Article produced by The Revd Dr Jonathan Holmes, Keeper of the Records.

More photos can be found here: https://flic.kr/s/aHsmuPq3i7

Queens’ College First World War Roll of Honour

Please click on the link above to see the First World War Roll of Honour.

Students in Residence in the First World War

The majority of undergraduates joined the Army in the recruiting boom of the autumn of 1914 and early 1915. Many of those students who matriculated in the Michaelmas Term of 1914 joined up within days or weeks. The Dial for the Michaelmas Term 1914 lists 142 Queens’ men already known to be serving in the Forces. Other young men with places at Cambridge did not come up for the start of term as they had already enlisted soon after Britain’s declaration of war on 4th August. By early 1915 there were few students in residence. For the University as a whole, there were 3,181 undergraduates in the Easter Term 1914, but only 491 in the Easter Term 1917. Those left were of three groups: recent school leavers who were too young to enlist, foreign students and those of lower medical grades who were unable to join up – ‘Infants, Internationals and Invalids’ according to soldiers training in Cambridge.Matriculations at Queens’:

1912 57

1912 57

1913 52

1914 35*

1915 21

1916 7**

1917 4

1918 22

1919 179***

*The Vice-President wrote this in the Matriculation Book “The above entries, thirty-five in number (all that are left of sixty), were made by me this 28th day of October 1914. Bella, horrida bella”. This is a quote from Virgil, Aeneid 6.86-7: ‘Bella, horrida bella,/et Thybrim multo spumantem sanguine cerno’ (I see wars, horrendous wars, and Tiber foaming with much blood).

** Compulsory conscription was introduced in 1916

*** This figure includes 14 Naval Officers (studying Engineering as part of their training) and 11 “American University Students” (presumably officers awaiting ships to repatriate them to the U.S.A.)

Poems by Kathleen Wallace, née Coates

Basil Montgomery Coates was born on 10th September 1893, the son of William Coates (1857-1912), Lecturer in Mathematics at Queens’ and Senior Bursar. He was educated at the King’s Choir School and the Perse School in Cambridge, then at Oundle School. He came up to Queens’ in 1912 to study for a career in medicine. However, he was a member of the Officers’ Training Corps and so volunteered for the Army in 1914. He went to France in the early summer of 1915, serving at the front in the Ypres Salient as a Second Lieutenant in the 10th Battalion of the Rifle Brigade (The Prince Consort’s Own). He soon established a reputation for going out on patrol – according to his commanding officer he was “our best scout and absolutely fearless and had already obtained valuable information”. On 7th September 1915 he went forward to scout enemy lines and was killed within about 80 yards of the German trenches. There is no known grave. In letters to his mother or to Oundle, fellow officers described Basil Coates as “always cheerful and considerate”, “so good natured and (with) such a charming manner”, “one of the bravest men I have known”, “everyone was very fond of him”. He is commemorated on the Ploegsteert Memorial in Belgium and also at Queens’, in St Mark’s, Newnham, at the Cambridge Guildhall, at the Perse, and at Oundle.

Basil Coates’s older sister Kathleen was educated at the Perse High School for Girls and then, from 1909, read Modern Languages at Girton College. She had to take a year out because of illness, thus eventually coinciding with her brother as an undergraduate. She specialised in French, taking the MML Tripos Part I in 1912 and Part II in 1914. In 1918 she published a collection of poems entitled Lost City Verses, many of them expressing her grief and sense of loss on remembrance of her brother. In 1917 she had married a Canadian soldier, Major James Hill Wallace, attached to the Canadian Mounted Rifles. After the War they spent some time in his native Ontario before going to China for several years. The family (she and Major Wallace had four sons) returned to England in 1927. Her China experiences were the inspiration for a series of novels set in China, published between 1930 and 1938, of which the most successful was Ancestral Tablet, 1938. There were also novels set in Cambridge, including Grace on their Doorstep, And after that the Dark, and Time changes the Tune, the last published in 1948. In all she wrote over 20 novels including two quite notable fictionalised biographies, Immortal Wheat (about the Brontës) and This is Your Home (about Mary Kingsley). In later life she became quite a successful writer of children’s stories. Her obituary in The Times said of the novels that they were “pleasant and easy to read”. Kathleen died in 1958 (The Times put her age at 76, but she was in fact only 68). Some of the poems she published in 1918 show the rawness of her loss and give the reader a sense of what it was like for those ‘on the home front’ as news of the casualties came in.

