The First Forty Years

Andrew Dokett

The prime mover for the founding and early development of the college, now known as Queens’ College, was Andrew Dokett.

Nothing is reliably known about the origins of Andrew Dokett, and what little has been published is unsubstantiated (to put it politely). There are several pedigrees published on genealogical sites on the web claiming to show him as having married, with descendants. As a priest in the pre-reformation church, he would never have married or had children, so the veracity of such material is in doubt.

Early histories also claimed that Andrew Dokett was a Minorite, or Franciscan friar.[1622a, 1622b, 1655] Had that been true, Dokett would not have been able to rise to the positions in the hierarchy of the church that he did in fact later achieve.[1726 pp. 205–6]

The first reliable evidence of his existence dates from the late 1430s, when it emerged that an Andrew Dokett was the vicar of St Botolph’s parish in the town of Cambridge.

On the right is a sketch of the monumental brass of Andrew Dokett, as seen in the chapel by the 18th century antiquarian William Cole. The brass no longer exists, and might not have been a true likeness in any case, as the college accounts suggest that it was made in 1563.

St Botolph’s Parish Church

St Botolph’s is one of the ancient parishes of Cambridge. The location of the church, dedicated to the patron saint of travellers, is on the eastern side of Trumpington Street, roughly 50 yards inside the southern gate of the medieval town. That gate was located near the present junction of Mill Lane and Pembroke Street. The present church building dates from the 14th century, with later alterations and additions, including the tower in the 15th century. Queens’ College, and all its predecessor institutions, lie wholly within the parish of St Botolph.

St Botolph’s is one of the ancient parishes of Cambridge. The location of the church, dedicated to the patron saint of travellers, is on the eastern side of Trumpington Street, roughly 50 yards inside the southern gate of the medieval town. That gate was located near the present junction of Mill Lane and Pembroke Street. The present church building dates from the 14th century, with later alterations and additions, including the tower in the 15th century. Queens’ College, and all its predecessor institutions, lie wholly within the parish of St Botolph.

Andrew Dokett appears to have become vicar of St Botolph’s around 1436–39, although no record still exists of his appointment. After a complicated legal case, Dokett was elevated from vicar to rector sometime before 1444. After further complicated negotiations, in 1459 he also purchased the advowson: the right in perpetuity to select and present future rectors to the parish. He gave this advowson to the college.[1922 pp. 98–102]

Hostels

Before the colleges were of a number and size to accommodate students, many students enrolled at the University of Cambridge sought accommodation in various “hostels” in the town. These hostels served a similar purpose to Halls of Residence in a modern university (but much smaller): they provided accommodation, meals, and were subject to university discipline. Many had a transitory existence: there are records of up to 136 of these hostels through the ages (but not all at the same time), and maybe more of which no records survive. Most of the hostels disappeared or closed before the middle of the 16th century. Some hostels evolved into, or were absorbed by, later colleges.[1924]

St Bernard’s Hostel

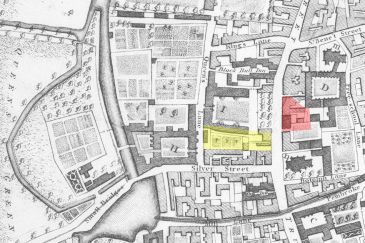

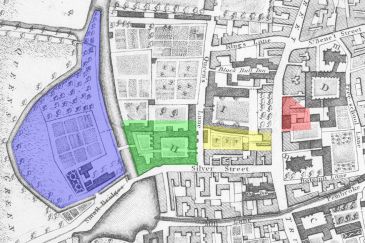

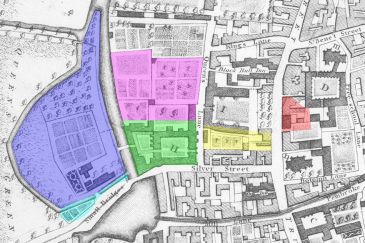

Andrew Dokett was the owner of St Bernard’s Hostel, on the east side of Trumpington Street, between the Old Court of Corpus Christi College on the north, and, on the south, not quite as far as St Botolph’s Church, where Dokett was the vicar and, later, rector. The land on which St Bernard’s Hostel was built is now occupied by part of the New Court of Corpus Christi College. We have no record of when St Bernard’s Hostel came into being. It appears to have been quite well-appointed, having a hall, gallery, and chapel of its own. [1886 v.1 p.248] [1924 pp. 63–4] The approximate location of St Bernard’s Hostel is marked in pink on this plan: its exact size and shape are not known. [1886 v.4 10]

Andrew Dokett was the owner of St Bernard’s Hostel, on the east side of Trumpington Street, between the Old Court of Corpus Christi College on the north, and, on the south, not quite as far as St Botolph’s Church, where Dokett was the vicar and, later, rector. The land on which St Bernard’s Hostel was built is now occupied by part of the New Court of Corpus Christi College. We have no record of when St Bernard’s Hostel came into being. It appears to have been quite well-appointed, having a hall, gallery, and chapel of its own. [1886 v.1 p.248] [1924 pp. 63–4] The approximate location of St Bernard’s Hostel is marked in pink on this plan: its exact size and shape are not known. [1886 v.4 10]

Colleges

The principal differences between a “college” and a “hostel” are that:

- colleges are perpetual corporate bodies, founded by royal charter, and self-governing under conditions stipulated in the charter and a set of statutes;

- colleges are endowed bodies, with capital resources (usually land, originally) that generate income;

- that income is used to subsidise the students, by scholarships and bursaries, and to employ teachers (“Fellows”);

- thus colleges had a role in teaching, which hostels had never had.

