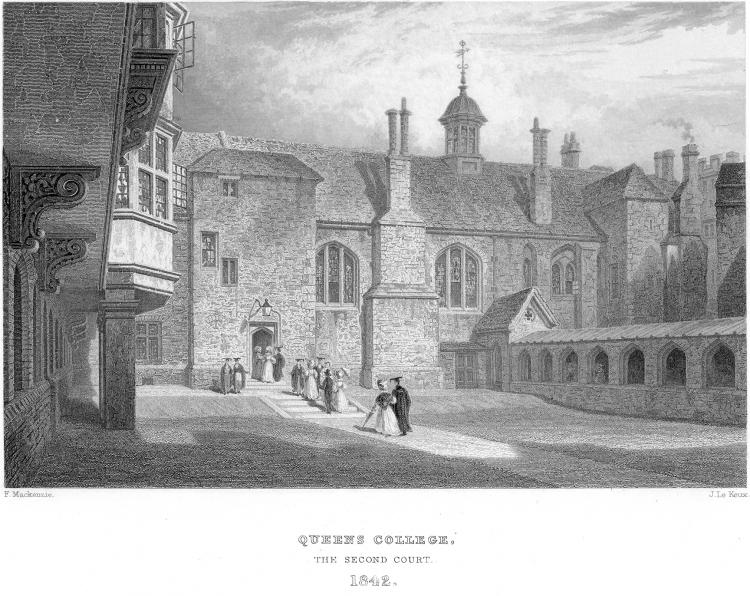

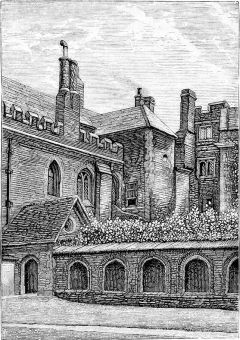

This view was drawn by F. Mackenzie, engraved by John Le Keux and first published in Le Keux’s Memorials of Cambridge, by Thomas Wright and Harry Longueville Jones, illustrated by John Le Keux, published part-form in 1837–42.

This view shows the state of the Hall before the changes of 1846 by Dawkes. The Hall windows have plain mullions, with no tracery and very little stained glass. There is no louvre on the roof (an inappropriate 1846 insertion by Dawkes), and the cupola for the dinner bell is seen in its pre-Dawkes design. Internally, the Hall has a flat ceiling, with attic rooms above, having dormer windows looking into Old Court: an unanswered question is by what means those rooms were accessed.

Some windows on the first floor of staircase I are strangely truncated in height, as if there is a lowered ceiling, or a mezzanine floor level, inside. They did not look like this in the 1726 view of Pump Court.

The ornamental brick chimneys on the stacks above the Hall and the Kitchens bear the date 1836.

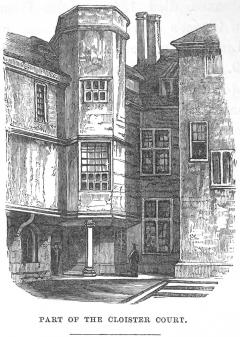

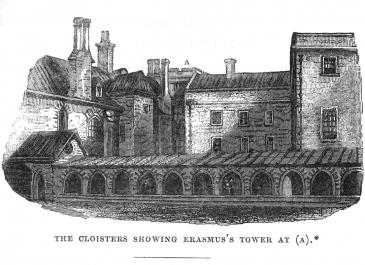

Two small woodcuts of Cloister Court first published in the same volume as the print above, ca. 1837–42.

Two small woodcuts of Cloister Court first published in the same volume as the print above, ca. 1837–42.

Left: looking to the north-east corner.

Right: looking to the north-west corner.

This view of Cloister Court is by Rock & Co, No 2430, dated 1 May 1854, titled Erasmus’ Tower, Queen’s College Cambridge, first published in The Tourist’s Souvenir of Cambridge, 1855.

This view of Cloister Court is by Rock & Co, No 2430, dated 1 May 1854, titled Erasmus’ Tower, Queen’s College Cambridge, first published in The Tourist’s Souvenir of Cambridge, 1855.

The louvre inserted by Dawkes in 1846 can be seen on the roof of the Hall.

In Browne & Seltman, plate 48, this print is mis-credited to L. May

, the authors having mistaken the date for a name.

This photograph is thought to have been taken by Robert Cade in 1857: it occurs in an album where other photos of similar appearance bear his signature, or part of it. Robert Cade, of Ipswich, is known to have visited Cambridge in 1857, and his Cambridge photographs began appearing at exhibitions in 1858.

This photograph is thought to have been taken by Robert Cade in 1857: it occurs in an album where other photos of similar appearance bear his signature, or part of it. Robert Cade, of Ipswich, is known to have visited Cambridge in 1857, and his Cambridge photographs began appearing at exhibitions in 1858.

This view shows one of the side windows of the Hall in an intermediate state in which they existed for only a short period. The tracery added by Dawkes in 1846 can be seen: this tracery would last only until 1857/58.