Interval: Front Row Stalls

Over the footlights the ankles caper,

The grease paint glistens, the fringed eyes glance;

The last note shrills, and the curtain runs.

The man beside me opens a paper:

“Bitter weather – three mile advance –

Heavy losses – we take the guns.”

And between my eyes and the crimson lights

Move the ranks of men who sat here o’nights,

And now lie heaped in the mud together,

Stiff and still in the bitter weather.

Walnut Tree Court

The court below drowns in an emerald deep

Of dusk, all murmurous

With things the river whispers in its sleep;

I, leaning outward thus

From this high window, over the silence, hear

Your voice, your laugh, and know

Down in the dusk, and infinitely near

You stand below….

Died of Wounds

Because you are dead, so many words they say,

If you could hear them, how they crowd, they crowd;

“Dying for England – but you must be proud” –

And “Greater love, honour, a debt to pay”,

And “Cry, dear”, someone says; and someone, “Pray!”

What do they mean, their words that throng so loud?

This, dearest; that for us there will not be

Laughter and joy of living dwindling cold,

Ashes of words that dropped in flame, first told;

Stale tenderness, made foolish suddenly.

This only, heart’s desire, for you and me,

We who lived love, will not see love grow old.

We who had morning time and crest o’the wave

Will have no twilight chill after the gleam,

Nor for any ebb-tide with a sluggish stream;

No, nor clutch wisdom as a thing to save.

We keep for ever (and yet they call me brave)

Untouched, unbroken, unrebuilt, our dream.

Yesterday

The winds are out tonight,

Strange winds, blown from a far-off troublous sea,

Rending the sky over the chimney pots,

Into a writhing web of jade and pearl –

And lashing my sedate black London trees

All into wonder and a breathless maze.

I wonder if you hear?

From your still bed under Flanders soil,

I wonder if you know the winds are out?

For, if you do, I know across your sleep

There comes the dream that’s tugging at my heart

Alone here with the lamplight and the fire,

And the day dying over London roofs:

The thin white road

Leaping between the fenlands, where the sky

Swoops down to meet the fields, the flat brown fields,

With never a hill’s curve, only poplar boughs

Like spires out of the mist at the day’s edge.

And all the mad winds of the world full cry

Careering through the dusk into the town.

And down the narrow streets,

Under the grey towers and serene grey walls,

Under the yellowing elms along the Backs,

The winds went rollicking and dancing still;

Swaying the chain of lights down King’s Parade

And driving purple cloud-wrack down the sky

Running red flame behind the spires of King’s.

And so they came to us

Beating with wild wings in the court below,

Rocking the room, breaking the fire in gusts,

Filled with the spice of dead leaves and wet boughs,

Just as they come to me, alone, tonight.

That knew no shadow of purpose, but were glad,

When the glad winds raced under Cambridge walls.

Unreturning

Under these walls and towers

By these green water-ways,

Oh the good days were ours,

The unforgotten days!

Too happy to be wise

When the road used to run

Under such maddening skies

Headlong to Huntingdon.

Paths where the lilac spills

Blossom too rich to bear;

Gold sheets of daffodils

Lighting the Market Square;

Shimmer of gliding prows

Where the shade is cool,

Tea under orchard boughs,

Smoke-rings by Byron’s Pool.

Sunset at back of King’s

Behind the silver spire,

Talk of uncounted things

Over a college fire –

Red leaves above your door,

Grey walls and echoing street

Whose stones will never more

Ring to your passing feet;

Strange! To think that Term is here,

Life leads the same old dance,

While you lie dead, my dear,

Somewhere in France …

A School for ‘Temporary Gentlemen’: ‘A’ Company, No.2 Officer Cadets at Queens’

Early in 1916 Cambridge became (until 1919) the leading venue for training junior army officers in the country.

Early in 1916 Cambridge became (until 1919) the leading venue for training junior army officers in the country.

Queens’ and Pembroke were at the very centre of this vital part of the war effort.

Following the declaration of war, the Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge University had been empowered to place all grounds and buildings of the colleges at the disposal of the War Office. For example, 1st Eastern General Hospital was built from huts on the cricket grounds of King’s and Clare College off Queen’s Road (where the University Library now stands) and would care for many of the wounded sent home from the Western Front.