The first college to be founded in Cambridge was Peterhouse, in 1284. By 1352, eight colleges had been founded, but there was then a long period with no new foundations until King’s College in 1441. In the early days, it was quite possible for a student to be a member of a college for tuition, but be accommodated in a hostel.

St Bernard’s College, first foundation

Dokett had ambitious plans to create a college in Cambridge, as an evolution from his St Bernard’s Hostel. At that time, there were only nine colleges in existence, and it had only been a few years since the King (Henry VI), with all his wealth and power, had founded King’s College in 1441. How could a parish priest compete in a venture of such magnitude? With the help of donations from his parishioners, and other wealthy Cambridge residents, he was able to acquire a plot of land, described as 277½ feet long east-west, from the [present] Trumpington Street to the [present] Queens’ Lane, and 72 to 75 feet wide north-south. [1867 pp.3–4] The boundaries and shape of the site are not known exactly, but the site was roughly in the area shaded yellow in the plan. On the west side of Trumpington Street, its frontage was probably roughly where Sam Smiley’s shop or the Woodlark Building of St Catharine’s College now are. On Queens’ Lane, the site was roughly where the current Fellows’ car park of St Catharine’s College now is, plus about half the width of the college buildings on the north side of the car park.

Dokett had ambitious plans to create a college in Cambridge, as an evolution from his St Bernard’s Hostel. At that time, there were only nine colleges in existence, and it had only been a few years since the King (Henry VI), with all his wealth and power, had founded King’s College in 1441. How could a parish priest compete in a venture of such magnitude? With the help of donations from his parishioners, and other wealthy Cambridge residents, he was able to acquire a plot of land, described as 277½ feet long east-west, from the [present] Trumpington Street to the [present] Queens’ Lane, and 72 to 75 feet wide north-south. [1867 pp.3–4] The boundaries and shape of the site are not known exactly, but the site was roughly in the area shaded yellow in the plan. On the west side of Trumpington Street, its frontage was probably roughly where Sam Smiley’s shop or the Woodlark Building of St Catharine’s College now are. On Queens’ Lane, the site was roughly where the current Fellows’ car park of St Catharine’s College now is, plus about half the width of the college buildings on the north side of the car park.

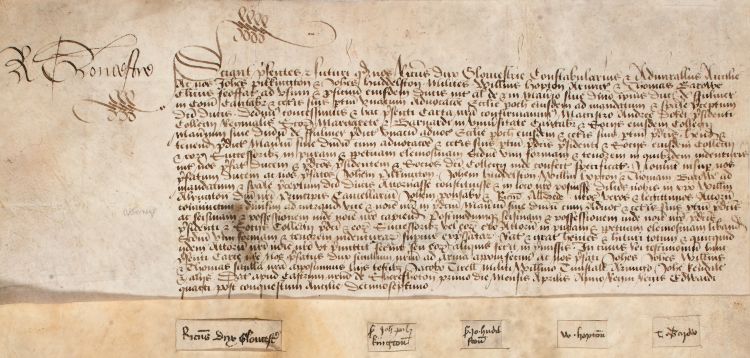

On 3rd December 1446, King Henry VI issued a charter for the foundation of St Bernard’s College on the above site [Cal.Ch.R. 25–26 Henry VI No. 37, misdated 1447 May 19]. The charter also passed to St Bernard’s College ownership of the land on which St Bernard’s Hostel was built. Andrew Dokett was named as President, and four Fellows were named. Apart from the enrolment of this charter, no further record of this first St Bernard’s College survives.

St Bernard’s College, second foundation

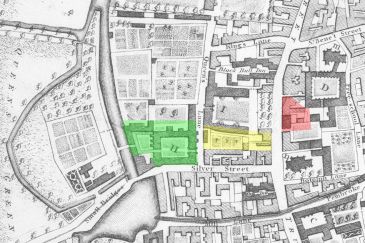

In July 1447, the college acquired a much larger site, between the present Queens’ Lane (on the east), the river Cam (on the west), Small Bridges Street (on the south) and the Carmelite Monastery (on the north). This new land became the site of the present Old Court and Cloister Court, shaded green in the plan. The south-west corner on Small Bridges Street beside the river at first remained occupied by tenements and gardens owned by others, which were later acquired piecemeal by the college, and eventually became Pump Court.

In July 1447, the college acquired a much larger site, between the present Queens’ Lane (on the east), the river Cam (on the west), Small Bridges Street (on the south) and the Carmelite Monastery (on the north). This new land became the site of the present Old Court and Cloister Court, shaded green in the plan. The south-west corner on Small Bridges Street beside the river at first remained occupied by tenements and gardens owned by others, which were later acquired piecemeal by the college, and eventually became Pump Court.

