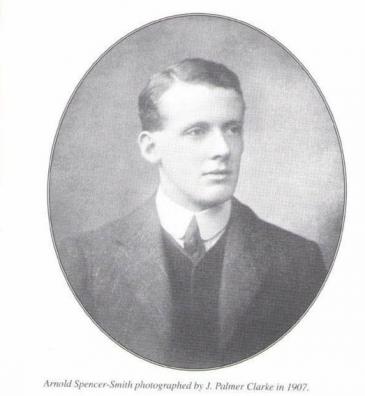

The 9th March marks one hundred years since the death of Queens' alumnus, Rev Arnold Spencer-Smith, who was a member of Ernest Shackleton's ill-fated expedition to cross the Antarctic, to salvage some glory for Great Britain after the Norwegian explorer Amundsen had beaten Scott to the South Pole in 1911. He acted as both Clergyman and photographer.

Spencer-Smith (1883-1916) followed his brother Philip (1901) to Queens' to read History in 1903. After first working as a teacher, he was ordained as a minister in 1910.

A biography of Arnold Patrick Spencer-Smith can be found in the 2000 edition of the Record:

In 1914 Spencer-Smith submitted his application to join the 'British Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition'. Shackleton had proclaimed that "there remains but one great main object of Antarctic journeying - the crossing of the South Polar Continent from sea to sea". He planned to cross with the main party from west to east, from the Weddell Sea, south of South America, across to McMurdo Sound in the Ross Sea. south of Australia. Meanwhile, a second team would land at McMudo Sound and walk 700 km towards the South Pole, establishing depots of food and fuel to help the main Shackleton group heading east to complete their journey. Spencer-Smith was the chaplain and photographer of this second group. Most of this 'B team' sailed from England on the liner Ionic, calling at Cape Town before proceeding to Sydney where their ship the Aurora was being refitted for the expedition at Cockatoo Dock. The Aurora sailed to Hobart to pick up the dogs and then set out for the Antarctic on Christmas Eve 1914.

The story of the disasters that befell the main Shackleton group is well-known. Their ship, the Endurance, became trapped in ice in the South Atlantic and drifted for nine months before sinking in October 1915. The 28 men on board floated in whalers on the pack ice for a further five months before landing on Elephant Island, a storm-swept spot near the Antarctic Peninsula. Shackleton and five others set off on an epic row 1200 km to South Georgia to fetch help, returning to rescue the others in August 1916.

Meanwhile, the 'B team', knowing nothing of the desperate plight of the main expedition, set off to set up Shackleton's food depots. First of all the Aurora could not get within 14 km of Captain Scott's Discovery Hut, their intended base, and had great difficulty anchoring near Cape Evans. Undaunted, the team set off in three groups with sledges and dogs. Conditions were atrocious and most of the dogs died. On 23 March 1915 Spencer-Smith was among a party of four picked up by the Aurora from the Discovery Hut and delivered to Scott's hut at Cape Evans. It would become their winter base and haven. At some point during the stay, Spencer-Smith lost his wallet containing photographs of camping expeditions in the hill near Merchiston down the side of the bunk where it was to remain undiscovered for 84 years.

On 6 May, when the Aurora's skipper was ashore leading one of the sledging parties, the ship snapped her hawsers and disappeared, her crew still aboard. She drifted for 10 months, right out of the Ross Sea into the Southern Ocean. The crew managed to sail her to New Zealand but the 'B team' was stranded. They decided to go ahead with their mission, unaware that Shackleton and his party were by then adrift on the ice-locked Endurance, their expedition abandoned.

Harrowing diaries detail what the 'B team' experienced - atrocious weather, inadequate food and clothing, frostbite, hunger, scurvy, and snow blindness. On 19 January 1916 Spencer-Smith was near the base of Mount Hope and was so ill with scurvy that the party had to leave him in his tent with what food they could afford. Ten days later and after perpetual blizzards they returned. He was still alive. For 40 days they sledged him back towards Cape Evans, but on 9 March he died, his body blackened by disease. He was buried in his sleeping bag, a bamboo cross on a cairn at the graveside. One of his team reported, "He never uttered a word of complaint." Two other members of the 'B team' perished. It was July 1916 before the exhausted survivors reached Cape Evans and January 1917 before they were rescued by Shackleton in the repaired Aurora.

In his final diary entry on 7 March 1916, Spencer-Smith dedicated the entry to his father, mother, brothers and sisters. He was 32 years old. Spencer-Smith was posthumously awarded the Polar Medal in silver.

This is not Queens' only connection with Shackleton's expedition. Professor Michael Shackleton (1971) was Shackleton's great-grandnephew and one of the other crew members, Ernest Wild, was a member of the 'B team' and took great strides in trying to keep Spencer-Smith alive. Ernest Wild had two great-great-nephews who studied at Queens' and recently "completed unfinished family business" in retracing Ernest Wild's steps on an expedition to the South Pole with other descendants of Sir Ernest Shackleton's 1907-1909 Nimrod Expedition.

You can find out more about the Shackleton expedition and Arnold Spencer-Smith at the Polar Museum which has currently mounted an exhibition, By Endurance We Conquer: Shackleton and his Men, which will run until 18 June 2016. It will be followed by a display on the Ross Sea party and will commemorate the centenary of Shackleton's arrival at Cape Evans to rescue the survivors in January 1917.