Kitchener’s massive expansion of the Army in late 1914 required large numbers of officers to lead the new units. Thousands of university and public school men – many of whom had prior service in a school or university Officer Training Corps (OTC) – were granted immediate commissions. These ‘temporary officers’ were expected to fill in any gaps in their military knowledge by learning on the job. By December 1914, it had been recognised that thousands of potential officers were serving in the ranks, ‘so it was decided that NCOs and other ranks who were recommended by their commanding officers would be given a short course of officer training for four weeks’. This training was to be carried out by Territorial units such as the various university OTCs (which by then had few undergraduates to train), and, if suitable, the candidates were commissioned. Cambridge University OTC (CUOTC) was one such unit, and it set up the ‘Cambridge University School of Instruction’ at Pembroke. 11 courses were held at the School of Instruction between December 1914 and February 1916 and ‘a total of 3,744 officers passed through the school.

However, by the autumn of 1915 it was apparent that this ad hoc way of training officers – where they still had to learn many of the basics ‘on the job’ – was hopelessly inadequate. The rapid expansion of the Army combined with steady casualties meant that men with military experience were thinly spread. This was particularly true of units in Kitchener’s New Armies and the Territorials. So, in February 1916, a more comprehensive training scheme for officers was set up with the formation of the Officer Cadet Battalions (OCBs) which provided a four-month course. A total of 24 OCBs were formed, the first twelve by June 1916 with at least six more by December 1916 and the remainder by July 1917. Cambridge was home to three OCBs: No. 2 based at Pembroke, No. 5 based at Trinity and the Garrison OCB (later No. 22) which was based at Jesus. The latter was formed to train officers for the home defence units which were guarding the East coast against the threat of German invasion and raiding activity and consisted of men of lower medical grades who were not fit for service overseas.

A candidate for a commission had to be recommended by his commanding officer. Once he had been accepted he would be posted a few weeks later to one of the OCBs. Pembroke was the obvious choice to be headquarters of No. 2 OCB. Given that the staff of CUOTC were running the skeleton of CUOTC as well as the School of Instruction from the Old Library, it was merely a matter of expanding the School of Instruction and converting it into an OCB. Lt-Col HJ Edwards, the 46 year-old Commanding Officer of CUOTC and Senior Tutor at Peterhouse was thus appointed as CO of No. 2 OCB. The battalion consisted of five (later six) companies, each of 4 platoons of about 30 men. The companies were billeted in Queens’ (‘A’ Company), Pembroke (‘B’ Company), Emmanuel (‘C’ Company), Corpus Christi (‘D’ Company), Peterhouse and Downing (‘E’ Company). ‘F’ Company was established a few months later and was based at Christ’s until September 1917 when it moved to Ridley Hall. The total strength of the battalion across all the colleges averaged around 800 men, although a peak strength of over 1,200 was attained in May 1917.

Officer cadets in Cambridge were not members of the University or of the colleges in which they were billeted. They did not matriculate nor receive any formal academic qualification. The War Office was effectively renting the colleges – not unlike a conference would today – but for the duration of the war. Academic staff of the University lamented the silence which had befallen their colleges before the arrival of the cadets. HF Stewart, The Dean of St Johns wrote in a cadet journal: “A Cambridge college does not exist entirely for the sake of its undergraduates …” but “without its junior members it hardly lives a life worth having. … the college needs young blood in order that it may truly live.” With the arrival of the cadets “our pulse began to beat again. Young men were moving among us once more; the Hall was filled thrice a day; some lecture rooms resumed their uses for instruction and smoking concerts.” It is likely that the President and Fellows of Queens’ had similar sentiments. Probably for this reason, the cadets were not discouraged from thinking of themselves as quasi members of the colleges in which they were billeted. The journals of the Cambridge OCBs usually contain a welcome from the respective Master or Dean encouraging them to think of the college as ‘theirs’ and to enjoy the facilities.

Most of the OCBs published magazines or journals and the cadets were actively involved in their editorial and publication. These sources allow us to build a picture of life as an officer cadet. The magazines and journals produced by OCBs are close cousins of the ‘trench newspapers’ produced on the fighting fronts. An OCB’s magazine would typically be published at the end of the course as a souvenir and would often contain details of cadets’ regiments and addresses so that they could keep in touch. Every company in No. 2 OCB produced its own journal for at least one of the courses.