The original charter of St Bernard’s College was returned to the King to be cancelled, and on 21st August 1447, the King issued a new charter of foundation for St Bernard’s College, on the newly acquired site, revoking the earlier charter, but also passing into ownership of the new college the land of the first foundation, and the land of St Bernard’s Hostel. [charter enrolment not found] [1867 pp.7–15] The wording of parts of this second foundation charter implies that the King regarded himself as the Founder of the college. The charter was witnessed by an impressive array of grandees of state, some of whom became benefactors of the college.

Preparations for the building of the college (the present Old Court) on the new site must have started soon after.

The Queen’s College (third foundation)

At some time after the second foundation of St Bernard’s College, the Queen (Margaret of Anjou) petitioned the King:

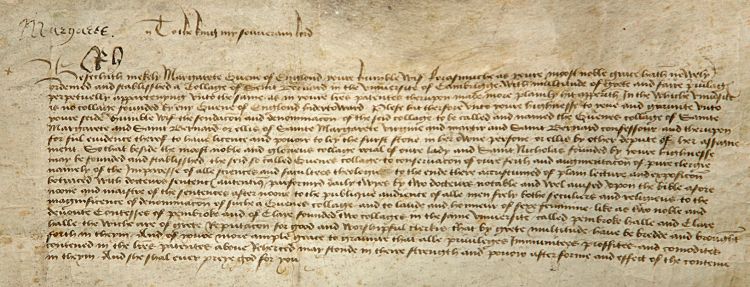

To the King my souverain lord.

[1867 pp.15–16]

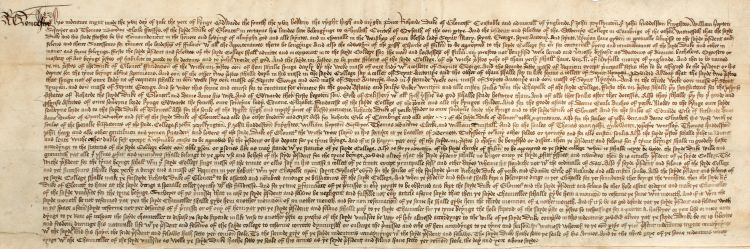

Besecheth mekely Margarete quene of Englond youre humble wif, Forasmuche as youre moost noble grace hath newely ordeined and stablisshed a collage of seint Bernard in the Universite of Cambrigge with multitude of grete and faire privilages perpetuelly appartenyng unto the same as in youre lr︦es patentes therupon made more plainly hit appereth In the whiche universite is no collage founded by eny quene of Englond hidertoward, Plese hit therfore unto youre highnesse to yeve and graunte unto youre seide humble wif the fondacōn and determinacōn of the seid collage to be called and named the Quenes collage of sainte Margerete and saint Bernard, or ellis of sainte Margarete vergine and martir and saint Bernard confessour, and therupon for ful evidence thereof to have licence and pouoir to ley the furst stone in her owne persone or ellis by other depute of her assignement, so that beside the mooste noble and glorieus collage roial of our Lady and saint Nicholas founded by your highnesse may be founded and stablisshed the seid so called Quenes collage to conservacōn of oure feith and augmentacōn of pure clergie namely of the imparesse of alle sciences and facultees theologic.. to the ende there accustumed of plain lecture and exposicōn botraced with docteurs sentence autentiq’ performed daily twyes by two docteurs notable and wel avised upon the bible aforenoone and maistre of the sentences afternoone to the publique audience of alle men frely bothe seculiers and religieus to the magnificence of denominacōn of suche a Quenes collage and to laud and honneure of sexe femenine, like as two noble and devoute contesses of Pembroke and of Clare founded two collages in the same universite called Pembroke halle and Clare halle the wiche are of grete reputacōn for good and worshipful clerkis that by grete multitude have be bredde and brought forth in theym, And of youre more ample grace to graunte that all privileges immunitees profites and comodites conteyned in the lr︦es patentes above reherced may stonde in theire strength and pouoir after forme and effect of the conteine in theym. And she shal ever preye God for you.

The King granted this petition. The college returned the second foundation charter to the King to be revoked. The King by letters patent dated 30 March 1448 granted to Queen Margaret all the lands of St Bernard’s College, and licence to found a college [Cal.Pat.R. 26 Henry VI Pt 2, m.39, pp.143–4] [1867 pp.18–26]. The Queen, by letters patent dated 15 April 1448, founded the Queen’s College of St Margaret and St Bernard, and granted to it all the lands previously awarded to St Bernard’s College. [1867 pp.26–27]

The King granted this petition. The college returned the second foundation charter to the King to be revoked. The King by letters patent dated 30 March 1448 granted to Queen Margaret all the lands of St Bernard’s College, and licence to found a college [Cal.Pat.R. 26 Henry VI Pt 2, m.39, pp.143–4] [1867 pp.18–26]. The Queen, by letters patent dated 15 April 1448, founded the Queen’s College of St Margaret and St Bernard, and granted to it all the lands previously awarded to St Bernard’s College. [1867 pp.26–27]

On the same date, the foundation stone of the Queen’s College was laid at the south-east corner of the chapel by the Queen’s chamberlain, Sir John Wenlock, as her proxy. [1867 pp.41–44]

The day previously, a contract had been issued by the college for the erection of the timber framing of the first phase of the college buildings (the north, east, and part of the south sides), so the building fabric must have been sufficiently advanced to be ready for framing out. [1867 pp.38–39]

