The portrait of her shown here is probably a multiple-generation copy of one taken from life. The College has several versions in differing states. She is shown posed in the high fashion of the day, with strained back hair and a partial veil.

Queens’ had been founded first by Margaret, a Lancastrian queen, then refounded by Elizabeth, a Yorkist queen, thus surviving the Wars of the Roses.

The connection with her is remembered in the name Woodville Room given to the MCR at Queens’.

The Arms of Elizabeth Woodville

Quarterly of six:

Quarterly of six:

- Argent, a lion rampant double-queued gules crowned or (for Luxembourg);

- Quarterly,

i and iv, Gules, an estoile argent;

ii and iii, France Ancient (for Baux); - Barry of ten argent and azure, a lion rampant gules (for Cyprus);

- Gules, three bends argent, on a chief per fess argent and or a rose gules (for Ursins);

- Gules, three pales vair, on a chief or a label of five points azure (for St Pol);

- Argent, a fess and a canton conjoined gules (for Woodville).

The first five quarterings are taken from her mother, Jacquetta of Luxembourg, daughter of Peter, Count of St Pol.

Spelling of Woodville

The spelling Woodville is relatively modern, appearing about the time of Shakespeare, and would never have been used in her own lifetime. The spelling of her maiden surname was highly variable. Her brother's surname was spelled Wydeville by the printer Caxton. On her own tomb, her name is spelled Widvile.

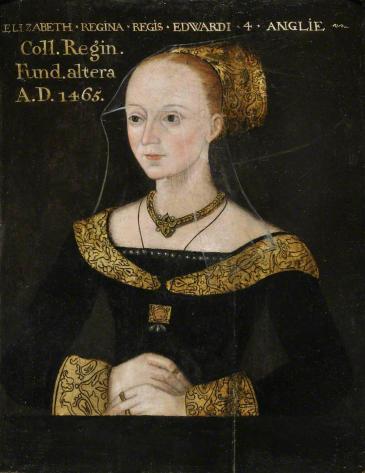

Images of Elizabeth Woodville

Left, © RCIN 406785;

Painted around 1513-30.

Even this earliest known version was painted after Elizabeth’s death, but it is possible that it was a copy of a likeness taken during her life. Note the design of the hat, which had a long extension forward to the centre of her forehead (a) to attach the wires which supported the veil, and (b) to be a counter-balance for the weight of the hat behind her head: many later copies lose this detail. The ear is unrealistically high, and the shoulders are narrow. This version has been badly over-painted so that much detail has been lost, including the veil.

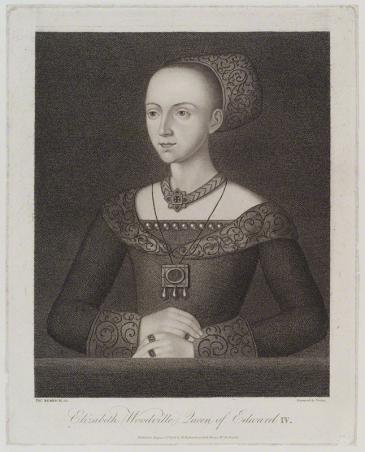

Right, © RCIN 404744;

Probably late 16th century.

404744 is missing a ring from one finger. The ring on the little finger is one joint higher than in any other version. The necklace brooch has a square-set centre-piece, where 406785 has it aligned diamond fashion. The chest brooch is small, the beads hanging from it are crowded, it is without a centre jewel and missing much detail. Like many other late copies, it has broader shoulders than the earlier copies.

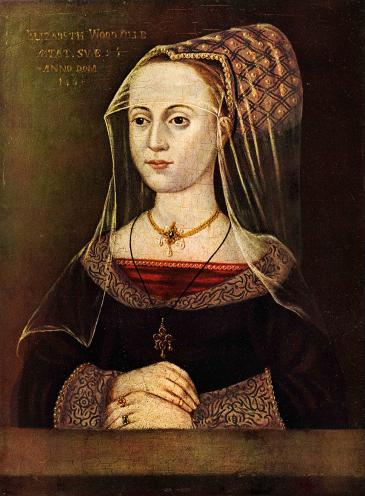

Queens’ College Collection

Queens’ College Collection

Left, QC portrait 130.