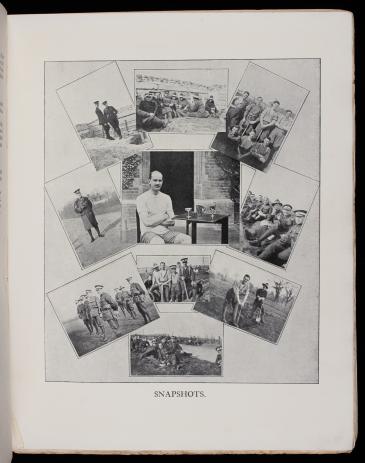

One ‘A’ Company at Queens’ in 1918 produced a particularly detailed magazine, “The Annals of A”. The factual articles included a brief history of the College as well as reports on several sports teams. There is an account of a Maori cadet saving two soldiers from drowning in the Cam, accounts of ‘raids’ on other companies and a number of light-hearted contributions. There is even a poem about Queens’ and an article about punting. There were 120 men on the course, Including New Zealanders, Australians and Canadians, as well as home-grown Brits. This particular group was especially notable as it included a group of Maoris – the first native New Zealanders ever to be commissioned in the Army. This was at a time when the Manual of Military Law forbade men not of ‘pure European descent’ from becoming combat officers. A decision appears to have been taken that officer cadets from the Dominions would only be sent to the OCBs in Oxford and Cambridge. It is not known on what grounds this was made, but one contemporary account describes it as “a happy decision” and that the Dominion cadets had the “opportunity of drinking in the fine traditions” and felt “most deeply” the “haunting charm of these old seats of English learning and civilization.”

The magazine appears to have been funded through advertising, with many local businesses and even London-based outfitters placing copy. A unique feature of the magazine is an advert placed by the High Commissioner of New Zealand touting for colonists and visitors and a similar one from New South Wales. There are photographs of the cadets at work under instruction and at leisure and a whole series of sports team photographs – ‘Rugger’, ‘Soccer’, ‘The Runners’, ‘The Boxers’ and comments on Tennis and Rowing, even a Choir. Finally there is a list of the participants, each with a note of their Regiment, a little personal comment and a home address so the participants could keep in touch. The majority of the cadets were veterans with a few months or even years of active service. Many had been awarded gallantry decorations whilst in the ranks. A minority were public or grammar school boys who had just left school.

Many of the instructors were veterans of the Western Front recovering from serious wounds. Others were ex-scholars with military backgrounds, for instance in public school OTCs, Reserve Officers too old to fight. The company structure was completed by a number of senior NCOs who were usually regular soldiers. On arrival at an OCB the new cadets took off all badges of rank. They were given a white band to put around their caps, and a numeral – a brass ‘2’ – to replace their cap badge. This rendered all cadets equal, regardless of whether they had been fresh-faced schoolboys or battle-hardened senior NCOs. The cadets were billeted two or three to room, a far cry from the dozens that would have shared a barrack room in basic training. The OCBs ‘endeavoured to generate something of the peacetime atmosphere of university life.’ Whilst military training formed the core, several afternoons a week were typically devoted to sport, and the cadets had sufficient spare time to take part in theatre and musical activities. The syllabus for the OCB course in 1916 included training in map-reading, musketry, anti-gas measures, reconnaissance, open warfare, bombing, field engineering (including the siting and laying out of trenches and the construction of tunnels and dug-outs), ‘interior economy’ (which covered a variety of logistical and administrative topics) and military law. Reveille was at 6 am, and was followed by Physical Training in Coe Fen from 7 till 8. This might be followed by lectures, drill, musketry on firing ranges or field exercises. In order to support delivery of lectures, No. 2 OCB constructed a short length of trench in the grounds of The Leys School in Cambridge. Field exercises became increasingly important in the third and fourth months of the course. There was a training area on the Gog Magog hills with an extensive trench system. The cadets marched there for instruction and practice in digging trenches, as well as lectures and practice in both attack and defence. Over the years the training evolved to include, for instance, working alongside tanks following the first use of this new weapon on the Somme on 15 September 1916. Dummy tanks – consisting of a canvas frame mounted on bicycle wheels, with broom handles for guns – were used in the Gog Magog training area. Many valuable lessons were learned during the bloody Somme campaign of 1916 and the infantry tactics which evolved were distilled into a pamphlet SS 143 Instructions for the Training of Platoons for Offensive Action which was published in February 1917. This document recognised the devolution of decision making to the most junior officers who, in 1917, were expected to demonstrate levels of initiative and autonomy that had not been expected of men commissioned before the Somme. The OCBs were instrumental in instilling this initiative into their charges.