No record survives of any direct benefaction from Queen Margaret to the college (although she is cited in the roll of benefactors), but the King authorised a gift of £200 on 4 March 1449, to assist in continuing the building works. [1867 p.62] Two days later, on 6 March, the contract was issued for the timber framing for the second and final phase of the college building (remainder of the south side, and the west side). [1867 pp.39–41]

On 12 December 1454, the chapel was licensed for divine worship by the Bishop of Ely. [1867 pp.41–45]

On 12 January 1459/60, Corpus Christi College sold to Queen’s College a plot of land on Small Bridges Street [Silver Street] which was to become the site of Andrew Dokett’s almshouses. [1867 p.68]

[In order to keep the main history as clear as possible, most records of subsqeuent benefactions have been removed to a separate page at: Early Benefactions]

The Second Queen

By the early 1450s, the declining health of an already weak and unpopular King Henry VI was a contributory factor leading to the outbreak of a civil war of succession, retrospectively known as the “War of the Roses”, between two cadet branches of the Plantagenet dynasty: the “House of Lancaster” (to which Henry VI belonged), and the “House of York”. This struggle presumably brought to an end any further support from Henry or Margaret for the as-yet uncompleted college. King Henry VI and Queen Margaret were deposed in 1461 when the Yorkist Edward IV was crowned King.

In May 1464, Edward IV married Elizabeth Woodville, who was eventually crowned Queen in May 1465. (Elizabeth had been previously married to Sir John Grey of Groby, who was killed in battle 1461, and had two sons by that marriage).

In May 1464, Edward IV married Elizabeth Woodville, who was eventually crowned Queen in May 1465. (Elizabeth had been previously married to Sir John Grey of Groby, who was killed in battle 1461, and had two sons by that marriage).

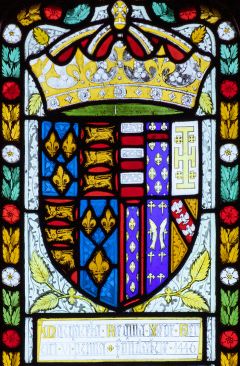

Two months earlier, in March 1465, King Edward IV by letters patent granted to the college a licence allowing the college to own permanent assets from which the annual income did not exceed £200 per year.[Cal.Pat.R. 5 Edward IV Pt 3, m.22 & 21, p.495] [1867 pp.70–1] In that deed, he describes the college quod de patronatu Elizabeth regine Anglie consortis nostre carissime existit

(which exists by the patronage of Elizabeth, Queen of England, our beloved consort). It is this reference that has been taken, in early histories, to imply that Queen Elizabeth “re-founded” the college in 1465. No record survives of any explicit act of re-foundation. No record survives of any direct benefaction from Queen Elizabeth herself, although she is cited in the roll of benefactors, along with other members of the House of York, details of whose benefactions also do not survive. [A curious feature of this 1465 licence is that the 1448 deed of foundation had already set the limit on permanent assets at £200 income per year, so this 1465 licence achieved no advance on the pre-existing situation.]

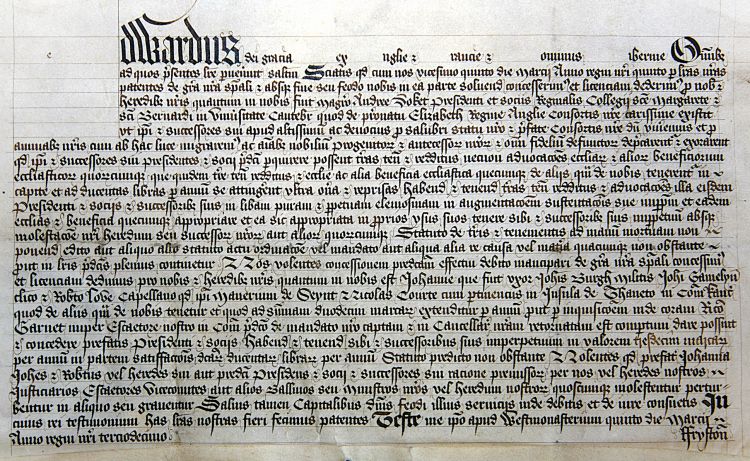

On 1473 March 5, the king granted a licence allowing Lady Joan Burgh to donate the estate of St Nicholas Court in the Isle of Thanet to the college in order to found a fellowship after her death [Cal.Pat.R. 13 Edw IV Pt 1, m.10, p.394] [1867 pp.81–3].

On 1473 March 5, the king granted a licence allowing Lady Joan Burgh to donate the estate of St Nicholas Court in the Isle of Thanet to the college in order to found a fellowship after her death [Cal.Pat.R. 13 Edw IV Pt 1, m.10, p.394] [1867 pp.81–3].

The estate was re-granted to her for her lifetime, and returned to the college after her death in ca.1493.

In this deed, the college is again described as quod de patronatu Elizabeth Regine Anglie consortis nostre carissime existit

(which exists by the patronage of Elizabeth, Queen of England, our beloved consort).

