Queens’ College lost most, or maybe all, of its silverware in 1642, when it was sent to King Charles I in response to his request for a loan to assist the royalist cause in the civil war against the parliamentarians. The records [1856] show that Queens’ loaned to the king: 5914⁄16 ounces of Gilt Plate, 92312⁄16 ounces of White Plate; and the President and Fellows personally loaned £185 in cash. None of these loans was ever repaid.

As a consequence, Queens’ now has little or no silverware that pre-dates 1642, unless it was an older piece donated after 1642.

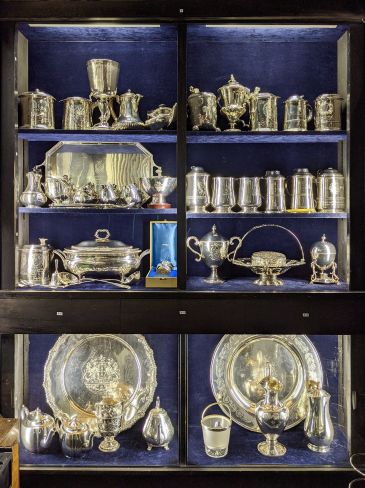

Most of the silverware shown in the lists linked below (apart from normal table cutlery) was acquired by donation from members of the College, particularly from a category of student known as “Fellow-Commoner”: such students paid higher fees than normal (typically double the fees paid by a pensioner) in return for extra privileges, including eating (taking commons) with the Fellows, and distinctive gowns. They were usually the sons of wealthy families. Few of them graduated, and some never even matriculated. There was a custom that Fellow-Commoners left gifts to their College as they departed, and that gift would normally be table silver.

The practice of students being admitted as Fellow-Commoners died out in the 19th century: the final engravings of silver recording gifts from Fellow-Commoners were around 1833, and the final admissions as Fellow-Commoners were in the 1860s (and the Fellow-Commoners admitted after about 1837 tended to be mature students only).

Today, the term “Fellow-Commoner” survives with a different meaning: an honorific title for a person who is not a Fellow, but has been awarded membership of the S.C.R., with associated dining privileges on High Table: such modern Fellow-Commonerships are normally awarded in recognition of ongoing academic or professional support of the College’s mission.

From the 1920s onwards, it became common for the Fellows themselves to donate silver to the college, particularly (a) to mark an event worthy of celebration; or (b) if they were leaving the Fellowship or S.C.R. to move on elsewhere. This practice seems to have died out by the 1990s.

A puzzle, and some speculative solutions.

There are repeated instances of items having hallmark dates many decades later than the date of the donor’s gift, or date of the donor’s time at college, engraved on the item. In some cases, the hallmark date is long after the death of the engraved donor. Some speculative reasons why this might come about are: (1) maybe, gifts for the purchase of silver were held in money form until a suitable need for the purchase of silver arose (unlikely); or (2) maybe, gifts arrived in the form of legacies when the donor died, but the silver purchased from the gift was engraved with the date of the donor’s career at college (one known case); or (3) maybe, when old or damaged silver was disposed of, the donation recorded on the outgoing silver was carried forward and re-engraved on replacement items. The motivation for (3) might have been the other way around: when new silver was desired, but could not be afforded, existing silver was deliberately sacrificed to fund the new acquisitions, but the engraved donor record carried forward.

Of those three possibilities, there is documentary evidence for the third (names carried forward onto exchanged silver), by comparing the Inventory of the contents of the President’s Lodge taken in 1761 with later silver bearing the same name (the earlier pieces no longer existing):

| Donor’s name | Usage in 1761 | Later usage |

|---|---|---|

| Clapham | Cup & cover | 1762 Candlesticks |

| Lloyd | Two tea waiters | 1762 Salver |

| Yarner | Tankard | 1762 Hot water jug |

| Crofts | Snuffer & stand | 1781 Candlesticks |

| Garbrand | Tankard | 1781 Mugs |

| Rolle | Tobacco plates | 1781 Candlesticks |

Lists of silverware

In the pages linked below, silverware is presented in chronological order of its hallmark date: this might be earlier than the date of acquisition, which in many cases is not known exactly. If the date of production is unknown, then the date of acquisition is used instead. A number in square brackets is the 1959 inventory number for that item. Unless otherwise specified, all items are of sterling silver.

References and Further Reading

1856: Inventory of the Plate sent to King Charles I by Queens’ College, Cambridge, and receipt for moneys advanced for his service by the President and Fellows, 1642, by Charles Henry Cooper, in Proc. Cambridge Antiquarian Society, Vol. I (1859):241–52. (ISSN 0309-3603)

1895: Catalogue of the Loan Collection of Plate Exhibited at the Fitzwilliam Museum, May 1895, Pub. Cambridge Antiquarian Society. (OCLC 18957218)

1896: An Illustrated Catalogue of the Loan Collection of Plate Exhibited in the Fitzwilliam Museum May 1895, by John Ebenezer Foster and Thomas Dinham Atkinson. (OCLC 10531363) [expanded and illustrated edition of the 1895 catalogue]

1910: Old Plate of Cambridge Colleges, by Edward Alfred Jones, pp. 59–63 & plates LXVII–LXX. (OCLC 5163157)

1931: Catalogue of an exhibition of silver plate belonging to the University and Colleges of Cambridge, by Edward Alfred Jones, Ellis Hovell Minns. (OCLC 49878337)

1941: MS Catalogue of the Plate of Queens’ College, by Edward Alfred Jones, M.A., F.S.A. [Unpublished, held by Queens’ College bursarial archive]

1951: Silver Plate Belonging to the University the Colleges and the City of Cambridge : catalogue of a Festival of Britain Exhibition held in the Fitzwilliam Museum. (OCLC 54338189)

1959: Queens’ College Cambridge : Inventory and valuation of the Silver, Old Sheffield Plate, and Electro-plate kept in The Buttery and in The President’s Lodge, by Tessiers Ltd. [Unpublished, held by Queens’ College bursarial archive]