Background: the Settlement Movement

In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, public concern began to mount concerning the poverty, deprivation, and squalor of certain parts of Britain’s inner cities. Britain had long been accustomed to sending missionaries overseas: now it seemed that there were needs for social missionaries in parts of Britain itself. The vicar of St Jude’s, Whitechapel, the Rev. Samuel Augustus Barnett, an Oxford alumnus who was only too familiar with the problems evident in his own parish, began visiting Oxford from 1875 onwards, reporting and preaching on the issues, stirring up a great deal of sympathy, interest, and willingness to help. In response to a request for an idea for something better than just a College Mission to the deprived areas, he originated the concept of a University Settlement: a place located in a deprived area, where rich (volunteer students from the university) and poor would live and socialise together, and learn from each other. He presented his ideas to a meeting in St John’s College Oxford in November 1883. The paper was published shortly afterwards. [The Universities and the Poor, by the Rev. Samuel Augustus Barnett, in The Nineteenth Century, Vol. XV, No. 84, 1884 February, pp. 255–61]. A committee was formed, a site purchased, and by Christmas Eve 1884 the first University Settlement, Toynbee Hall, opened in Whitechapel.

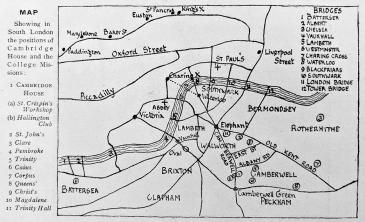

The concept spread rapidly, first at both Oxford and Cambridge, then the major independent schools, and other universities in their own cities, then abroad, particularly in the USA. Oxford University and Colleges created settlements or missions mainly in the East End of London (with a few exceptions), while Cambridge University and Colleges worked mainly south of the Thames, in the deprived areas in and around Bermondsey. Cambridge House had its origins in 1889. By 1910, St John’s, Clare, Trinity, Pembroke, Corpus Christi, and Caius were listed as having Missions in south London, with Queens’, Magdalene, Christ’s and Trinity Hall having clubs or homes there. Unlike Cambridge House, the College Missions were exclusively Anglican, and some did not fully conform to the ideals of a Settlement.

Queens’ College Boys’ Club in Peckham 1901–11

In May 1899, the Rev. J. W. Maunders founded a Boys’ Club. The precise location of this club is not recorded, apart from being on Peckham High Street within the parish of St Chrysostom. After the club ran into financial difficulties, it was adopted by Queens’ College with effect from October 1901, and Maunders was appointed by Queens’ as Missioner.[The Work of Queens’ College in Peckham, by the Rev. J. W. Maunders, pp. 113–20]

On Thursday, October 10th, ‘the Queens’ College Boys’ Club’ was inaugurated at Peckham, the President and several past and present members of the College attending.

[The Cambridge Review, Vol. XXIII, No. 567, 1901 Oct 24, p. 30]

This marked the (somewhat belated) entry of Queens’ into the Cambridge college mission movement supporting South London. We speculate that this timing might be related to the arrival in Queens’ of Charles Travers Wood (1875–1961) as a Fellow in 1900. [He had been an undergraduate at Pembroke College, which already had an active mission in Walworth. Wood became Dean in 1907, and for the whole of his career remained the Fellow most closely associated with the college mission, and with the Boy Scout movement]. At least one fund-raising event for the Mission took place:

A most successful concert was held in the Hall on May 12th, on behalf of the funds for the Queens’ College Mission in South London. Quite 200 were present. A feature of the evening was the excellent violin playing of Mr J.D. Morgan. Mr R. Lascelles’ sleight of hand was also highly appreciated.

[The Cambridge Review, Vol. XXIV, No. 609, 1903 May 21, p. 320]

In 1907, Maunders moved on, and the Rev. R.L. Gardner became Missioner. In 1909/10, a dispute arose within the parish, the full details of which have not come down to us, and Queens’ withdrew from the arrangement in 1911.[The Mission, in The Dial, No. 10, 1911 March, pp. 61–4] Queens’ began to look around for an alternative site for a Mission, which would be free of parish control.