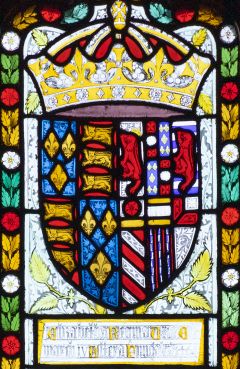

In March 1475, Queen Elizabeth, by letters patent, granted to the college its earliest documented set of statutes, in the preamble to which she described herself as vera fundatrix

(true foundress). [1867 p.84] The frequently quoted phrase describing Queen Elizabeth as True foundress by right of succession

was never used by herself or by the King. This phrase first appeared as uti jure successionis vera fundatrix

in an early account of the foundation of the college, held in the college archives, probably written after the death of Andrew Dokett in 1484, and reproduced in many subsequent histories. [1867 pp.71–2] The phrase reflects the contemporary view of the natural succession of royal patronage.

In October 1475, the College purchased from the Mayor and Burgesses of Cambridge (who had been mandated to sell by letters from the King, Queen, and Prince) the site west of the river, as far as the stream running down from Newnham Mill [now Queens’ Ditch]. This land, shaded blue in the plan, is now the site of Fisher Building, Cripps Court, Lyon Court, and the Grove.

In October 1475, the College purchased from the Mayor and Burgesses of Cambridge (who had been mandated to sell by letters from the King, Queen, and Prince) the site west of the river, as far as the stream running down from Newnham Mill [now Queens’ Ditch]. This land, shaded blue in the plan, is now the site of Fisher Building, Cripps Court, Lyon Court, and the Grove.

As part of the purchase agreement, the college was obligated, at its cost, to construct an east-west watercourse to act as the southern boundary of the land (which thus became an island), to widen the main river to 51 feet, and to extend the road bridge by 12 feet. The college was permitted to erect a bridge across the main river. [1867 pp.85–7]

On 1 April 1477, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, via his feoffees, with the agreement of the King,[Cal.Pat.R. 17 Edw IV Pt 1, m.17 p.34, 1477 April 10] gave the Manor of Fowlmere to the college, to be used in accordance with a later indenture. [1867 pp.87–8]

On 1 April 1477, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, via his feoffees, with the agreement of the King,[Cal.Pat.R. 17 Edw IV Pt 1, m.17 p.34, 1477 April 10] gave the Manor of Fowlmere to the college, to be used in accordance with a later indenture. [1867 pp.87–8]

In 1462, John de Vere, 12th Earl of Oxford, a Lancastrian supporter, had been executed for treason, and his estates, and those of his wife Elizabeth, forfeited to the King, Edward IV. The King granted those forfeited estates to his brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester. One of the estates inherited by Elizabeth, Countess of Oxford, had been the Manor of Fowlmere.

On 17 July 1477 Richard Duke of Gloucester made an indenture (in English) stipulating that the income from the Manor of Fowlmere was to found four new Fellowships. These fellowships were to be known as

On 17 July 1477 Richard Duke of Gloucester made an indenture (in English) stipulating that the income from the Manor of Fowlmere was to found four new Fellowships. These fellowships were to be known as The Four Priests of the Duke of Gloucester’s Foundation

. [1867 pp.89–92]

The Third Queen

King Edward IV died unexpectedly in 1483. His natural successor was his eldest son Edward, a child of 12. But before Edward V could be crowned, the marriage of Edward IV and Elizabeth was officially declared bigamous (on the grounds that Edward had been previously betrothed to another), and thus all their children illegitimate, and not entitled to succeed. Edward IV’s brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester was proclaimed King Richard III, and crowned in July 1483. The two sons of Edward IV and Queen Elizabeth, known as the “Princes in the Tower”, were never seen again.

Earlier, in 1472, Richard had married Anne Neville, who therefore became Queen in 1483, crowned alongside her husband. (Previously, Anne had been married to Prince Edward, the only son and heir of Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou: Edward was killed in 1471).

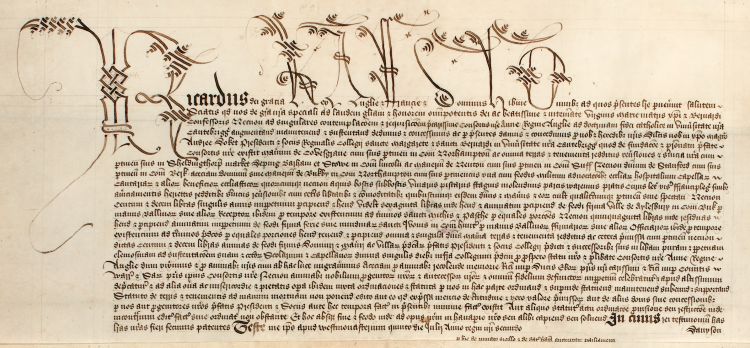

On 25 March 1484, King Richard III, by letters patent,[Cal.Pat.R. 1 Ric III Pt 8, m.3, p.423] granted a licence to the college allowing the college to own permanent assets from which the annual income did not exceed 700 marks (£466 13s 4d), more than double the previous limit of £200 per year. [1867 pp.95–6] This paved the way for a later gift. The preamble of the deed invokes ad singularam contemplationem Anne regine Anglie consortis nostre precarissime

(out of special consideration for Anne, Queen of England, our beloved consort), and describes the college as quod de fundatione et de patronatu prefate consortis nostre existit

(which exists by the foundation and patronage of our aforesaid consort). Thus, just as with Queen Elizabeth previously, Queen Anne is being referred to as foundress and patroness of the college.