QC 130 shares with RCIN 404744 the square-set centre-piece of the necklace brooch, and the small chest brooch with crowded beads. But the shoulder decorations are not mirror-images, neither are the cuffs. The primary plant-like motif of 404744 is drawn upside-down on her left shoulder, the right shoulder is quite different. The right cuff has a similar design to that of QC 88, the left cuff has the same design a little shifted, rather than mirror-image. Only three fingers of her right hand are visible, and the ring has been shifted from missing small finger to fore-finger.

Right, QC portrait 88.

Judging by the patterns on the shoulders and cuffs, QC 88 shares a common ancestry with RCIN 404744 above, but they each differ from RCIN 406785 in ways that the other does not, so it is unlikely that one is a copy of the other. In the necklace brooch, QC 88 has inverted jewel colours, and the centre-piece is set diamond-fashion. It has a full-size chest brooch, and a full set of rings.

Left, QC portrait 53.

Left, QC portrait 53.

The centre-piece of the necklace jewel is set diamond-fashion. The chest brooch is full-size. The shoulders and cuffs are mirror-images, but the primary plant-like motif is drawn on both shoulders upside-down compared with QC 88 and 404744. Similar to the Ripon Cathedral Deanery version, below. The arrangement of the hands here is different from any other version, and less authentic.

Right, QC portrait 99.

Different in character from the other versions: jewellery and rings are more crudely drawn. The patterns of the shoulders and cuffs are unique to this painted version, but identical to the Kerrich/Facius print below. This makes me wonder whether this version was in fact painted by Kerrich around 1800.

Left: print engraved by William Nelson Gardiner, published by Edward Harding 1790.

Left: print engraved by William Nelson Gardiner, published by Edward Harding 1790.

In the decoration of shoulders and cuffs, this print resembles QC 53, above, more than any of the others, but the hands resemble QC 130. This image © National Portrait Gallery D23803, Elizabeth Woodville. Licensed CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

Right: print drawn by Thomas Kerrich, engraved by Georg Siegmund Facius, published by William Richardson 1803.

This print and QC 99, above, share a unique design of fabric decoration, unlike any other. This image © National Portrait Gallery D19617, Elizabeth Woodville. Licensed CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

Apparently a copy deriving from RCIN 406785, from the period before 406785 was so badly over-painted. This version might, therefore, be the closest we can now approach to the original appearance of the portrait. Compared with 406785, it shares the high ear, narrow shoulders, and hat design, but this version has lost detail and colour from the two brooches. The patterns on the shoulders and cuffs are similar to those in the Shaw version below. Image © Ashmolean Museum, permitted non-commercial use.

Right: Dunham Massey.

Apparently a copy of RCIN 406785, or of the Ashmolean copy. Formerly in the collection of the Grey family, Earls of Stamford, who were descendants of Elizabeth Woodville by her first marriage to John Grey of Groby. Image © National Trust, permitted non-commercial use.

Left: Ripon Cathedral Deanery

Left: Ripon Cathedral Deanery

Judging by the patterns on the hat, shoulders, and cuffs, this version shares a common ancestry with QC 53 above, although the placement of the hands is more authentic here than in QC 53.

This next portrait (Shaw) raises many questions. Its inscription reads:

This next portrait (Shaw) raises many questions. Its inscription reads:

ELIZABETH WOODVILLE

ÆTAT SUÆ 26

ANNO DOM

1463

The spelling Woodville

is relatively modern, and would not have been used in her lifetime. The date 1463 lies between the death in 1461 of her first husband Sir John Grey of Groby, and her first meeting with King Edward IV, by all accounts. In 1463 she would have been referred to as Lady Grey

, or similar, and not by her maiden name. Nor would her maiden name have been used after she had married the king. Before she had met the king, she would not have had the financial resources to commission a portrait. [When Was Elizabeth Woodville Born?, by Susan Higginbotham]

The portrait itself is very different from all the other versions above. The face is turned further towards the viewer, so that the outline of the nose does not reach as far towards the outline of the cheek. The veil is simplified, just draped over the hat with apparently no need for wires at the back. The two brooches, on the necklace, and on the chest, are radically different: the chest brooch has five jewels in the shape of a crucifix, with three beads suspended below, but not in a straight line. The hat and cuffs have beaded edges. The hat has beads, or pearls, instead of the circular patterns of 406785 and copies. The fabric pattern on the cuffs and shoulders resembles the Ashmolean version more closely than any other.