Queens’ House, Rotherhithe, 1911–40

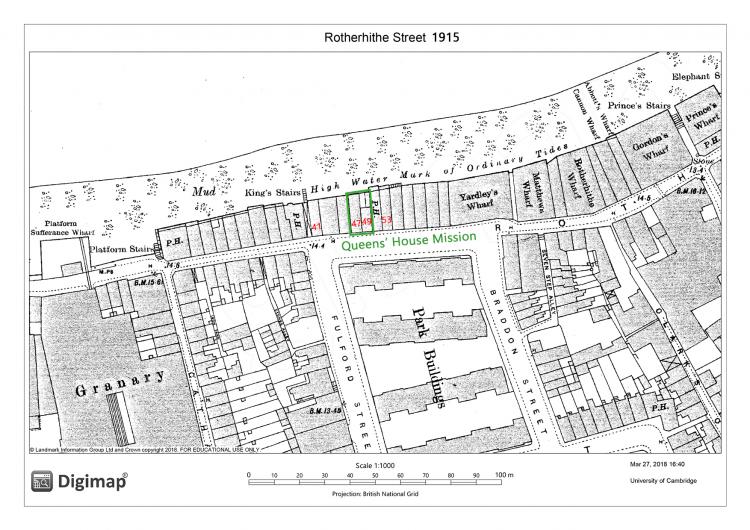

In 1911, a suitable property was found at 47 Rotherhithe Street, which, from October 1898, had formerly served as a Jesus College Mission, called The College House

. After Jesus College had departed, a private individual had maintained some recreational activities there, but now needed to move on. The local vicar thoroughly approved of the scheme to plant a mission in his parish (Christ Church, Rotherhithe). It was at first named The Queens’ College Mission

.

The house contains three good club rooms, a canteen, prayer-room, quarters for two residents and housekeeper, and accommodation for three guests, as well as a spacious balcony overlooking the river.

[The Queens’ College Mission Rotherhithe, by the Rev. J. Kingdon (Missioner), in Cambridge in South London : the work of the College Missions, 1883–1914, 1914, p. 188]

The college also took a lease on the next house in the terrace, No. 49, as a home for the Missioner: the above description seems to take the space of both houses into account. These two houses were part of a run-down 18th century terrace of disparate properties on the bank of the Thames at the Pool of London. The terrace was directly east of King’s Stairs, roughly opposite Wapping Police Station. The rear of the houses rose directly from the bank of the Thames, and had a view to Tower Bridge, about one mile to the west.

The college also took a lease on the next house in the terrace, No. 49, as a home for the Missioner: the above description seems to take the space of both houses into account. These two houses were part of a run-down 18th century terrace of disparate properties on the bank of the Thames at the Pool of London. The terrace was directly east of King’s Stairs, roughly opposite Wapping Police Station. The rear of the houses rose directly from the bank of the Thames, and had a view to Tower Bridge, about one mile to the west.

Map © Landmark Information Group Ltd and Crown copyright 2018.

The work of the Mission consists in running a Boys’ Club, not merely for the sake of providing healthy recreation and amusement, but for furthering their education and developing their religious life. The aim, therefore, is threefold; social, educational, and religious.

[The Queens’ College Mission Rotherhithe, by the Rev. J. Kingdon, 1914, p. 188]

A change of name from The Queens’ College Mission

to Queens’ House

was reported in Queens’ College 1927–1928 [pp. 12–13], and the new name was used for the first time in The Dial No. 58 Lent Term 1928 [p. 4].

The Queens’ House Mission also hosted a Boy Scout troop: the 7th Bermondsey and Rotherhithe:

The annual Whitsun visit of the scouts from Queens’ House, Rotherhithe, passed off very successfully. Rain on the first two days made camping in the Grove an unpleasant business, but these early sorrows were soon forgotton in the glorious sunshine of Whit Monday. On the Monday afternoon a fleet of scandalously overloaded cars carried the entire party to Lingay Fen, where, under the auspices of the Senior Tutor, a programme of bathing, mud-fighting and eating was successfully carried through.

[The Cambridge Review, Vol. LII, No. 1289, 1931 June 5, p. 466]

The work that could be achieved by a College Mission such as this one relied upon two streams of support from students and alumni of the sponsoring college: (i) a steady stream of volunteers willing to stay in the Mission and work with the boys, or to take them to summer camps, and (ii) a steady stream of financial donations. In the end, both would prove problematic.