On 5 July 1484, King Richard III, by letters patent,[Cal.Pat.R. 2 Ric III Pt 1, m.12, p.477] made a large benefaction to the college, consisting of many estates owned by Queen Anne, plus £110 per year from the income of other estates. The preamble of the deed says

On 5 July 1484, King Richard III, by letters patent,[Cal.Pat.R. 2 Ric III Pt 1, m.12, p.477] made a large benefaction to the college, consisting of many estates owned by Queen Anne, plus £110 per year from the income of other estates. The preamble of the deed says ad singularam contemplationem et requisitionem precarrisime consortis nostre Anne regine Anglie

(out of special consideration for, and by the request of, our beloved consort Anne, Queen of England), and again describes the college as quod de fundatione et de patronatu prefate consortis nostre existit

. [1867 pp.97–100]

By extrapolation from the first half-year accounts of the income actually received, the annual value of this benefaction was £265 15s 8d, very close to the uplift in allowed income granted earlier in March. [1867 p.111] Thus this single benefaction more than doubled the annual income of the college. The fellows appointed from this benefaction were referred to as Fellows of Queen Anne’s Foundation

. Records suggest that there might have been as many as 33 such Fellows on Queen Anne’s Foundation at one point. [1867 p.112]

Queen Anne died 16 March 1485. King Richard III was killed in battle 22 August 1485.

The new King Henry VII reverted all Richard’s and Anne’s gifts, both 1477 and 1484. So the annual income of the college returned to being less than £200 per year.

The new Queen did not involve herself in any benefactions to the college, and no records survive of any subsequent monarch or their consort making any gifts to the college, or regarding themselves as patrons. This marks the end of the period of history when the college received any benefit from royal patronage.

Postscripts

Andrew Dokett resigned as rector of St Botolph’s parish in 1470, but remained President of the college until he died in November 1484. He was buried in the college chapel, but subsequent alterations make it impossible to locate his grave, which might no longer exist. There also used to be a monumental brass of him in the chapel, which was reported in the 18th century as having been worn away.

Margaret of Anjou and Henry VI briefly recovered the throne on 3 October 1470, but were finally defeated, and their only son Prince Edward killed, on 4 May 1471. Henry VI died in captivity in the Tower of London 21 May 1471. Margaret was held in custody pending a ransom. Her father René, Duke of Anjou, could not afford to ransom her, and appears to have persuaded the King of France to pay the ransom in 1475. Margaret died impoverished 25 August 1482 at Dampierre-sur-Loire, near Anjou. She was entombed next to her parents in Angers Cathedral, but her remains were scattered during the French Revolution.

Elizabeth Woodville, as the dowager Queen Elizabeth after the death of her husband, suffered: the execution of her brother Anthony, the execution of her younger son Richard by her first marriage, the loss of her two royal sons Edward and Richard (the “Princes in the Tower”), her marriage being declared bigamous, and her children illegitimate. In 1484 she was stripped of all lands given to her during the reign of Edward IV. Under Henry VII, the legitimacy of her children was reinstated, and her eldest daughter, Elizabeth of York, married Henry VII (a Lancastrian) in 1486, thus symbolically ending the War of the Roses. In 1487 she retired to Bermondsey Abbey, and died there 8 June 1492. She was laid to rest in St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle. From her first marriage, one son Thomas survived, from whom is descended the family Grey of Groby, members of which became benefactors to the college in the 18th century: the three portraits over High Table in the Old Hall were given by them.

Anne Neville died 16 March 1485, and was buried in an unmarked grave in Westminster Abbey. Her only son, Edward of Middleham, died before her.

St Bernard’s Hostel was sold to Corpus Christi College in 1535. At first, it continued in use as a hostel. At some unknown later date, the land became the site of the Dolphin Inn (not to be confused with a better-known Dolphin Inn in Bridge Street, on land which later became the site of Whewell’s Court). In the early 1820s the site was cleared for the erection of New Court.

The land of the first foundation of St Bernard’s College was at first laid out as an orchard or garden, later known as “Tennis-Court Garden”, owing to a tennis court (presumably Real Tennis) being at the eastern end of the garden. [1886 v.2 p.54] In 1638, at the Queens’ Lane end of the garden, a “Stage House” was erected for the storage of the college’s demountable stage. Plans and maps suggest that the college must have acquired, at some unknown date, extra lands adjacent to the site of the first foundation, because (a) the college-owned frontage on Queens’ Lane ended up being roughly double the original 72 feet stated in the charter, and (b) the college-owned site extended south to include some premises along Silver Street, not mentioned in the charter. The southern part of the extended site, bordering Silver Street, including the house on the corner with Queens’ Lane, was leased around 1655 to the University for the University Printer. In 1696 the site of the 1638 “Stage House” was leased to the University, and that building was replaced by the University’s “New Printing House”, which in 1716 was re-purposed as the University School of Anatomy and Chemistry. Strips of land along the northern edge of the site were leased to St Catharine’s College in 1677 and 1729, for their new buildings, and sold to St Catharine’s in 1813, along with the residue of the site which was not at that time leased to the University, for £1372. In 1819 Queens’ sold to the University for £750 the lands leased to the University, and then re-purchased those lands in 1835 for £3500, following the transfer of the University Press to its new site in and around the Pitt Building. [1966 pp.16–35, but see 1991] In 1836 Queens’ sold to St Catharine’s for £7700 the residue of the site still in its possession, including the site of Andrew Dokett’s almshouses on Silver Street. St Catharine’s demolished many buildings on the site [except that the west wall of the Anatomy School survives as the wall of St Catharine’s car park on Queens’ Lane], and built tenements along the Queens’ Lane frontage (opposite Queens’ Old Court), which were demolished in 1875 in order to build a new Master’s Lodge. [1936 p.36] All the lands of the first foundation of St Bernard’s College, plus later adjacent acquisitions, are now in the possession of St Catharine’s College.