The former owner of this portrait, William Arthur Shaw, postulated (a) that it was painted in 1463 by John Stratford, appointed by King Edward IV as King’s Painter in 1461, and (b) that all other versions are copies of this one. [The Early English School of Portraiture, by William A. Shaw, in The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 65, No. 379 (Oct., 1934), pp. 171–184] This opinion, for which he presented no evidence, no longer seems to be supported. This portrait is known only by a 1911 colour photograph [An Early English Pre-Holbein School of Portraiture, by William Arthur Shaw, in The Connoisseur: an illustrated magazine for collectors, Vol. XXXI, Sept. 1911, pp. 72–81.] and a monochrome photograph in the 1934 article above. The portrait has never been reported by anyone other than Dr Shaw, and its present whereabouts are unknown.

A likeness of Elizabeth Woodville in the stained glass windows at the martyrdom or north cross chapel of Canterbury Cathedral. This glass has been dated to 1482, and might be the work of John Prudde, the King’s glazier. [Elizabeth Woodville: Mother of the Princes in the Tower, by David Baldwin, p. 145]

A likeness of Elizabeth Woodville in the stained glass windows at the martyrdom or north cross chapel of Canterbury Cathedral. This glass has been dated to 1482, and might be the work of John Prudde, the King’s glazier. [Elizabeth Woodville: Mother of the Princes in the Tower, by David Baldwin, p. 145]

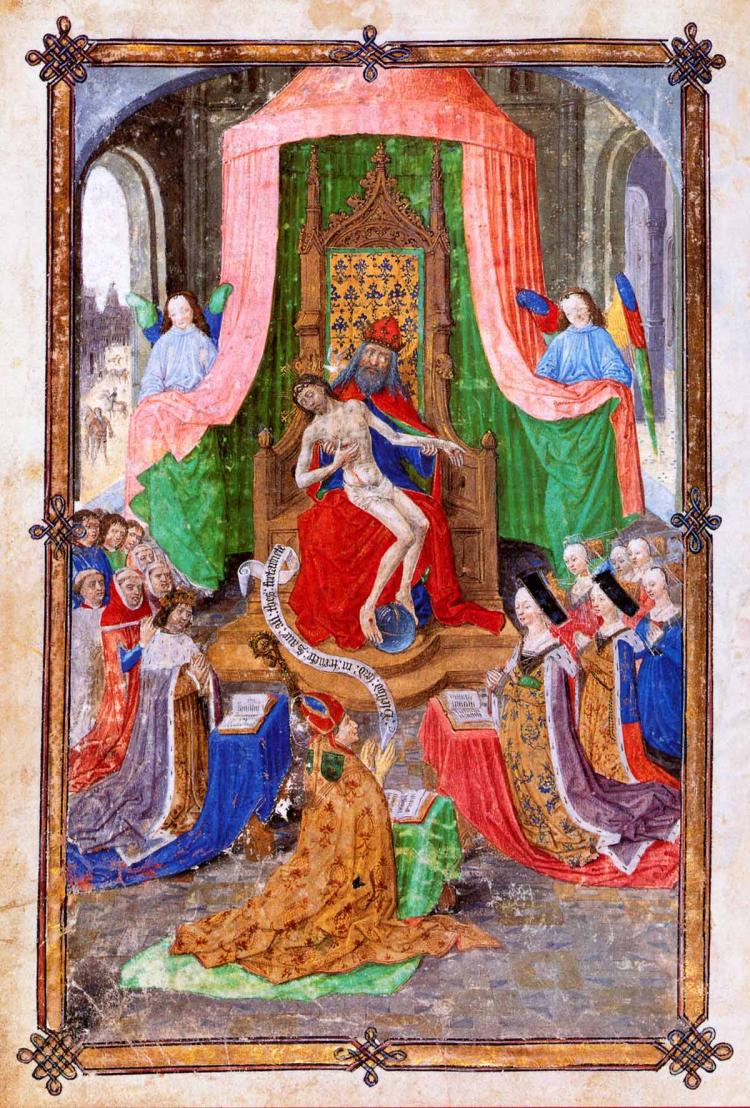

A devotional image from the Register of the Fraternity or Guild of the Holy and Undivided Trinity and Blessed Virgin Mary in the Parish Church of Luton, showing Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville praying before the Holy Trinity, led by Thomas Rotherham, Bishop of Lincoln, who prays:

A devotional image from the Register of the Fraternity or Guild of the Holy and Undivided Trinity and Blessed Virgin Mary in the Parish Church of Luton, showing Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville praying before the Holy Trinity, led by Thomas Rotherham, Bishop of Lincoln, who prays: Blessed God in Trinity, save all this fraternity

. Dated ca. 1474. (The Holy Spirit is depicted as a semi-transparent white bird).