Throughout the life of the Mission, there were occasional reports in The Dial (termly undergraduate magazine) of mission activities, such as camps, or visits to Queens’ House by undergraduates, or visits to Cambridge by the boys, all of which seemed successful, and evidence of a mission functioning well. But a constant refrain was the parlous state of the finances, and the need for more donations. The Mission was also a regular item in The Record (annual report to alumni), but almost the only thing consistently mentioned each year was the declining financial position.

In February 1934, the Governing Body received a report The Status of Queens’ House, authored by the Fellows most closely involved with the Mission. It is a strange document, leaving the reader with the feeling: if this report was the Answer, what had been the Question? The main discussion of the document is concerned primarily with the importance of keeping the Mission independent of parish control, but the recommendations for the future do not seem to follow directly from that discussion. The Governing Body accepted the three recommendations, which declared the Governing Body to have assumed full responsibility for the Mission, with powers to appoint the Mission committee, and to establish general policy, including appointments of Missioners and relationships with the parish vicar. Quite how these things had been managed before is not recorded.

Apparently, student interest and involvement continued to decline. In February 1939, an open college meeting was called for March 1st, with an agenda paper The Future of Queens’ House Rotherhithe. The overall message was that the Mission was healthy, but support from the students was not: so maybe failure should be recognised, and the Mission closed. The report included the phrase Owing to difficulties in the Parish your committee consider that the present arrangement is one which cannot be continued.

Once again these parish difficulties are not spelled out, but there is an implication that future Missioners might not be able to also be part-time curates in the parish, as had been customary, and so the college would have to pay a full-time, instead of part-time, stipend to any future Missioner. That would have been unaffordable at the subscription levels then current. The meeting was reported as follows:

Queens’ House has had to face a crisis. Mr Bache, whose work in the club has been of inestimable value, was forced to give up. The gap he left was very hard to fill and the idea of abandoning the mission altogether had to be faced.

A letter was sent to every member of the College putting the facts before them and urging them to attend a meeting to be held on March 1st. This meeting was well attended. A proposal to carry on the House for the present with Mr Fricker, an old member of the club, in charge, was carried unopposed. After the sorry financial position and our obligations to old Queens’ men and senior members of the club had been pointed out, the meeting was thrown open for discussion. Many constructive criticisms were made regarding visits to the club, subscriptions and the election of a committee. That the House should be continued was carried unanimously.

All we now need is the whole-hearted support, not of a minority, as in the past, but of a majority; Queens’ House is not just another —— charity, but part of Queens’ from which as much enjoyment can be gained as from any other college club.

[The Dial, No. 91, 1939 Lent, p. 68]

There was a sudden burst of political activity the next term, as recorded in The Dial, centred around a proposed constitution of the Mission Committee. However, not everyone was in support:

there must be a fair number of people who do not approve of such Missions …

[The Dial, No. 92, 1939 Easter, p. 11]

In reaction to events of the previous term, there was a:

… movement to change the committee of Queens’ House from a self-coopting to a democratically elected committee…

[Ibid]

all sports clubs, political and religious societies, with a membership of twenty or over, should nominate three men (one of each year) for a [Mission] committee to be elected terminally by ballot

[Ibid, p. 32]

It is not clear how this proposed democratic arrangement tallied with the Governing Body’s motion of 1934 assuming the right to nominate the committee.

Mass evacuations of children from London at the start of the war removed most of the clients that the Mission was intended to serve. In October 1939 and January 1940, the Governing Body resolved:

Agreed regretfully to close the Queens’ House Mission at Rotherhithe owing to the war and to authorise the Committee to take such steps as are necessary to wind up and terminate the lease of the property.

[Conclusion Book, 1939 October 4]

Agreed to accept financial liability to the extent of about £60 for the winding up of the College Mission at Rotherhithe, the severance of all official College connection with Queens’ House, and the complete termination of the lease on the property, 47 to 49 Rotherhithe Street, London, dated 2nd November 1934 between the President and Fellows of Queens’ College and Mr Henry Pocock.

[Conclusion Book, 1940 January 26] [H. Pocock was the barge-building company operating out of 43–45 Rotherhithe Street]

This was reported to alumni as follows:

Unfortunately it seems impossible to continue the work in Rotherhithe, both because of the shortage of funds and because so many of the boys have left the district that the work is at a standstill.