The cupola for the dinner bell can be seen as re-designed by Dawkes.

The strangely truncated windows of staircase I can still be seen.

The doors visible under the window lead to steps down to cellars under the Hall.

Another photograph by Robert Cade in 1857, of the riverside building on the western side of Cloister Court. The central archway leads to the Mathematical Bridge. This building is the oldest standing on the River Cam, and the second oldest in College, after Old Court.

Another photograph by Robert Cade in 1857, of the riverside building on the western side of Cloister Court. The central archway leads to the Mathematical Bridge. This building is the oldest standing on the River Cam, and the second oldest in College, after Old Court.

This building is discussed further in a separate page.

Note that the cloister arches on the ground floor of this building (except the central arch) are of three chamfered orders, whereas the arches of the side cloisters are simpler, of two chamfered orders.

A photograph of Cloister Court some short time after 1859.

A photograph of Cloister Court some short time after 1859.

Much has changed since the 1857 photograph above: in 1857/58 the side windows were heightened and new tracery installed to the design of John Johnson, architect. Then in 1858/59 new stained glass by Hardman of Birmingham was installed in the north (left) window, but not in the south (right) window, which retained its clear glass in this photo, and must have had stained glass installed slightly later. The truncated-height windows on staircase I have been restored to full height, and the sills raised by about three courses of bricks. Parapets have been added along the entire eastern elevation.

A wide-angle photograph of Cloister Court, probably taken in the 1860s. The stained glass of the south (right) side window of Hall looks very new and regular, whereas the glass in the north (left) window has already warped slightly with age.

A wide-angle photograph of Cloister Court, probably taken in the 1860s. The stained glass of the south (right) side window of Hall looks very new and regular, whereas the glass in the north (left) window has already warped slightly with age.

The next buildings to arrive in Cloister Court after the riverside building (extreme right) were the north and south cloister walks: the complete south cloister can be seen here. The cloister walks were built definitely later than the riverside building, as can be seen by inspecting the fabric where they meet. Willis & Clark, on the basis of circumstantial evidence, suggest a date of around 1494/5.[AHUC, Willis & Clark, Vol. 2, pp. 14–15]

The arches of the riverside cloisters are of three chamfered orders, whereas the arches of the side cloisters are of only two orders: except the centre arch of the eleven on the south side, which has a vestigial third order, and might have once been a full height central opening for entry into the court, just as there are central openings in the west and north cloisters.

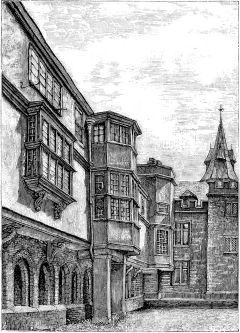

Two wood-cuts of Cloister Court, engraved by F. Anderson (monogram at bottom left corner), possibly drawn by John O’Connor. [AHUC, Vol. 1, Preface p. xxviii]

Two wood-cuts of Cloister Court, engraved by F. Anderson (monogram at bottom left corner), possibly drawn by John O’Connor. [AHUC, Vol. 1, Preface p. xxviii]

They were first published in the Architectural History of the University of Cambridge, by Willis & Clarke, 1886, Vol. 2, pp. 29 & 16, but possibly drawn earlier.

Left: Long Gallery exterior, SCR, staircase to President’s Study.

Right: Porch to Hall, south cloister, staircase ‘I’, Erasmus’s Tower.

A parallax-corrected photograph of Cloister Court, thought to date from 1891.

A parallax-corrected photograph of Cloister Court, thought to date from 1891.

The Long Gallery, seen here on the left, was built on top of the northern cloister walkway at some point in the 16th century. It is discussed further in a separate page.

Over the Long Gallery, there are only the two original chimneys. A third chimney was to be added around 1897, to serve a new boilerhouse which was created to heat the President’s Lodge.

A watercolour of Cloister Court, by William Matthison (1853–1926), first published in Cambridge, by Mildred Anna Rosalie Tuker, 1907. This book was published to meet the demand for colour illustrations in a guide-book, before mass reproduction of colour photography became possible. Matthison, who had a reputation for architectural accuracy, was commissioned in 1904 to provide the illustrations, and painted 77 watercolours of Cambridge for this book.

A watercolour of Cloister Court, by William Matthison (1853–1926), first published in Cambridge, by Mildred Anna Rosalie Tuker, 1907. This book was published to meet the demand for colour illustrations in a guide-book, before mass reproduction of colour photography became possible. Matthison, who had a reputation for architectural accuracy, was commissioned in 1904 to provide the illustrations, and painted 77 watercolours of Cambridge for this book.

By comparison with the previous photo of 1891, a third chimney can be seen over the Long Gallery, serving the boilerhouse below, added around 1897. The new chimney is the one on the left of the original two.

The Long Gallery is shown in its condition before the plaster was removed in 1911.