Now we pass from contemporary images to retrospective fictional ones:

This imaginary Elizabeth Woodville was published in 1714 by Thomas Bakewell as part of a set: Fundatores Collegiorum Cantabrigiensium consisting of mezzotints by John Faber, Senior, purporting to represent the founders of each college. The inscription reads:

This imaginary Elizabeth Woodville was published in 1714 by Thomas Bakewell as part of a set: Fundatores Collegiorum Cantabrigiensium consisting of mezzotints by John Faber, Senior, purporting to represent the founders of each college. The inscription reads:

ELISABETHA Edwardi IIII Uxor.

Coll: Regina Cantab: fund.x altera A.o D.ni 1456.

Hanc Effigiem Rev:do Viro Hen: James S.T.P. Regio

et istius Coll. Presidenti Humillime Dicat J: Faber.

Elisabeth, Wife of Edward IV, second Foundress of Queen’s Coll. Cambridge AD 1456 [sic]. J. Faber most humbly offers this image to the Revd Henry James, Regius Professor of Divinity and President of that College.

In fact, Elizabeth became second foundress in 1465, not 1456.

This image is © National Portrait Gallery D16278, Elizabeth Woodville by John Faber Sr. Licensed CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

A strange not-quite-exact mirror image of the above, presumably of the same period.

A strange not-quite-exact mirror image of the above, presumably of the same period.

This image is © The Royal Collection RCIN 600627, permitted non-commercial use.

A three-quarter length re-imagined portrait of Elizabeth Woodville, by Thomas Hudson, 1766, based on the other half-length portraits of her already in college. It was designed to be a large portrait behind High Table on the classical panelling of the dining hall.

A three-quarter length re-imagined portrait of Elizabeth Woodville, by Thomas Hudson, 1766, based on the other half-length portraits of her already in college. It was designed to be a large portrait behind High Table on the classical panelling of the dining hall.

This portrait was donated to the college by George Harry Grey, Fellow-Commoner 1755–58, and later the 5th Earl of Stamford, who was a direct descendent of her by her first marriage to John Grey of Groby. His two younger brothers donated portraits at the same time, to make a matching set of three.

The timing of the donation might have been prompted by the three-hundredth anniversary of Elizabeth becoming foundress by succession in 1465.

Lady Grey, from The Shakespeare Gallery: containing the principal female characters in the plays of the great poet, by Charles Heath, ca 1836.

Lady Grey, from The Shakespeare Gallery: containing the principal female characters in the plays of the great poet, by Charles Heath, ca 1836.

Drawn by Philip Francis Stephanoff, engraved by Hall(?) or B. Holl(?).

Lady Grey, from The Heroines of Shakespeare: comprising the principal female characters in the plays of the great poet, by Charles Heath, 1848.

Lady Grey, from The Heroines of Shakespeare: comprising the principal female characters in the plays of the great poet, by Charles Heath, 1848.

Drawn by John William Wright and engraved by B. Eyles.

Elizabeth Woodville, Queen of Edward 4th, published 1851 in Biographical Sketches of the Queens of Great Britain from the Norman Conquest to the Reign of Victoria: or, Royal book of beauty, by Mary Howitt.

Elizabeth Woodville, Queen of Edward 4th, published 1851 in Biographical Sketches of the Queens of Great Britain from the Norman Conquest to the Reign of Victoria: or, Royal book of beauty, by Mary Howitt.

Drawn by John William Wright and engraved by Henry Collier Austin.

Elizabeth Woodville, by George Perfect Harding, published by Henry Colburn 1851. This is clearly just a re-working of Harding’s uncle Edward’s print of 1790 (above).

Elizabeth Woodville, by George Perfect Harding, published by Henry Colburn 1851. This is clearly just a re-working of Harding’s uncle Edward’s print of 1790 (above).

Used as an illustration in the 4th edition of Lives of the Queens of England, from the Norman Conquest, by Agnes Strickland, Vol 2, 1854.