Cadets were continuously assessed during the course. Field exercises and drilling squads of fellow cadets were used to assess their capability in command roles. Cadets also had to pass three exams which covered all of the subjects such as military law, field engineering and musketry. The exams were set centrally by the War Office each month and would be sat by all cadets passing out of all the OCBs in that particular month. A cadet who failed to be recommended for a commission was returned to his unit with the rank he had held when he left it.

Thousands of officer cadets were training with the OCBs at the time of the Armistice in November 1918. Most would have wanted to be demobilised as soon as possible, many being either long serving or in critical occupations. The War Office gave all officer cadets who had enlisted for the duration a choice at the end of December 1918. One option was to return to their units ‘in order to continue to serve in their present ranks’. However, this meant that demobilisation would be at an uncertain date in the future. The alternative was to continue their training with ‘a view to being recommended for a commission’, and then being commissioned and immediately demobilised and discharged to the reserves without ever serving as an officer. It appears that most cadets took this option. No. 2 OCB was wound down in mid-January 1919. Cadets who had not completed their courses were sent to another OCB for their final exams and assessment.

Robert Graves considered that the OCBs “saved the Army in France from becoming a mere rabble”. He wrote that “few of the new officers were now gentlemen” but that “their deficiency in manners was amply compensated for by their greater efficiency in action”. By ensuring a consistently good minimum standard of junior leadership, the OCBs played a vital part in the professionalisation of the British Army, and thence the final victory in 1918. Not only did the OCBs ensure adequate quality, they also provided quantity. Despite the horrendous casualties among junior officers, they were present in greater numbers in the typical British infantry battalion in 1918 than they had been in 1914.

Much of the text abridged from an article published in the 2018 edition of The Pembroke Gazette 11

© Charles Fair 2018

The Armistice Signed – the Dial

Editorial – The Dial – Issue No. 32: Michaelmas Term 1918

The “Curfew” bell rings out its nightly peal again – and thereby hangs a tale. It tolls the knell of many other things of the past beside the restriction which has checked its voice for four years. But the parable needs no interpretation. The fact is too stupendous. Never has The Dial appeared in such a momentous era.

In sooth we are seeing history in the making… But the history of the war is not written yet, even on the stern face of time, and in the unlettered book of the ages. Nay, further we are more than ever now in the melting pot. There was but now one clear aim of all efforts – to crush the monstrous Eagle; a veritable Hydra lurks beneath the oft-repeated word “reconstruction”.

Yet without forgetting what lies before us, we can rejoice at what lies behind, to remain there for ever. And now our hopes are high as the gloomy days recede, and we look forward to the return of those pre-war conditions here which were wholesome. We are set to work again, chastened… Already our numbers are augmenting and every new term will bring fresh increase. Our real college life will begin anew in its fullness and the broken strands of tradition will be gathered up and, interwoven with the fresh and better experience, will form the old fabric, yet new; a thing purged but not to destruction.

And so once more we emerge, still a thin phantom of our former self, from the scant recesses of a depleted storehouse; but so, we hope, for the last time...

There will be one more and final War List: a plain record of golden deeds unsung: let it be…the key that unlocks the mystery that, whereas we were slaying and being slain, now, though through slaughter and sacrifice, Peace has been brought within sight.

Editorial – The Dial – Issue No. 33: Easter Term 1919

‘Rest after toil’, said a Cambridge poet, ‘doth greatly please’. Maybe he thus expressed his feelings as he reclined on the Backs or in whatever in Elizabethan days offered the attraction of a punt, endeavouring to realise that the Tripos fiend had done its worst... And there is no rest like that which follows after this, like ‘port after stormie seas’.