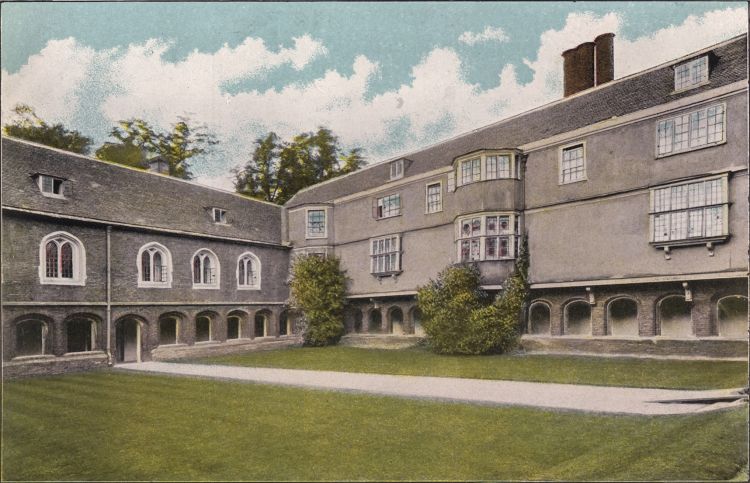

Another way of producing coloured illustrations was to apply artificial colour to monochrome photographs. This view was first published in Pictures in Colour of Cambridge : With its University and Colleges, with descriptive notes by “A Resident Trinity M.A.”, undated, but thought to have been published in 1906, by Jarrold.

Another way of producing coloured illustrations was to apply artificial colour to monochrome photographs. This view was first published in Pictures in Colour of Cambridge : With its University and Colleges, with descriptive notes by “A Resident Trinity M.A.”, undated, but thought to have been published in 1906, by Jarrold.

Queens’ College, Cloisters Court. — Margaret, wife of Henry VI., and Elizabeth, wife of Edward IV., were the origin of the name bourne by this College. In the view is seen the second court, with its quaint small cloisters, which slope down to the river, and three oriel windows of the long gallery room, of which another example is at St. John’s. Beyond this court a curious timber arch crosses the river to a garden, with the only clear extant example of the bakehouse and brewhouse, once normal limbs of the Collegiate organism. At Queens’ were Fisher (the Romish martyr), Erasmus (the noted Grecian and reformer), and Fuller of “Church History” fame.

In this image, the artificial colouring seems to have omitted all the buildings apart from the chimneys.

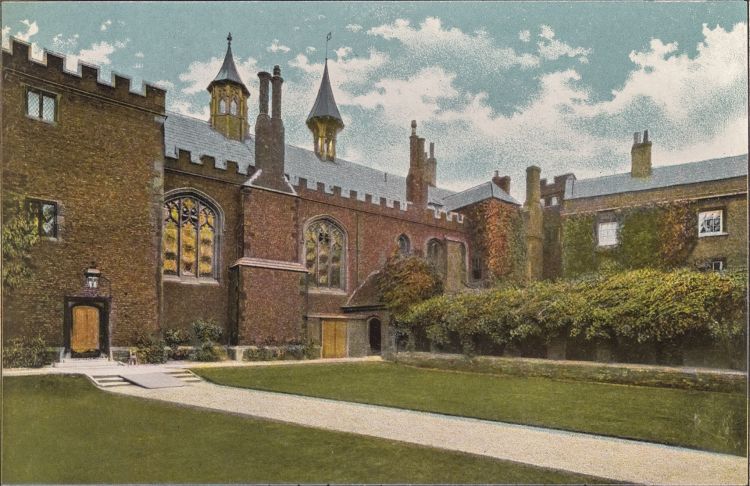

A second image from the same book as the one previous.

A second image from the same book as the one previous.

Queens’ College, Erasmus Tower. — In the right centre of this illustration is seen a small battlemented tower, the top storey of which was in all probability used as a study by Erasmus. Similar turrets are at each of the four angles of the First Court. Erasmus had amassed stores of learning at many European Universities before he came to England; in 1489 he visited Oxford, and later for some years was Lady Margaret Professor of Divinity at Cambridge. He was attracted to Queens’ College especially by the fact that his friend and fellow-worker, Bishop Fisher, was at that time Master. He gave to the study of Greek, then almost extinct, an impulse that has not yet been lost.

A photograph of Cloister Court in 1959.

A photograph of Cloister Court in 1959.

The embattled parapets were removed in 1909 when the Hall roof was repaired.[The Dial, Mich. 1909] It appears that the top of the staircase to the President’s Study was rebuilt at the same time.

The external appearance of the Long Gallery changed in 1911.

The inappropriate louvre of 1846 was removed from the Hall in 1950/51 and the roof patched. [Queens’ College 1950–51, p. 6]

The central path of the court was paved for the first time in 1951/52. [Queens’ College 1951–52, p. 8]

At some point in the late 20th century, the steps at the east end of the central path were replaced by a slope.

Further reading

1886: The Architectural History of the University of Cambridge, by Robert Willis and John Willis Clark, Vol. 2; pp. 13–15. (OCLC 6104300)

1959: An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the City of Cambridge, by the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (England), Part II, pp. 174–. (online version)