[Queens’ College 1938–1939, p. 14, probably written early 1940]

Coincidentally, C.T. Wood retired in June 1940, to become a Life Fellow.

Queens’ House after 1940

The name Queens’ House

lived on as a brand under which charitable action continued to be delivered from that property by other organisations. Subsequent users of that name were less particular about the apostrophe, in either its position or existence.

In 1941, the local Bermondsey charity Time and Talents

opened a branch registered at 53 Rotherhithe Street, operating under the Queens House

name.[The evidence for voluntary action, by Beveridge & Wells, 1949, p. 129] Although the authority given here quoted the address as 53 Rotherhithe Street

, it is reasonably clear from the report quoted below that Queens House

itself continued to be at No. 47, but that there was also an annexe along the street

which might refer to No. 53:

Queens House, the college Mission in Rotherhithe, London … was re-opened under a new management in 1941. Before the war the emphasis had been on Scouting, but it is now a mixed Youth club of boys and girls…

The premises are a converted barge-builder’s establishment on the South bank of the Thames, with a fine view of Tower Bridge to the West, and the Wapping river-side and Limehouse to the North. … They have a large clubroom on the ground floor, two games rooms above, a canteen and a quiet room on the 2nd floor, and a chapel at the top. [consistent with the 1914 description above] In the annexe along the street [No. 53?] there is a well-equipped carpenter’s shop, and another fairly large hall, which the warden is thinking of turning into a small theatre.

The College is no longer responsible for the House, but they retain our name and are very anxious to promote the connection with us.

[The Dial, No. 95, Easter 1947, pp. 33–4]

The club was closed for a period in 1949/50 because of staff shortages. The relationship with college continued still:

Queens’ House maintained a close contact with Queens’ College Cambridge which provided end-of-term visits from parties of undergraduates who spent weekends in Rotherhithe doing odd jobs and sharing all the club activities. Even before the Clubs had re-started in 1950, the Queens’ College Group had been along to help with Christmas parties, as well as painting and decorating, and they entertained most royally a party of Junior Boys for a memorable day in Cambridge. Arthur Myers [Queens’ 1946–48] was the Cambridge correspondent during the depressed year of closure in 1949, and suggested acting as Caretaker at Queens’ House where he lived for some months with great enjoyment...

[By Peaceful Means, by Marjorie Daunt, 1989, p. 41]

In July 1951, Time and Talents formed a partnership with the Save the Children Fund for the purpose of running and financing Queens’ House and, in October, Countess Mountbatten [president of Save the Children at the time] opened it officially as a Children’s House. Coming down the River in a barge, she arrived at Queens’ House, making a sensational entrance by jumping in through the wide opening formerly used for receiving sacks of flour.

[Ibid]

Back at college this was reported:

The mission … is now run as a youth club by the Save the Children Fund, having been re-opened by the Countess Mountbatten of Burma a few weeks ago.

[The Dial, No. 104, February 1952, p. 35]

In that era, Save the Children operated a network of junior clubs for urban schoolchildren in Great Britain

. [The evidence for voluntary action, by Beveridge & Wells, 1949, p. 281]

The work was well established and, with the assurance of the Save the Children Fund that it would continue, the Executive Committee of Time and Talents reluctantly decided to withdraw its financial support as from October 1953.

[By Peaceful Means, by Marjorie Daunt, 1989, p. 41]

In the 1960 edition of the Bermondsey Official Guide, p. 92, a branch of the Save the Children Fund

is shown operating at Queen’s House Club

, 47 Rotherhithe Street.

In 1964 the London County Council announced its intention to purchase the entire terrace of houses along the riverfront in Rotherhithe Street in order to demolish them and make the area into a public riverside garden. The announcement was reported in the Illustrated London News, accompanied by a drawing of the terrace, with Queens’ House Junior Club

in the foreground. At roof level, the beginning of the spacious balcony overlooking the river

can just be discerned. [Where the L.C.C. Plan to Build a Garden: An 18th Century Thameside Terrace in the Pool of London, in Illustrated London News, No. 6502, 1964 March 14, p. 395]

The buildings were photographed in 1964 shortly before demolition. This view shows the whole terrace 47–59 Rotherhithe Street, after the removal of 43–45. Queens’ House Mission had used 47–49 from 1911 until 1940. Time and Talents had used 47 and 53 from 1941. The Save the Children Fund used 47 as a Junior Club from 1951.