It befel, as I rested thus… visions of the past ‘came stepping to rear through my mind’. Methought I saw this Ancient University - five years ago is ancient history – in the full vigour of its teeming life. There were men, men, men. Some were votaries of the muse, fat volumes reposed under their arms, as they pursued their way through this seminary of sound learning, unobtrusive meek. To others the field or the river was an only joy, they played and became strong and merry withal... Others again divided their favours … these were they whom they called ‘all-round’ men. There was a cult of Mars, dubbed O.T.C. [Officers Training Corps - ed], but he didn’t matter much. Till one day, all was changed. Vainly I looked for books or bats. The scene is all animation, of men about their business in deadly earnest. I thought when I awoke of August 1914.

Then came the changes thick and fast. Alma Mater began her sorrows as son after son was lost – some for a while, too many never to return. Many were her foster sons. Thousands of troops found themselves in her precincts: officers filled her colleges. Another picture: the officers have gone and a cadet school flourishes in their place. The white-banded cap is ubiquitous, the absence of the gown is equally conspicuous.

But these poor visions receded in their turn and gave place to happier ones. I heard many bells ringing and many shouting crowds surging through beflagged streets. The beginning of the end … was thus joyfully received. From that scene onwards each one was brighter and filled with more figures. Still they came from near and far till scarce room remained for the mass of sons returning. Khaki has been doffed and all things abnormal have been dwindling away… before the attacks of keen spirits eager to return to the good days of yore.

The lean days are over and the future is full of promise. Our guests no longer learn the art of killing but pursue with us, Naval Officers and Americans alike, the paths of sport and learning, and they are most welcome. Once more the cult of Father Camus [i.e. rowing on the Cam – ed] claims scores of ardent devotees and after this long lapse a May Week program [sic] is again before us, with its races and concerts and indifferent weather. … ‘The spirit of the place’ is rekindling its flame and next term the fever of these exciting and uncertain times will no longer be an excuse for any lack of esprit de corps: the College life, we can safely predict, will return to its former proportions.

“Peace after War does greatly please”.

The Dons during the First World War

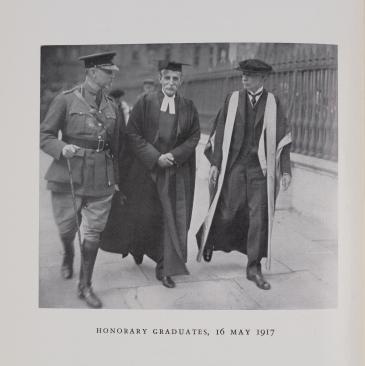

The President – The Revd Thomas Fitzpatrick

Physicist and Alpinist

Thomas Cecil Fitzpatrick was an entrance scholar at Christ’s in 1881 and took firsts in Part I and Part II of the Natural Sciences Tripos. He was elected a Fellow of Christ’s and was ordained as Chaplain in 1888, later becoming Dean. For many years he served as one of Sir J J Thompson’s demonstrators in the Cavendish Laboratory. He was elected President of Queens in 1906, serving until his death in 1931 at the age of 70. Both before and after coming to Queens’ he was a prominent figure in University business, serving as a member of the Council of the Senate, on several occasional syndicates, on the Financial Board, the General Board and on the Schools examination Board. He was a great supporter and a constant friend of the Workers’ Educational Association. He was Vice-Chancellor for the difficult war years of 1915-17. He was again Vice-Chancellor 1928-30. He was asloo Vice-President of the Church Missionary Society. The Revd G.A Chase, an undergraduate at Queens’ when he first arrived and later Master of Selwyn described him thus, “Sparing in speech as in frame, quick and incisive in judgement, impatient of anything that seemed to him slip-shod or ungenerous, always eager to draw others, and especially younger men, into the ambit of University business, but never hesitating to speak out when he differed from them, he always gave and inspired in others a whole-hearted and untiring devotion in the service of the University. Above all and in it all he had the true simplicity of a humble-minded servant of God.”

He was responsible for and contributed himself generously to the restoration of the College in 1910-11. Victorian ‘battlements’ were removed from Old Court and the President’s Lodge renovated, exposing the timbers to give the famous half-timbered building its modern appearance. In 1912 he married Annie Rosa Cook, herself a generous benefactor to the College.