The site of the second foundation of St Bernard’s College was nearly trebled in area in 1544 by the acquisition of adjacent land to the north following the dissolution of the Carmelite monastery. The new land, coloured magenta in the plan, was at first laid out as four garden or orchard areas, and a bowling green. Later, Walnut Tree building, Friars Building, the new Chapel, Dokett Building, and Erasmus Building were built on the former Carmelite land. In 1907, a small triangle of land at the north-east corner was sold to King’s College, to make space for their Webb’s Court.

The site of the second foundation of St Bernard’s College was nearly trebled in area in 1544 by the acquisition of adjacent land to the north following the dissolution of the Carmelite monastery. The new land, coloured magenta in the plan, was at first laid out as four garden or orchard areas, and a bowling green. Later, Walnut Tree building, Friars Building, the new Chapel, Dokett Building, and Erasmus Building were built on the former Carmelite land. In 1907, a small triangle of land at the north-east corner was sold to King’s College, to make space for their Webb’s Court.

The land west of the river purchased in 1475 was enlarged to the south (a) at an unknown date after 1813 by the acquisition of the land south of the 1475 ditch, up to the highway boundary, and (b) around 1841 by the infilling of the 1475 ditch. In 1935, following demolition of buildings on that site, there was an exchange of land between the college and the borough council that resulted in the present boundary, following the curve of Fisher Building, thus widening and straightening Silver Street, which had previously been narrow and awkwardly curved.

All lands given to the college as early benefactions were sold in the 20th century: by the second half of the 20th century the college had no agricultural estates at all.

The name of the college remained “The Queen’s College” until the 19th century: see “That Apostrophe”.

References and Further Reading

1572: Catalogus Cancellariorum, Procancellariorum, Procuratorum, ac eorum qui in Achademia Cantabrigiensi ad gradum Doctoratus aspiraverunt, by Archbishop Matthew Parker, pp. 41–2;

1729: Edition as Academiae Historia Cantebrigiensis appended to De Antiquitate Britannicae Ecclesiae …, by Samuel Drake, p. xx.

1574: Historiæ Cantebrigiensis Academiæ ab urbe condita, by John Caius, Liber primus, pp. 70–1; (OCLC 60367592)

1912: Edition within The Works of John Caius, M.D. by Ernest Stewart Roberts, pp. 56–7. (OCLC 11548071)

1622a: Σκελετός Cantabrigiensis, by Richard Parker (unpublished manuscript);

1715: Edition in Latin appended to Leland’s Collecteana, Volume V, edited by Thomas Hearne, pp. 225–8;

1721: Edition in English, in The History and Antiquities of the University of Cambridge, pub. by Thomas Warner, pp. 109–13; [plagiarised by Carter 1753]

1774: Second edition of 1715 Latin version, pp. 225–8.

1622b: The Foundation of the Universitie of Cambridge, by John Scot the Elder; (OCLC 33143124) [tabular form; significant error in account of Queens’]

1634: Another edition, (OCLC 607140137); [corrected, esp. in relation to Queens’, and updated]

1651: Another edition, attrib. Gerard Langbaine, pp. 9–10; (OCLC 265490979) [text from 1634 edition in book form]

1672: Another edition, by John Ivory. (OCLC 49268897) [reverting to tabular form]

1631: Ancient funerall monuments …, by John Weever. (OCLC 84623819)

1655: The History of the University of Cambridge, by Thomas Fuller, Section V, ¶¶31–39, pp. 79–82; (OCLC 752917426)

1655: often bound with The church-history of Britain; (OCLC 13589226)

1840: Edition by James Nichols, pp. 120–3; (OCLC 6928511)

1840: Edition by Marmaduke Prickett and Thomas Wright, pp. 161–6. (OCLC 1977548)

1721: The History and Antiquities of the University of Cambridge : in two parts, pub. by Thomas Warner, pp. 109–13.

