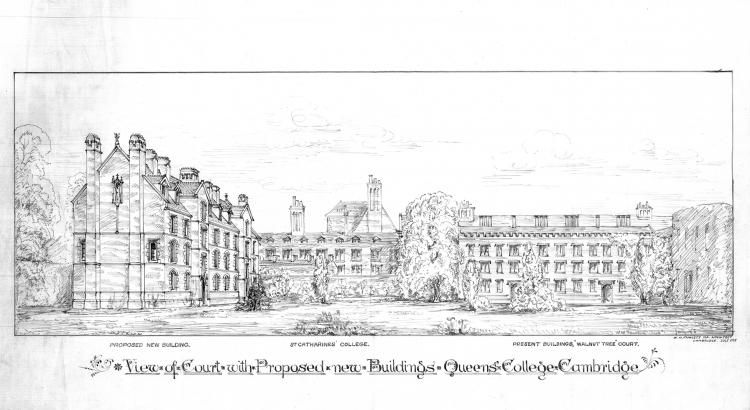

Friars’ Building was built in the neo-Gothic style, using red brick and stone relief, and was intended to reflect the style of the 1448 buildings of Old Court, which at that time it faced, before the new Chapel was built in-between.

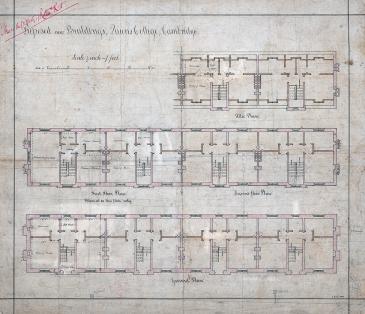

Friars’ Building had four staircases (M, N, O, P), each of four storeys, each storey (as originally constructed) having two sets, making 32 sets in all. Each set had a living room facing south looking over the court, and a bedroom looking north towards King’s College, with a small lobby leading from the staircase landing.

Friars’ Building had four staircases (M, N, O, P), each of four storeys, each storey (as originally constructed) having two sets, making 32 sets in all. Each set had a living room facing south looking over the court, and a bedroom looking north towards King’s College, with a small lobby leading from the staircase landing.

The contract drawing shows that one set, on the first floor of staircase M, was intended for a Fellow.

Critical reception

Queens’ … has a building of red brick at right angles to the river, which must ever be an eyesore to lovers of the backs. The best thing that can be hoped for it is that it may be snugly wrapped in creepers, but even this will never destroy its prime fault, its want of proportion that must ever remain to offend. … Are colleges so poor and sites so dear that all their buildings must be four storeys high? It needs a power of length and breadth too for the matter of that to carry off four storeys.

[The Cambridge Review, Vol. XI, 1889 Nov 7, p. 52]

The view which so offended that critic was blocked by the erection of Erasmus Building in 1959.

Subsequent history

At some early point in the building’s history, a bath and WC were squeezed into a former gyp-room on the attic storey of each staircase: one room to be shared by everyone on that staircase. Prior to that, the only facilities were external earth-closets.

At some early point in the building’s history, a bath and WC were squeezed into a former gyp-room on the attic storey of each staircase: one room to be shared by everyone on that staircase. Prior to that, the only facilities were external earth-closets.

In the early 1950s, the ground, first, and second floors were altered: each set was subdivided into two study-bedrooms, so as to increase the capacity of the building to 56. In each former set, the entry lobby was removed, and the dividing wall was moved southward so as to increase the size of the former bedroom. Both new rooms were given doors direct to the landing, and equipped with fitted furniture, including a hand wash-basin. These works were carried out at a time of post-war rationing of building materials.

In 1980, one study-bedroom on the ground floor of each staircase was converted to showers, WCs & baths, to the design of Julian Bland, architect. The building now accommodates 52 students.

Between 2003 and 2007, all the gyp-rooms were modernised and refitted. The formerly solid gyp-room doors were fitted with glass panels, and all bedroom doors had their fire rating upgraded.

In 2010, the building was re-roofed, with associated fabric repairs, thermal insulation, and lightning protection.

In 2013, secondary glazing was fitted to the windows of every residential room.

Background

The court and building are called Friars’ because they are on the site of a former Carmelite monastery, later suppressed by King Henry VIII. Queens’ acquired this land in 1544 (from the President Dr Mey who had bought it in 1541), and by 1545 made it into a second garden for the President. It connected to his first garden by a curious little yard with four doors, which permitted the President to pass diagonally between his two gardens, and the Fellows to pass diagonally between Walnut Tree Court and their garden (now the lawn under Erasmus Building), without either trespassing on each other’s territory: for the President was not a Fellow, and could not enter the Fellows’ Garden, and the Fellows could not enter either of the President’s Gardens.

The north wall of the former chapel of the Carmelite monastery forms part of the boundary wall between Queens’ and King’s Colleges. On the Queens’ side, it is largely hidden by workshops. It is entirely possible that this wall is the oldest building in College. The Carmelites buried their dead in and around their chapel, and human remains were discovered during the erection of Friars’, Dokett and Erasmus buildings. According to the recollections of someone who was a boy at the time of the digging of the foundations for Friars’:

During the excavations, thirteen skeletons, plus a horse’s skull, were dug up …

[Some Memories of Old Queens’, by Harold Temperley, in The Dial, No. 89 Easter 1938, pp. 5–9 at p. 6]

Alternatives unbuilt

Before the final design was selected, a number of alternates were considered, including this design having only two staircases with double the number of sets per landing.

Before the final design was selected, a number of alternates were considered, including this design having only two staircases with double the number of sets per landing.

Further reading

1886: The Architectural History of the University of Cambridge, by Robert Willis and John Willis Clark, Vol. 2, pp. 770–1. (OCLC 6104300)

1899: The Queens’ College of St Margaret and St Bernard in the University of Cambridge, by Joseph Henry Gray, p. 288; (OCLC 8568413)

1926: New edition, updated, p. 264. (OCLC 79562186)

1951: A Pictorial History of the Queen’s College of Saint Margaret and Saint Bernard, commonly called Queens’ College Cambridge, 1448–1948, by Archibald Douglas Browne (1889–1977) & Charles Theodore Seltman, plate 117. (OCLC 7790464)