The buildings were photographed in 1964 shortly before demolition. This view shows the whole terrace 47–59 Rotherhithe Street, after the removal of 43–45. Queens’ House Mission had used 47–49 from 1911 until 1940. Time and Talents had used 47 and 53 from 1941. The Save the Children Fund used 47 as a Junior Club from 1951.

Photo Copyright © London Metropolitan Archives, by permission.

The interior ground floor of 47 Rotherhithe Street in 1964. This had been the main club room. The rear windows shown were directly above the bank of the Thames.

The interior ground floor of 47 Rotherhithe Street in 1964. This had been the main club room. The rear windows shown were directly above the bank of the Thames.

Photo Copyright © London Metropolitan Archives, by permission.

The terrace disappeared from Ordnance Survey maps by 1968, except for house No. 41, immediately adjacent to King’s Stairs, which survives to this day in complete isolation as No. 1 Fulford Street.[Know your London][londonphile] This section of Rotherhithe Street no longer exists.[Lost Rotherhithe Street] For a short distance, the Thames Path follows the line of the former street as it passes the former No. 41. The whole area has become part of the King’s Stairs Gardens.

Trivia

The whole terrace 41–59 Rotherhithe Street (including the

The whole terrace 41–59 Rotherhithe Street (including the Queens House Junior Club

) appears as a location in the 1958 movie Behemoth the Sea Monster

a.k.a. The Giant Behemoth

. The monster marches down Rotherhithe Street, flattening cars underfoot, and killing onlookers by irradiation.

Further reading

1884: The Universities and the Poor, by the Rev. Samuel Augustus Barnett, in The Nineteenth Century, Vol. XV, No. 84, 1884 February, pp. 255–61. (ISSN 2043-5290)

1898: University and Social Settlements, ed. Will Reason. (OCLC 3724500)

1903: The beginning of Toynbee Hall : a reminiscence, by Henrietta Octavia Weston Barnett, in The Nineteenth Century, Vol. LIII, no. 312, 1903 February, pp. 306–14. (ISSN 2043-5290)

1904: The Work of Queens’ College in Peckham, by the Rev. J. W. Maunders, in The Cambridge Mission to South London : a twenty years’ survey, eds. Andrew Amos and William Woodcock Hough, pp. 113–20. (OCLC 23667962)

1905: Bibliography of College, Social, University and Church Settlements, by Caroline L. Montgomery (née Williamson), 5th Edition, pp. 106, 114. (OCLC 3218348)

1910: Queens’ College Boys Club, in Cambridge in South London : being a brief account of the work undertaken in South London by the University and certain of the colleges. (OCLC 55866258)

1911: The Mission, in The Dial, No. 10, 1911 March, pp. 61–4. [Problems at Peckham; the move to Rotherhithe]

1914: The Queens’ College Mission Rotherhithe, by the Rev. J. Kingdon, in Cambridge in South London : the work of the College Missions, 1883–1914, ed. Norman Braund Kent, pp. 187–90. (OCLC 36420056)

1934: The Status of Queens’ House. [Report to Governing Body, 1934 February]

1939: The Future of Queens’ House Rotherhithe. [College open meeting paper]

1949: The evidence for voluntary action, by William Henry Beveridge and A.F. Wells, p. 129. (OCLC 1285683)

1964: Where the L.C.C. Plan to Build a Garden: An 18th Century Thameside Terrace in the Pool of London, in Illustrated London News, No. 6502, 1964 March 14, p. 395. (ISSN 0019-2422) [Drawing of Queens’ House Rotherhithe shortly before demolition]

1976: College missions and settlements in South London 1870–1920, by James Graham Wallace Dickie (OCLC 863533391) [Oxford B.Litt. thesis]

1987: A History of Queens’ College, Cambridge, 1448–1986, by John Twigg, pp. 280–2, 353. (ISBN 978-0-85115-488-6)

1989: Queens’ House 1941–53, in By Peaceful Means : The Story of Time and Talents 1887–1987, by Marjorie Daunt, pp. 39–42. (ISBN 978-0-9515227-0-7)

2007: Squires in the slums : settlements and missions in late-Victorian London, by Nigel Scotland. (ISBN 978-1-84511-336-0)