[the first part is a translation into English of the fictional Historiola by Nicholas Cantelupe of the foundation of the university; the second part is a translation into English of the 1622 Σκελετός Cantabrigiensis, by Richard Parker: subsequently plagiarised by Carter 1753]

1726: Collectanea Anglo-Minoritica: The Antiquities of the English Franciscans, by Anthony Parkinson, pp. 205–6. (OCLC 6055232) [questions Richard Parker's 1622 account of Andrew Dokett]

1753: The History of the University of Cambridge, from its Original, to the year 1753, by Edmund Carter, pp. 175–96. [plagiarised from the 1721 English edition of Richard Parker’s Σκελετός Cantabrigiensis of 1622]

1823: A Form for the Commemoration of Benefactors, to be used in the Chapel of the College of St Margaret and St Bernard, commonly called Queens’ College, Cambridge, edited by George Cornelius Gorham. [Serves as a catalogue of benefactions. Two copies bound together, the first interleaved, with MS. notes by the editor & W.G. Searle, the second with notes by Searle only, in University Library as Adv.b.94.2 (OCLC 55863359)] (OCLC 55861566)

1862: The Princes of Upper Powys, by George Thomas Orlando Bridgeman, in Collectanea Archæologica: Communications made to the British Archaeological Association, Vol. 1, pp. 79–89, 182–231. (OCLC 8769369) [Sir John Burgh at pp.223 onwards, and 231]

1867: The History of the Queens’ College of St Margaret and St Bernard in the University of Cambridge, by William George Searle, Volume 1, 1446–1560, Cambridge Antiquarian Society Octavo Publications No IX;

1871: Volume 2, 1560–1662, Cambridge Antiquarian Society Octavo Publications No XIII. (Both vols OCLC 3279381)

[In QC Old Library there are (a) a manuscript index for the two published volumes, (b) interleaved editions of the two published volumes with manuscript corrections and updates, (c) preparatory manuscript materials for further volumes].

1876: History of the Princes of South Wales, by George Thomas Orlando Bridgeman. (OCLC 4608036) [Sir John Burgh at pp.275 & 289]

1886: The Architectural History of the University of Cambridge, by Robert Willis and John Willis Clark, Volume 1; (OCLC 6104300)

1886: Volume 2 (incl. Queens’ pp. 1–68 and 770–1);

1886: Volume 3 with Index;

1886: Volume 4 plans.

1898: The Queen’s College of S. Margaret and S. Bernard (1448–1898), by John Willis Clark (OCLC 55865473) [for 450th anniversary]

1899: The Queens’ College of St Margaret and St Bernard in the University of Cambridge, by Joseph Henry Gray; (OCLC 8568413)

1926: New edition, updated. (OCLC 79562186)

1907: The Cambridge Colleges—VIII: The History of Queens’, by Joseph Henry Gray, in The Crown, the Court and County Families Newspaper, 1907 Nov 2nd, pp. 219–20. (OCLC 54335090)

1910: Queens’ College, Cambridge, by C. W.

in Country Life, Vol. XXVII, No. 684, 1910 February 12, pp. 239–43. (ISSN 0045-8856)

1922: A little history of S. Botolph’s, Cambridge, by Arthur Worthington Goodman. (OCLC 776794335)

1923: The Life and Reign of Edward the Fourth, by Cora Louise Scofield (1870–1962). (OCLC 266083121)

1924: The Mediæval Hostels of the University of Cambridge, by Henry Paine Stokes; (OCLC 13647604)

1931: Queens’ College Cambridge, by Arthur Stanley Oswald, Part 1, in Country Life, Vol. LXIX, No. 1779, February 21, pp. 222–8; (ISSN 0045-8856)

1931: Part 2, in Vol. LXIX, No. 1780, February 28, pp. 262–8;

1931: Part 3, in Vol. LXIX, No. 1781, March 7, pp. 290–6.

1936: A history of St. Catharine’s College, once Catharine Hall, Cambridge, by William Henry Samuel Jones. (OCLC 5023706) [Chapter 1 relevant to the site of the first foundation of St Bernard’s College]

1951: A Pictorial History of the Queen’s College of Saint Margaret and Saint Bernard, commonly called Queens’ College Cambridge, 1448–1948, by Archibald Douglas Browne (1889–1977) & Charles Theodore Seltman. (OCLC 7790464)

1966: Cambridge University Press 1696–1712: A Bibliographical Study, by Donald Francis McKenzie. (OCLC 11174583) [Chapter 2 relevant to the site of the first foundation of St Bernard’s College, subject to corrections in 1991]

1985: The Household of Queen Margaret of Anjou 1452–3, by Alexander Reginald Myers (1912–1980), in Crown, Household, and Parliament in Fifteenth Century England, pp. 135–209. (ISBN 978-0-907628-63-7)

1987: A History of Queens’ College, Cambridge, 1448–1986, by John Twigg. (ISBN 978-0-85115-488-6)

1991: A Cambridge Playhouse of 1638?: Reconsiderations, by Alan H. Nelson; and Iain Richard Wright [Fellow], in Renaissance Drama, New Series vol. 22, pp. 175–89. (ISSN 0486-3739 eISSN 2164-3415) [response to the 1966 book and 1970 article A Cambridge Playhouse of 1638?]

2022: Queens’ College, Cambridge, by John Goodall, photos by Will Pryce, in Country Life, Vol. CCXVIII, 2022: Part 1 in No. 5, February 2, pp. 62–67; Part 2 in No. 6, February 9, pp. 46–51. (ISSN 0045-8856)

2022: The First 40 Presidents of Queens’ College Cambridge : Their Lives and Times, by Jonathan Hudson Dowson [Fellow Commoner]. (ISBN 978-1-83975-889-8)