A man of simple tastes and habits, his one luxury was mountaineering, a hobby far from fashionable in the late nineteenth century. He particularly enjoyed climbing in the Swiss Alps. He was “a good mountaineer, especially on rocks, very quick and very active, and an inexperienced man found it difficult at times to follow in the footsteps of his guide or to share his enthusiasm for a long expedition every day, sometimes without much regard for the weather…” He enjoyed summer climbing holidays for many years. Later he and his wife travelled to Palestine, Greece, Algeria and even South America, happily camping in the open air if need be – the sort of holidays which were very uncommon in that era. He was noted for his generosity both to friends and colleagues and to his two colleges – he was a major benefactor of Queens’.

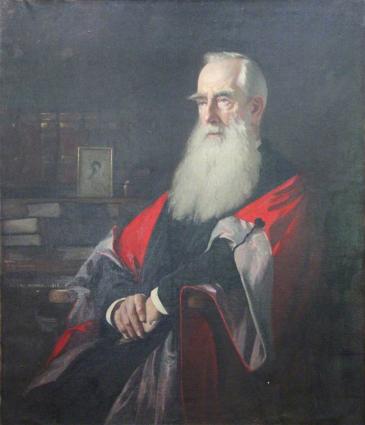

The Vice-President and Tutor – Dr Arthur Wright

Classical Lecturer

“Dr Arthur Wright, the Vice-President and Tutor had been for many years Senior Fellow, and in his curious way virtually the ruler of Queens’. He was a shy and retiring old man, spare of speech and somewhat morose and alarming in his manners, but generous and kind-hearted and entirely devoted to the College. Like many shy people, by his odd mannerisms he unwittingly drew attention to himself. In the chapel services it was his custom to leap up and sit down again before anybody else, and he would be constantly waving his arms about, or combing his venerable beard with his fingers during the service. Conversation with him was always of the briefest nature, and very staccato. In those days, before he took to typewriting, he was much engrossed in the use of fountain and stylographic pens charged with various coloured inks; he had many other fascinating foibles. He was credited with having been the inventor of the complicated stoves which were fitted in all the rooms in the Friars buildings and, lo and behold, when I went to Sandon years later (his brother Benjamin had been Rector there), there was one of these ‘Arties’ fixed in the dining room! Our boats began to do well on the river, and in my second term ‘Arty’ Wright suddenly made up his mind to invite the crew of the Lent boat to a ‘breakfast’. These functions were generally held in the Hall, but Arty decided to have it in his own room; his huge table was cleared and the feast was spread. I was cox of the boat at that time and as such I was pushed into the room first, and I had to sit next to Arty presiding at the head of the table. Of this new venture of his he was obviously very nervous; his meals were always peculiar and often very picturesque and varied, according to the particular diet with which he was experimenting. That morning he sat at the head of the table with a glass of water before him, together with an apple. By way of opening he lifted his glass and declaimed to the table as a whole, “The water at Jerusalem is atrocious!”. Dead silence, while everybody was considering what could be said. Eventually some genius remembered that Arty and Kennett had toured Palestine together, and by skilful manoeuvring, Arty was led on to describe how Kennett and he had bathed in the Dead Sea and had found it impossible to sink. Anyhow, he gave us a very super breakfast!”

In 1914, perhaps with prescience, Dr Wright wrote this in the Matricualtion Book “The above entries, thirty-five in number (all that are left of sixty), were made by me this 28th day of October 1914. Bella, horrida bella”. This is a quote from Virgil, Aeneid 6.86-7: ‘Bella, horrida bella,/et Thybrim multo spumantem sanguine cerno’ (I see wars, horrendous wars, and Tiber foaming with much blood).

The Dean – The Revd C.T. ‘Charlie’ Wood

Divinity and Hebrew Lecturer

Charles Travers Wood was a graduate of Pembroke College. He won a raft of University prizes in Classics, Theology and Hebrew and was appointed a Fellow of Queens’ in 1900 to be Chaplain and Theological and Hebrew Lecturer. In 1907 he became Dean, a post he was to hold until 1940. He continued then as a Fellow of Queens’ and as Rector of St Botolph’s Church until his death in 1961 at the age of 86.

He was a strong supporter of the Scouting movement. After General Robert Baden-Powell’s famous book, “Scouting for Boys” was published in 1907, groups of boys (and girls) all over the country started forming themselves into Scout troops and persuaded adults to become leaders. Leonard Spiller (1909) brought the Scouting fever to Queens’ and that winter seven Queens’ undergraduates started a troop in the Barnwell area of the city. The Boy Scouts Association was officially founded in 1910. Charlie Wood became the first District Scout Leader for the Cambridge Scouts in 1914. In 1910 he had formed the 9th Cambridge ‘Queens’ College Own’ Scout Troop mostly from the boys in the Chapel Choir. At that time each boy recruited for the Choir (from churches around the town) was entitled to a free straw hat each year. Wood diverted the ‘hat money’ into paying for the boys’ train fares to the annual camps. During the First World War, the Choir continued to function (though without many men to provide the Tenor and Bass parts); camps were still held but the boys on them were put to useful ‘war work’, most notably in 1917 picking fruit for Chivers and in 1918 flax, which was used to make the linen for aircraft wings. ‘Spanish Flu’ swept the camp, but all the boys (perhaps because they were out of doors and living in tents) survived. In 1923 Wood became Scout County Commissioner for Cambridgeshire and many scouting events were held at Queens’. He continued to run the 9th Cambridge Scout Troop until it was amalgamated with the 11th in 1960. Charlie Wood was also a very keen cross-country runner, winning a ‘Blue’ in 1897. Several of his trophies are still to be seen in the Old Combination Room. He donated other trophies to the Officer Training Battalions billeted in Queens’ during the War – one of these recently turned up in Australia.

The Bursar – Andrew Munro

Mathematical Lecturer

Andrew Munro was described in his obituary as “a Conservative of the right Cambridge breed” and apparently “used to admit, half in jest but also half in earnest, that he always voted against any change”. He was a Scotsman, born at Invergordon, Ross-shire. From 1886 till 1890 he was a student at Aberdeen University, where he took his M.A. It was not uncommon for promising Scots mathematicians to further their education by taking the Cambridge Mathematical Tripos after their first degree and Andrew Munro duly won a Scholarship in open competition and came up to Queens’ in 1890. He was Fourth Wrangler in the Mathematical Tripos (i.e. the fourth best first) in 1892. He served the College as Bursar, Steward and from 1931 Vice-President. For the first 20 years of his Fellowship he concentrated on his duties as College Lecturer, Director of Studies and Supervisor in Mathematics, working closely with his friend, the Senior Mathematical Lecturer and Senior Bursar, William Montgomery Coates. He made no original contributions to mathematics, seeing it as his primary duty as a College Teaching Officer to teach, but left lecture notes on a wide variety of subjects, all minutely indexed. He had an extensive library of all the latest maths books. His successor as Mathematics Lecturer, E.A.Maxwell, commented, “Pupils will remember his curious faculty, when presented with a problem new to him, of writing down seemingly irrelevant symbols, and suddenly (but almost infallibly) producing the answer”. His nature was essentially kind and sympathetic, but his view of pupils’ abilities was moderated by an instinctive prudence, “which prevented him from fostering undue hopes even in his most promising scholars”.

When Coates died in 1912 Munro ‘inherited’ the post of Senior Bursar (as well as the guardianship of Coates’ children) and steered the College through financially difficult times. It was on his advice that, after the Great War, the College sold most of its farms and invested in Government stocks. The reserves which he built up enabled the College to expand in terms of both student numbers and buildings (the building of Fisher and the adaption of the old Fitzpatrick Hall for the JCR were started before he died). His obituarist in The Dial (A.B.Cook) attributed his successes as Bursar to a combination of financial acumen running in his veins (from his banking forbears), a distinct talent for maths and “an ultra-Scottish attitude of caution and reserve”. He was Senior Proctor twice, once for a two-year period in the midst of the First World War, a particularly difficult and traumatic period for the University.

He regarded it as part of his duties to support undergraduates in all their pursuits and was often to be found at the football field or on the tow path. He remained unmarried, but one undergraduate of the time recalled that “In term time he was a celibate bachelor, but in the vacations he had lady friends in Paris” – perhaps an undergraduate rumour, but maybe the stolid image concealed hidden depths. On his death A.B.Cook wrote, “But if he cared for individuals much, he cared for the College more. Not only our prestige in the Senate House and our triumphs in the Tripos, but our place in the Leagues, our position on the River, our chances at Henley all meant much to him. And realising, as he did, that the College had suffered in the past from lack of wealthy benefactors, he set himself with silent determination, through long years of abstemious self-denial, to make good that defect and was able to bequeath to us and to those who shall come after us the most munificent endowments that Queens’ has ever received”.